This is the first of 3 posts on spent fuel safety.

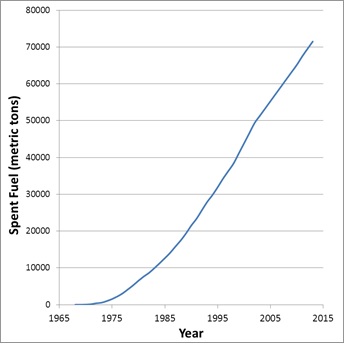

In case you don’t have enough to worry about, consider this: nuclear reactor waste is piling up at U.S. reactor sites.

Because the U.S. has not opened a repository to store reactor waste, the government has not fulfilled its promise to take spent fuel from nuclear plants and dispose of it. As a result, spent nuclear fuel has accumulated at the reactor sites, reaching a level of 70,000 metric tons today. And over 70% of that waste is stored in increasingly crowded cooling pools that were originally intended to hold much less fuel.

A key step to increase the current safety of U.S. nuclear power is to transfer a large amount of the spent fuel from pools into concrete “dry casks” that would be stored temporarily at the plant. Since spent nuclear fuel is cool enough to transfer to dry casks after 5 years, more than 80% of spent fuel currently in pools could be moved to dry casks.

Pool accidents could be disastrous

Nuclear fuel typically stays in the core of a reactor generating energy for several years. When they are taken out of the core the fuel rods are highly radioactive and continue to generate lots of heat. They are moved into a cooling pool at the reactor site, where the water acts as a radiation shield and carries the heat away from the rods. The water must be continuously cooled, which requires electric power.

If cooling is lost, the spent fuel can overheat, catch fire, and potentially release large clouds of radiation to the environment.

Cooling can be lost in a couple ways. If electric power to the plant is cut off, as it was following the earthquake and tsunami at Fukushima, the water can heat up and boil away. If water is not added fast enough (which it was at Fukushima) the fuel will overheat.

A second way to lose cooling is a leak in the pool, which would lead to a loss of cooling water even if there is still power. The biggest concern of this kind is a terrorist attack that physically damages the walls of the pool and drains water from the pool. In a 2006 study, the National Academy of Sciences said (p. 36):

“The committee believes that knowledgeable terrorists might choose to attack spent fuel pools because (1) at U.S. commercial power plants, these pools are less well protected structurally than reactor cores; and (2) they typically contain inventories of medium- and long-lived radionuclides that are several times greater than those contained in individual reactor cores.”

Because nuclear fuel has been piling up in cooling pools, a severe accident or terrorist attack could release radiation from a very large amount of spent fuel. How bad could such an accident be?

A recent study by the staff of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) analyzed a “loss of coolant” accident at the Peach Bottom nuclear plant in Pennsylvania. One scenario resulted in a fire of the spent fuel rods and the release of radioactivity that the study finds would lead to more than 17,000 cancer deaths, 9,400 square miles of evacuated territory—an area the size of New Hampshire—and more than 4 million people displaced long-term. (The first number uses the usual low-dose risk coefficient of 0.05 per person-Sv.)

Dry cask storage is safer than pool storage

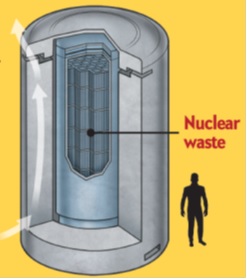

A safer alternative is to move a large amount of the spent fuel out of pools and into dry casks. Casks are large steel and concrete containers, each of which holds a small fraction of that stored in a pool. The casks would then be stored temporarily at the reactor site before eventually being moved to an interim or permanent repository. Plants have the cranes and other infrastructure needed to carry out these transfers. And since the fuel must be put in casks to be transported off site, the transfer from pools to casks must happen sooner or later. We think it should be sooner.

Fig. 3: Schematic of a dry cask. Spent fuel is surrounded by steel and concrete. Air currents cool the waste.

A big advantage of casks is that they use passive, rather than active, cooling. Air is pulled into the bottom of the cask, past the fuel, and out the top by the “chimney effect,” cooling the fuel as it does. So casks are unaffected by a loss of power at the plant. And if a cask were attacked, it would contain a relatively small amount of radioactive material. (Even so, plants should take steps to store casks safely.)

Reducing the amount of fuel in cooling pools lowers risk two ways. First, it reduces the chance that the spent fuel would overheat, burn, and release radiation into the environment if cooling was lost due to a terrorist attack or accident. Less spent fuel in a pool allows a wider spacing between spent fuel bundles, which improves cooling and reduces the chance that fire would spread between the bundles. Second, it reduces the consequences of an accident if the fuel does overheat: less fuel in the pool means less radioactivity that could be released.

Essentially no one questions that storing fuel in dry casks is safer than storing it in pools. However, the NRC believes that pool storage offers the public “adequate protection,” since it believes that the probability of a loss-of-coolant accident is very low. It therefore continues to oppose any requirements for accelerated transfers from pools to casks.

The NRC’s assessment, however, does not include the possibility of a terrorist attack or other possible scenarios. In an age when the NSA listens to phone calls of allied leaders due to concern about terrorism, the NRC’s assessment is not convincing.

Reduced consequences of an accident

How do the consequences of a pool accident change if you transfer fuel out of pools? The NRC study cited above compares the consequences of a spent fuel fire in the Peach Bottom pool today with the consequences assuming all spent fuel that had been in the pool longer than 5 years had been moved to dry casks. What it found was striking: after the transfer, the number of cancer deaths would be 10 times smaller and the amount of evacuated territory and number of long-term displaced people would both be 50 times smaller.

As I’ll discuss in a second post, while people argue about what the probability is that such an accident or attack might occur, taking steps to reduce the consequences should it occur only makes sense. This is completely in keeping with the NRC’s goal of “defense in depth.”

We’ve summarized the issues in an infographic on spent fuel transfers.