Any day now, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is slated to propose its first regulation on stronger criteria pollution controls for heavy-duty trucks in over 20 years. However, the agency is currently under extreme pressure from industry to propose an absurdly ineffective standard and some parts of the industry are even questioning whether EPA should set a new standard at all.. Below, I discuss the ways in which this is just a continuation of a long history of industry malfeasance, as we look for EPA to remain steadfast and propose strong standards for the sake of public health.

A history of playing dirty

It’s worth emphasizing that this is not the first time that diesel truck manufacturers have driven to pollute more—in fact, the most current regulations on the books are the result, in part, of these same manufacturers previously getting caught back in the 1990s with defeat devices that cheated emissions tests in order to pollute more in the real-world (akin to the more recent VW Dieselgate). Not only did this result in the industry having to meet new regulations 2 years earlier (in 2002, instead of 2004) as well as introduce new test procedures designed to circumvent the manufacturers’ cheating to ensure that trucks were reducing emissions in the real world, but the resulting $1 billion settlement helped fund emissions controls research supporting the further 90 percent reduction in smog-forming nitrogen oxide (NOx) and particulate emissions required by 2010.

A skirmish at the state level

EPA’s revolutionary truck emissions standards finalized over 20 years ago facilitated the development and adoption of selective catalytic reduction, and the concurrent introduction of low-sulfur diesel fuel that helped make these new emissions controls viable. As a result, truck emissions have dropped significantly. However, a large body of evidence, including data supplied by manufacturers to EPA, shows that there were unanticipated gaps in the regulation that mean real-world improvements are not as robust as initially intended across all types of operating conditions, including those most likely to be found in highly trafficked areas like ports and commercial districts where communities are heavily burdened by truck pollution.

