Last week, I testified at a public hearing to press the Biden administration on new vehicle standards that have the potential to significantly cut oil use. While the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)has drawn all the attention lately for its spring proposals to cut emissions from new vehicles by electrifying both passenger cars and heavy trucks, the o.g. leader in cleaning up the light duty fleet quietly released its own proposal in August: the Department of Transportation’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) has proposed to improve fuel economy of passenger cars and trucks steadily from 2027 through 2032 and heavy-duty pickups and vans from 2030 to 2035.

While it might seem strange to some that two different government agencies are releasing new rules at the same time for the same set of vehicles, below I explain the importance of both programs and why we need NHTSA to do better.

A brief history of fuel economy standards

In the wake of the 1970s oil embargo that resulted in gasoline shortages and rationing, the country started to recognize the harm of a daily life reliant upon oil. In response, Congress put in place regulations to cut oil use from new passenger vehicles, known as the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) program. Established in 1975, these rules require that the vehicles a manufacturer sells in a given model year must meet an annual target.

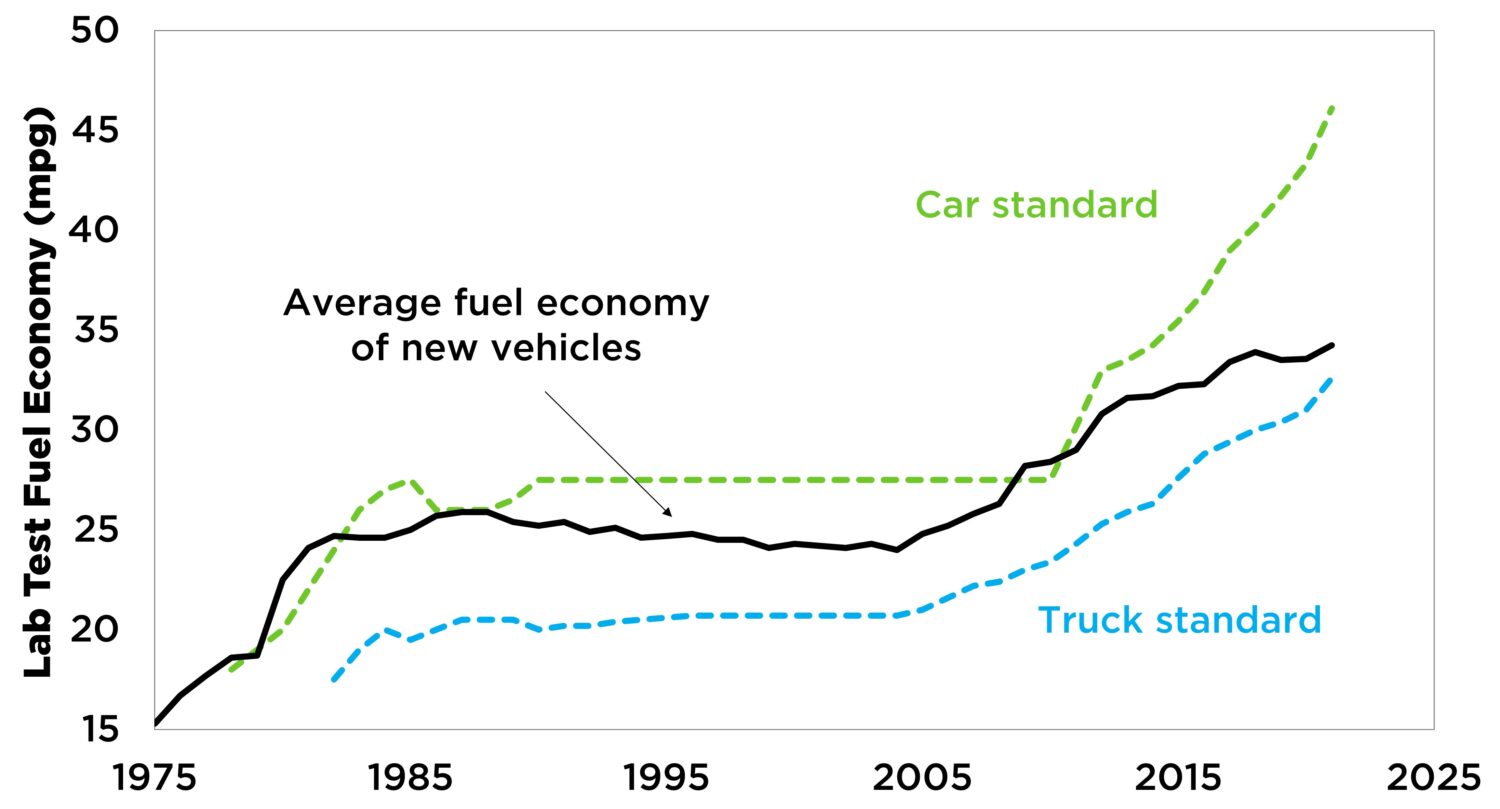

In the first years of the CAFE program, new vehicle fuel economy rocketed upwards, improving on-road fuel economy for new cars and trucks from 13 miles per gallon (mpg) to 21 mpg in less than a decade. However, with the oil crisis in the rear-view mirror, then-President Ronald Reagan acceded to requests from Ford and General Motors to reduce fuel economy standards for a few years, and the political will to strengthen the program petered out. For about two decades, not only did progress on fuel economy stall, but growth in SUV sales in the 1990s caused the fuel economy of passenger vehicles, on average, to get worse year after year.

By the 2000s, a Congressional hold on funding preventing work on fuel economy standards finally broke, and NHTSA staged the first increase in fuel economy in over two decades, requiring the SUVs and pickups that had exploded in sales to finally use less fuel. Shortly thereafter, the Supreme Court ruled that EPA had the authority to regulate carbon dioxide emissions from passenger cars and trucks under Massachusetts v. EPA, and Congress finalized the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007, requiring increasing fuel economy standards. Since then, EPA and NHTSA have jointly set standards to improve fuel economy and reduce emissions from new vehicles through a series of rules that, together, are the single biggest program the United States has implemented to cut petroleum use and heat-trapping emissions.

Differences between setting fuel economy and emissions standards

