I’ve written previously about how the truck industry is fighting regulations at the state and federal level with everything they’ve got. One of the scare tactics truck manufacturers have been pushing is the old industry canard of job-killing regulations. To tackle this topic head-on, UCS, together with the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Sierra Club, commissioned a study of the impacts of truck regulations on employment from Environmental Resources Management (ERM), an independent consultant.

Unsurprisingly given the industry’s history, ERM’s analysis shows that the studies being touted by truck manufacturers do not support their claims, and that more careful and rigorous analysis shows that EPA’s previous truck regulations did not in fact result in any adverse impacts on truck manufacturing employment. This pushback is critical as industry continues to fearmonger about EPA’s current proposal.

Why would truck regulations impact jobs?

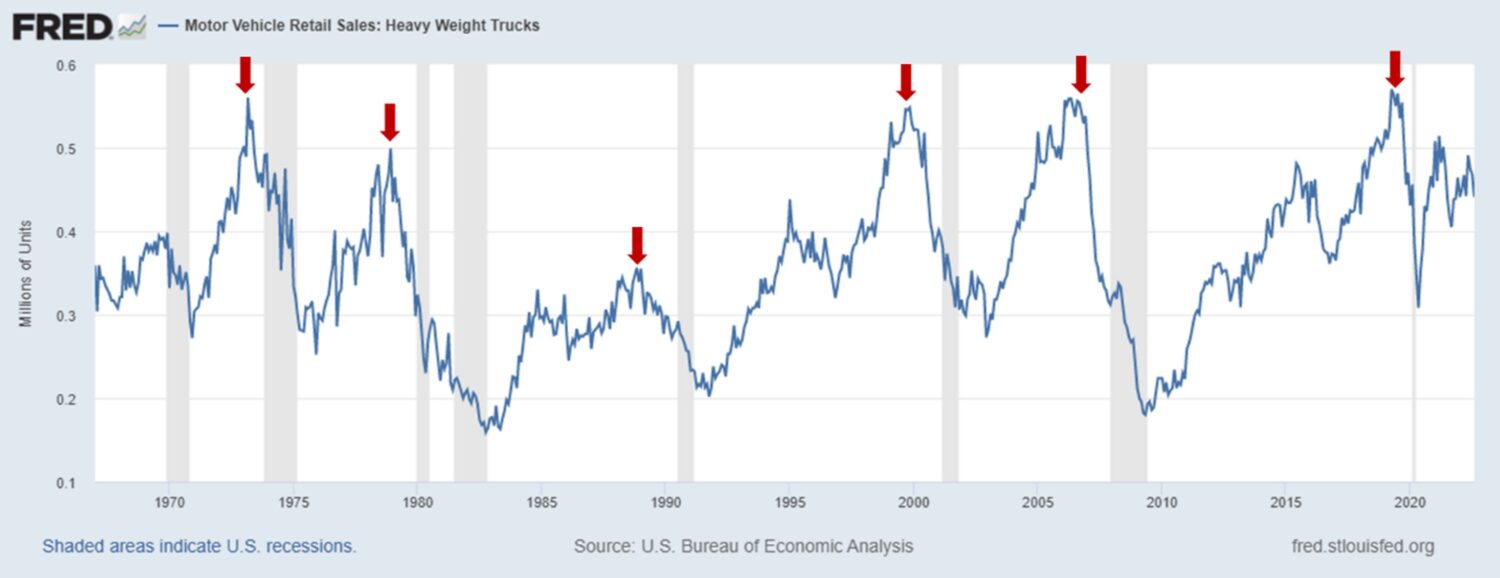

Before diving into the conclusions of the report, I think it’s important to describe what industry is erroneously claiming. The theory being put forward by industry is this: diesel emissions regulations require the adoption of new technology at high cost; because of that high cost, truck fleets are going to avoid purchasing new trucks; in order to do this, they will pull forward truck purchases, buying new trucks in advance of the regulation; ergo, this will lead to a surge in trucks ahead of the regulation going into effect (pre-buy), and an ensuing decrease in purchases after the regulation because fewer new trucks will be needed (low-buy). It is then assumed that this pre-buy/low-buy effect will lead to commensurate impacts on jobs proportionate to sales.

While this complicated chain of events being proffered by industry may sound possible, the data simply do not bear it out.

