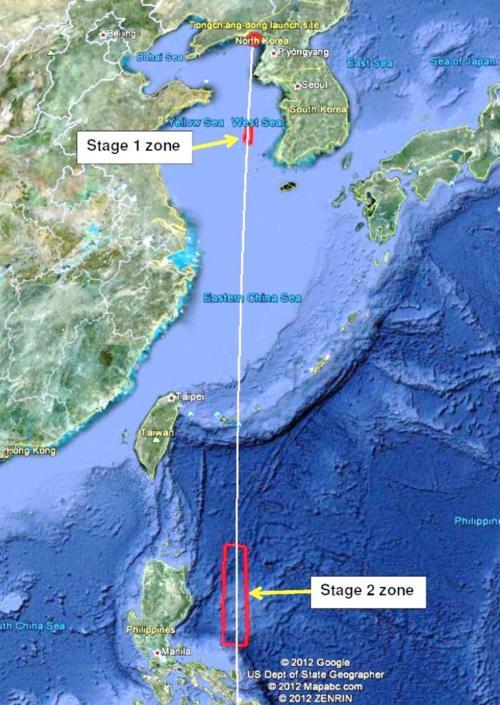

As it did before its April 2009 launch, North Korea has announced the zones where it expects the first two stages of its launcher to splash down, to warn shipping and air flights in those regions. The documents were just made public, but are dated March 16.

The announcement said the launch would take place between 7 am and noon local time in North Korea between April 12 and 16; that corresponds to 6 to 11 pm EDT on April 11 to 15 in the U.S.

The location of these zones verified that, unlike the April 2009 launch, the Unha-3 vehicle will use the new Tongch’ang-dong launch site and will launch south rather than flying east over Japan. North Korea announced two splashdown zones, which is consistent with a 3-stage rocket since the final stage has a speed very similar to the satellite it releases and will stay in orbit if the launch is successful.

The splashdown zones lie close to South Korea and the Philippines, and it will be interesting to see the reaction of those countries to the announcement.

The distances of the splashdown zones from the launch site is different than those in the 2009 launch. In particular, the splashdown zone for the first stage is centered at a distance of about 450 km from the launch site and is about 80 km long and 30 km wide. In the 2009 launch, that zone was centered about 625 km from the launch site and was about 250 km long and 20 km wide.

The splashdown zone for the second stage is centered at a distance of about 2,500 km from the launch site, and is about 475 km long and 100 km wide. In the 2009 launch, that zone was centered about 3,600 km from the launch site and was 800 km long and 150 km wide.

While the 2009 launch gained some speed compared to this launch from the rotation of the earth due to its eastward launch, that is not enough to account for these differences in splashdown ranges. North Korea needed to change the location of the second-stage zone to avoid landing on the Philippines.

This difference in the distances of the splashdown zones from the launch site may reflect some changes in the launcher. In order to place a satellite in orbit without being launched eastward, the Unh-3 itself will have to accelerate to a speed about 4% higher than the Unha-2 used in the 2009 launch. North Korea may attempt to get that additional velocity increase from the third stage by increasing the mass of fuel it carries. If so, that could reduce the burnout speeds of the first two stages, which would cause them to fall at shorter ranges. Modeling the launch should shed light on this.

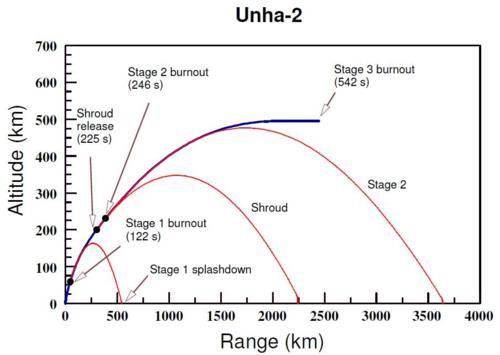

Below is a diagram showing a reconstruction of the April 2009 launch based on our modeling of the Unha-2 missile, which may be useful for people who haven’t thought about the relation of the splashdown locations to the launcher’s trajectory. The blue curve shows the trajectory of the stages of the launcher that are still powered. Once the first stage burns out and is dropped (at 122 seconds), it follows a ballistic path (shown in red) and splashes down around 550 km from the launch site. A similar thing happens when the shroud covering the satellite is released (at 225 seconds) and the second stage burns out (at 246 seconds). Those splashdown points depend on the speed and angle of the trajectory at each of those times, and must also be consistent with what else is known about the launcher, such as the thrust of each stage.

For the 2009 launch, the third stage did not ignite and that stage and the satellite followed the red path of stage 2 into the ocean. Had the third stage worked as expected, it might have followed the blue path until 542 seconds, at which point it would have released the satellite into orbit.

Previous post on North Korea. Next post.