Under the Clean Air Act, EPA is obligated to reduce pollution from mobile sources like passenger cars and trucks when those emissions are a risk to public health and/or welfare. As such, the agency has set emissions standards for particulate matter (soot, or PM), smog-forming emissions like nitrogen oxides (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and heat-trapping emissions like carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) commonly found in air-conditioning systems.

While reducing some of that pollution can be done by improving the efficiency of internal combustion engines, EPA’s mandate is not focused on efficiency but on protection from the harm of such pollution. As such, under the Clean Air Act EPA has a strong incentive to push the market to adopt advanced technologies like electric vehicles, which can eliminate tailpipe pollution entirely.

On the other hand, NHTSA’s mandate is to cut petroleum use, which puts the focus on alternative fuels to gasoline. At one point, Congress required the agency to heavily incentivize the adoption of ethanol as a fuel by encouraging manufacturers to produce vehicles that could be fueled by either gasoline or ethanol (so-called flex-fuel vehicles). Additionally, there are incentives for natural gas vehicles and electric vehicles. However, electric vehicles are incentivized not by looking at the amount of oil usage (which is essentially zero, since only Hawaii and Alaska have any substantial share of electricity generated by petroleum), but by consideration of energy usage in total, helping to drive efficiency improvements from EVs as well.

In addition to differences in their statutory authority, there are differences in the designs of the CAFE and EPA programs. For example, under NHTSA, there are separate standards for domestically produced passenger cars, imported passenger cars, and light trucks, with limits on how many credits from overcompliance from one fleet can offset another. No such limits exist for EPA. The effect of this is that under CAFE, manufacturers have to invest more evenly in reducing fuel use from both cars and light trucks. Another difference is that while Congress authorized incentives for alternative fuels, they prevented NHTSA from requiring their adoption in setting their standards.

How fuel economy and emissions standards work together

Under the Obama administration, the EPA and NHTSA programs were largely drawing upon the same set of technologies to simultaneously cut petroleum use and heat-trapping emissions. However, with electrification set to take off, differences in the design of the two programs are causing some consternation for manufacturers. But in my opinion, that’s exactly the point—we need automakers to be able to walk and chew gum at the same time.

These rules have different objectives and work together to clean up the automotive sector. In the long run, we need to move towards a fully electric future, eliminating tailpipe emissions and cutting overall emissions as we continue to clean up the electric grid. In the short term, however, we need to be making sure that the remaining internal combustion engine fleet uses as little fossil fuel as possible. It is not enough to invest in the future—we need automakers to make good on the technology opportunities already available today to cut fuel use.