Industry can’t even agree with itself about this effect

There have already been a few studies looking for evidence of a pre-buy/low-buy effect. Primarily, these have focused on the 2007 EPA regulations, which were the first step in the phase-in of diesel engine standards meant to cut particulate emissions by more than 80 percent and smog-forming nitrogen oxides (NOX) emissions by 90 percent. Though manufacturers largely didn’t adopt the necessary emissions control technology to meet the NOX requirement until 2010, the 2007 standard did require new technologies to be deployed, at an increased upfront cost.

At least four separate studies took a look at whether or not there was an observable pre-buy. Importantly, none of them could agree on when the pre-buy occurred, its magnitude, and some didn’t even bother to try to look at whether there was a corresponding low-buy period. Unsurprisingly, the manufacturer-funded studies claimed far higher impacts on sales. But during the period which industry claimed saw a decrease in sales, academic research found instead an increase in sales. So what gives?

Given the widely varying results from four studies claiming to measure the same thing, it casts a huge amount of doubt on the validity of their respective results.

More robust and rigorous results show no pre-buy effect

The studies considered above used linear-regression models focused solely on truck sales data. One problem with such an approach is that it inherently assumes that the researchers have adequately taken into consideration all the possible factors that could affect those sales absent the regulation. A more rigorous approach to such analysis is to use a “difference-in-difference” model, which uses a related set of data that did not undergo a similar policy intervention to help capture the expected industry-wide behavior over the same period.

In identifying a “control group” for trucks, there are a few different approaches – one can compare heavy-duty trucks to light-duty vehicles, which did not undergo the same change in regulations, or one can even directly compare data of different classes. By identifying an appropriate control group, it ensures that any such impacts are more likely to be related to the actual policy intervention of interest.

In addition to considering multiple control groups to limit the noise, ERM considered different time periods for the pre-buy/low-buy effect to have occurred over. And, most importantly, unlike the other studies, in addition to sales and production data, ERM thoroughly examined the impact on employment.

Based on this wealth of data and analysis, ERM came to a clear conclusion:

The results of this study demonstrate that there is no material impact of the 2004, 2010, 2007, and 2014 HDV emission regulations on industry employment. Moreover, our results and the lack of consistent results from other studies indicate that there is also no firm basis for concluding that there is a material pre-buy/low-buy impact on sales or production as a result of HDV engine regulations.

<mic drop>

So, is industry just full of it?

Given the compelling results of the ERM study, it does beg the question: is this just another example of industry pay-for-play? It’s easy to say “Yes, absolutely,” since the truck industry commissioned the study from an organization (ACT Research) that is on the record pre-judging the outcome of the 2004 and 2007 regulations—they knew the answer that ACT Research was going to give because they’d already made the claims well in advance of the “study” (see also, e.g., Senior ACT researcher Ken Vieth’s diatribe in response to an unrelated NHTSA peer review process, which doesn’t even attempt to consider broader macroeconomic details).

However, given that there have been claims of a pre-buy even from non-industry sources, it’s worth considering why folks are getting it wrong. Apart from industry trying to extrapolate too much from anecdotal evidence, the most significant explanation for what happened with regards to 2007 sales and production data is that truck sales tend to be an early indicator of a recession. This makes sense—companies will constrain spending when the market tightens and economic outlook begins to dim, things which tend to happen well in advance of the economy moving into a recession.

In this particular case, the drop in 2007 sales is not related to a low-buy effect but is instead likely reflective of the conditions that led to the recession the following year. The effect in sales was particularly noticeable because of a surge in demand for trucks left over from a prior credit crunch in the early-2000s that led to an abnormally old truck fleet.

Will the lack of evidence supporting a pre-buy encourage EPA to set stronger standards?

One of industry’s biggest talking points being proven bunk means EPA must not project any such purported jobs impacts in its analysis. And stakeholders and policymakers who took a stance against strong regulations in large part due to the scaremongering claiming there would be such impacts should obviously rethink that position and vocally align with the immense political support for strong diesel truck emissions standards.

It’s not clear whether such late-breaking support will be enough. Industry has spent years pushing for weaker regulations and continues to advocate for the worst possible outcome for the communities inundated by freight pollution. There’s just two months remaining before EPA must finalize its rules—we hope that EPA will follow the strongest available evidence over truck manufacturers’ lobbying.