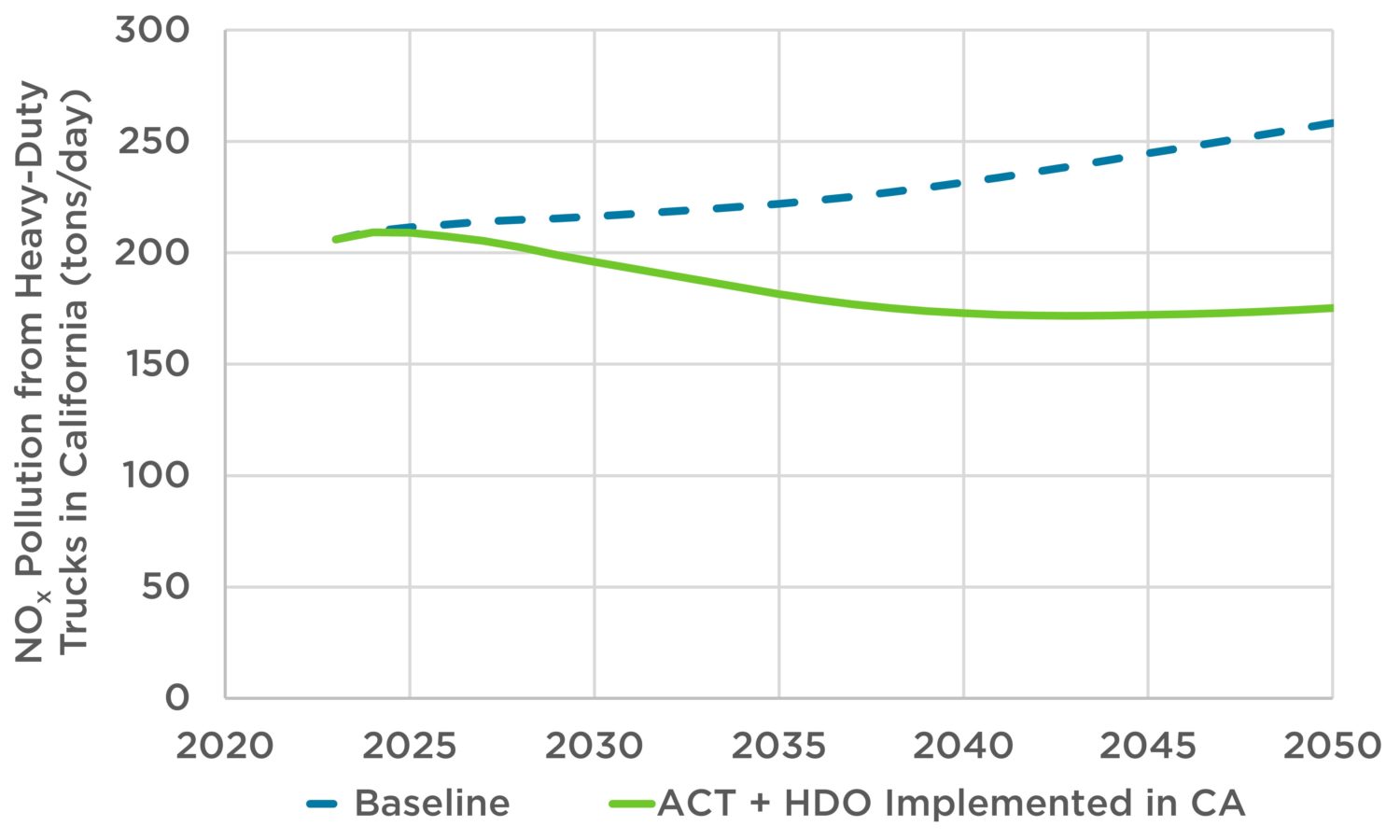

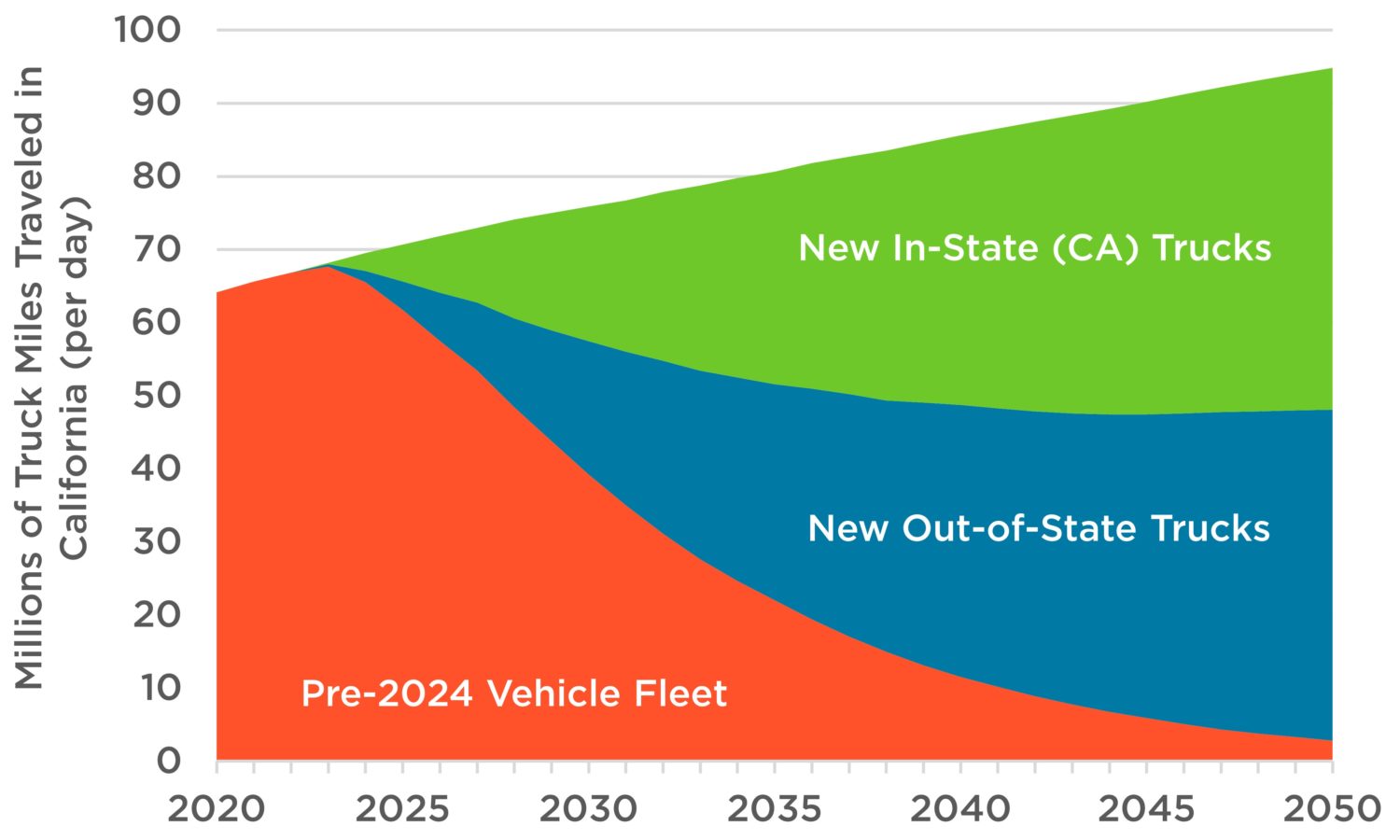

With EPA deciding not to take earlier action despite lingering concerns around air quality, the State of California moved forward with its own package of regulations to further reduce emissions from heavy-duty trucks. The first is the Advanced Clean Trucks (ACT) rule, which requires an increasing percentage of vehicles sold in the state be electric. The second was the Heavy-Duty Omnibus (HDO) rule, which looked to not only reduce smog-forming NOx emissions from trucks on lab tests but also increase requirements on warranty and real-world emissions to ensure that trucks maintain these lower emissions over their entire lifetime on the road. In order to address the remaining truck pollution in the state, California is moving ahead to accelerate the adoption of the cleanest technologies available through a third regulation, the Advanced Clean Fleet rule.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, truck manufacturers took umbrage with the state’s efforts and pulled out all the stops, including threatening not to sell trucks in the state, self-referentially claiming surveys of its own members as “data” on wildly inflated warranty costs, and even calling upon then-President Trump to set national regulations to try to supercede California’s efforts.

Truck manufacturers run the disinformation playbook

Sadly, this war on stronger regulation did not end with the eventual passage of California’s strong regulatory package. In fact, if anything, it appears to have made the truck manufacturers more determined to undermine every additional regulatory action by pulling out every page in the Disinformation Playbook. Research on industry disinformation shows how companies manipulate the regulatory process for their own gain, and we’re clearly seeing that today from the trucking industry.

On the state front, they’ve manufactured uncertainty about the science by putting the same bad data in front of regulators in Oregon, New Jersey, Washington, and more, while also lying about the regulatory timeline in an effort to confuse and stave off further regulation of truck pollution in those states. Thankfully, this is a battle the industry is losing.