Because EPA ignores emissions from the electric grid in setting its standards, this creates a strong incentive for manufacturers to grow EV sales: increasing EV sales by 5 percent is worth the same amount of credit as improving gasoline vehicles by 5 percent. But this means once a company is targeting 40 or 50 percent EV sales, it makes it much more likely that they’ll just bump those sales up slightly rather than improve the shrinking share of their fleet powered by gasoline.

On the other hand, NHTSA doesn’t incentivize EVs so heavily. This means even as EV sales take off, there’s still a strong incentive to improve the remaining gasoline-powered fleet. And if we are to address our fossil fuel dependence ASAP, we need to be targeting both near-term and long-term reductions. We can’t let automakers make big EV promises and continue to sell boatloads of inefficient SUVs that will be on our roads guzzling gasoline for the next 30 years.

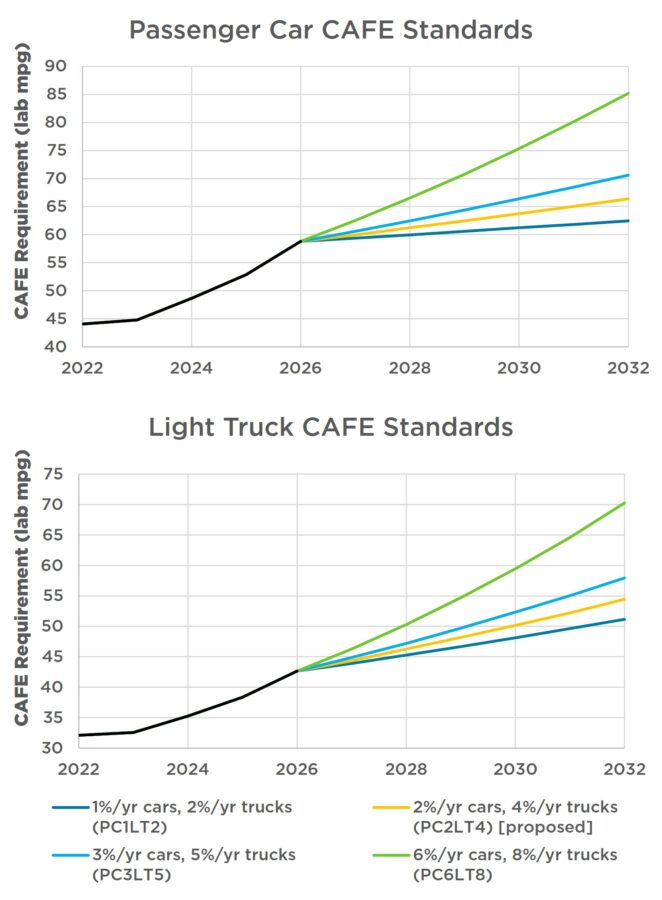

What NHTSA is proposing

NHTSA is proposing to improve fuel economy by 2 percent per year for passenger cars sold in 2027-2032 and 4 percent per year for light trucks. However, this falls short of what can be accomplished in this time frame. It also risks extending some of the loopholes that EPA is trying to close under its greenhouse gas program. For example, off-cycle credits designed to incentivize technologies whose benefits aren’t captured by conventional lab tests have been shown to award manufacturers more credit for reductions than such technologies yield in the real world—while EPA is proposing to phase out these credits, NHTSA is not.

Similarly, EPA has proposed altering the attribute curves by which the standards are determined—bigger cars and trucks have to meet lower fuel economy and higher emissions targets because (purely from a physics perspective) it requires more energy to move such vehicles for comparable technologies. Unfortunately, this has created an incentive for manufacturers to increase the average size of their fleet, something which EPA is now proposing to address. NHTSA has not proposed a comparable approach, which could perpetuate the truckification of the passenger vehicle fleet.

Any such loopholes will be used by manufacturers to undermine the effectiveness of any fuel economy rule, and NHTSA needs to put the brakes on such approaches.

