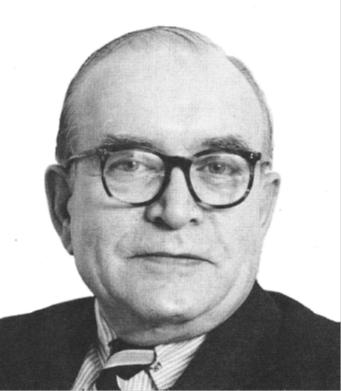

The arms control community lost one of its true heroes recently with the passing of Ambassador Jonathan Dean. My colleagues and I at UCS remember him especially fondly.

After retiring from a long career in the U.S. Foreign Service, Jonathan came to UCS at age 60—with no thought of slowing down—so he could continue to work on the issues that motivated him throughout his life. He spent more than 20 years here, bringing the same commitment to peace, and the tireless and patient approach to his work, that he showed during his government career.

After retiring from a long career in the U.S. Foreign Service, Jonathan came to UCS at age 60—with no thought of slowing down—so he could continue to work on the issues that motivated him throughout his life. He spent more than 20 years here, bringing the same commitment to peace, and the tireless and patient approach to his work, that he showed during his government career.

Jonathan’s interest in the security field was in no way theoretical. He was a wiz-kid—he started at Harvard at age 16—but dropped out the next year after the bombing of Pearl Harbor to join the army. That entailed going to Canada since joining the U.S. army at his age required permission from his parents, who were dead set against his plan. In June 1944, he landed at Normandy with Canadian forces two days after the initial U.S. D-Day landing. His chin carried a scar from a bullet wound he received later in the war. In the early 1960s, after joining the State Department, he served in the Congo at a time of turmoil at significant personal risk.

I was fortunate to have spent more than a decade working as a colleague of Jonathan’s at UCS. We have posted a detailed obituary here. But a few more personal recollections stick out in my mind.

First, Jonathan was one of the least cynical people I’ve ever known—despite his being a very acute observer of the real world. Over the years I’ve found that to be especially rare in Washington. He seemed to accept the frustrations and slow progress inherent in trying to advance arms control, including slogging through eight years as the negotiator of the unsuccessful U.S.-Soviet talks to limit conventional forces in Europe (the Mutual and Balanced Force Reduction talks). But he saw this work eventually bear fruit when the follow-on talks—the Conventional Forces in Europe (CFE) Treaty—ended up cutting conventional forces far beyond what anyone imagined possible.

The second thing I remember is that he never seemed to be discouraged. He would craft policy proposals, patiently explain them, and carefully listen to the responses. Based on that he would re-craft his proposals and start the cycle again. He knew that part of the battle was educating people and supplying them with motivation and good ideas, and that part of it was outlasting people or situations that were barriers to progress.

The third thing is that Jonathan would engage—respectfully—with anyone who was serious about grappling with the issues he cared about, regardless of where they were on the policy or political spectrum. He had friends in DC who were much more conservative than he was. I also remember on several occasions that he flew to Germany to address German peace groups that were considered too “fringe” by most policy-types to be taken seriously. He was for years an advisor to and collaborator with Randy Forsberg, who started the Nuclear Freeze movement.

Jonathan was one of the most decent and committed people I’ve met. He was a remarkable man and a true inspiration.