On the federal front, the industry has put together some monstrously bad disinformation for hire. For instance, the Truck Dealers Association submitted a report on the impact regulations have on jobs, but the report is so faulty and out of date that it ignored the impact of the Great Recession on the time period in question (2008-2012). The manufacturers submitted their own pay-for-play garbage analysis, with both a health study that ignored EPA’s real-world emissions data to underestimate benefits and another that ignored the cost of extended warranties currently borne by their customers in order to inflate costs.

They’ve also tried to manipulate government officials by having their bigwigs try to sway political leaders behind closed doors. Truck manufacturing CEOs held a roundtable with EPA Administrator Michael Regan back in August and met again with him twice before the rule his agency is considering went into its review, once at a trucking conference in Nashville in October and again at Volvo’s facilities in December. They’ve also engaged in high-level White House meetings, including National Climate Advisor Gina McCarthy and White House economic advisor Brian Deese, in an effort to sway the political machine to write a weaker rule. While some stakeholder engagement is normal, the frequency of these meetings and stature of the parties involved is atypical enough to raise eyebrows, catching the attention of the press.

Is EPA going to fumble?

We at the Union of Concerned Scientists (and many other NGOs) have been trying to run our own playbook to counter this colossal industry effort, relying on reams of evidence as we seek regulations that are at least as protective as what California already passed in its 5-year, data-driven process. But at the same time, we know how successful industry’s tactics have been, historically—and communities disenfranchised by our political processes have been bearing the brunt of the costs of our systemic inaction for decades.

The questions we have now, as we prepare for EPA’s proposal to finally deal with the problem of truck pollution and put us on a path towards eliminating it entirely—is industry’s war to pollute going to win the day, with EPA fumbling this critical opportunity? Or is the Biden administration going to make good on its promises to focus on the needs of the communities unjustly burdened by truck pollution?

Regardless, we at UCS are preparing to bombard them with cold, hard data to pressure them to set the strongest standards possible and put us on a path to eliminate diesel truck pollution entirely.