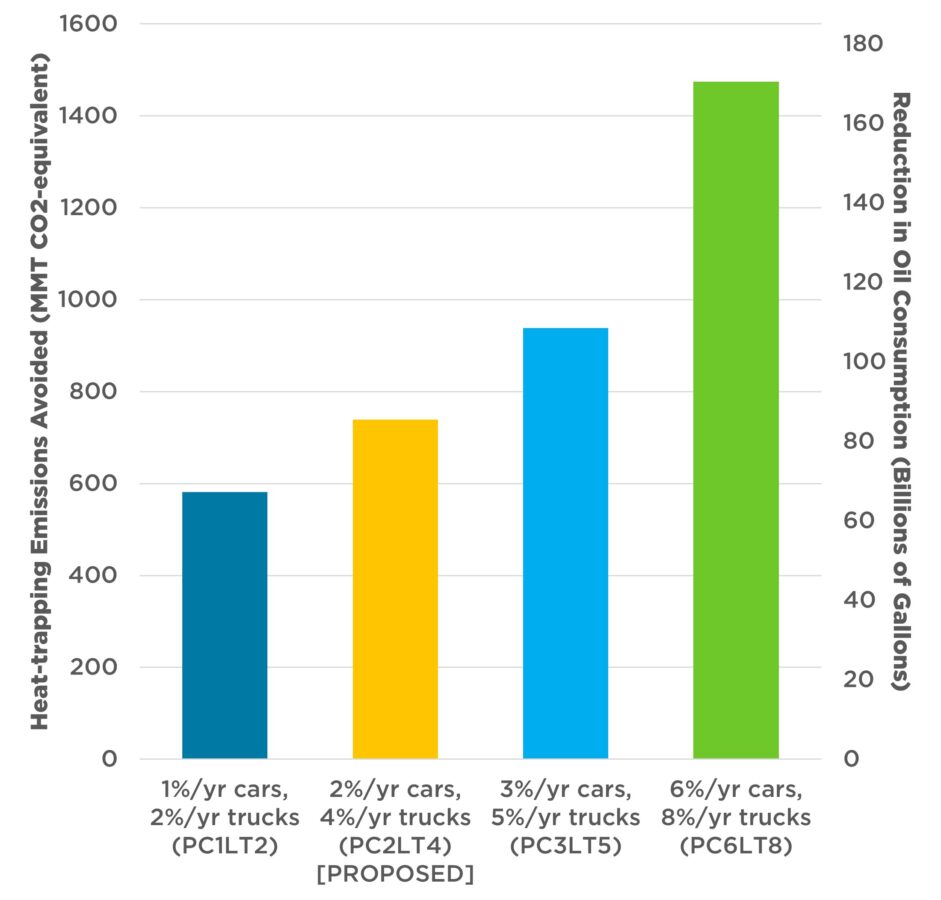

In addition to the preferred alternative (called PC2LT4 for requiring 2 percent and 4 percent per year improvement), NHTSA is requesting comment on additional alternatives. The most stringent alternative is PC6LT8, which is comparable to EPA’s Alternative 1, which we argued the agency should adopt. However, owing to NHTSA’s statutory limitations, it may not be possible for the agency to finalize such a stringent rule. We do know, however, that the next most stringent alternative is easily achievable, so UCS is pushing the agency to finalize a rule that is at least as strong as its PC3LT5 option, while also closing some of the loopholes mentioned above.

What is at stake

If NHTSA’s CAFE program is too weak, there will be little pressure on manufacturers to improve the efficiency of their remaining gasoline-powered fleet. While UCS is targeting electrifying the entire new vehicle fleet by 2035, around half the cars we sell between now and then will have a combustion engine—that’s over 100 million more gasoline-powered cars and trucks. We’ve got to keep our foot on the accelerator to reduce emissions from those vehicles as we shift to electric vehicles.

Compared to NHTSA’s preferred alternative, the next most stringent standard (PC3LT5) would cut gasoline use and heat-trapping emissions 27 percent more from vehicles sold through the 2032 model year. And if NHTSA were to finalize a rule consistent with its strongest alternative, it would double the reductions from its proposal. This translates to at least $12 billion back in the hands of consumers (PC3LT5) and up to $36 billion (PC6LT8) that could be put to better use in our economy, thanks to the deployment of technology that would cut oil use by up to 170 billion gallons compared to the status quo.

We need NHTSA to drive improvements across the light-duty vehicle fleet, particularly from gasoline vehicles. UCS will be making the strongest case we can for efficiency improvements as we target a cleaner transportation future—if you, too, want to add your voice to the chorus, you can let NHTSA know what you think of its proposals.

Methodological note: The numbers in this blog are an estimate using NHTSA’s own modeling tool and assumptions, except that it is assumed manufacturers will not apply new technology in the absence of improved standards. Even greater benefits are likely possible after taking into account other shortcomings in the agency’s analysis, which we will continue to point out in our full written technical comments to be submitted in the coming weeks.