The owner of the Fort Calhoun nuclear plant in Nebraska recently informed the NRC about a design problem dating back to original construction in the 1970s along with several missed opportunities to correct the problem in the 1980s. The problem involves the penetrations for electrical cables passing through the thick concrete containment walls.

Commissioner William Ostendorff (left) recently toured Fort Calhoun and was briefed about ongoing efforts to rectify this longstanding problem. In April 2013, the NRC staff updated the Commissioner and his colleagues about the problem.

Sensors monitoring conditions inside the reactor and containment have electrical cables sending this information to instruments and computers outside the containment. Motors for pumps, valves, and dampers inside containment have electrical cable running to power supplies outside containment. Electrical penetration assemblies allow components inside containment to be connected to devices outside containment.

The electrical penetration assemblies must not fail in a way that compromises the integrity of the containment barrier. In other words, the electrical penetration assemblies must not cause a solid concrete wall to become a Swiss cheese barrier dotted with holes.

And those assemblies containing electrical cables for emergency equipment must protect the cables from damage caused by environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, humidity, radiation) during both normal operation and during accidents.

Not all cables passing through electrical penetration assemblies are connected to emergency equipment inside containment. For example, overhead lights allow workers to find their way inside containment during refueling outage. The electrical penetration assemblies for cables connected to non-emergency equipment need not protect such cables from damage, but these assemblies must still remain intact to preserve the containment barrier during normal operation and accidents.

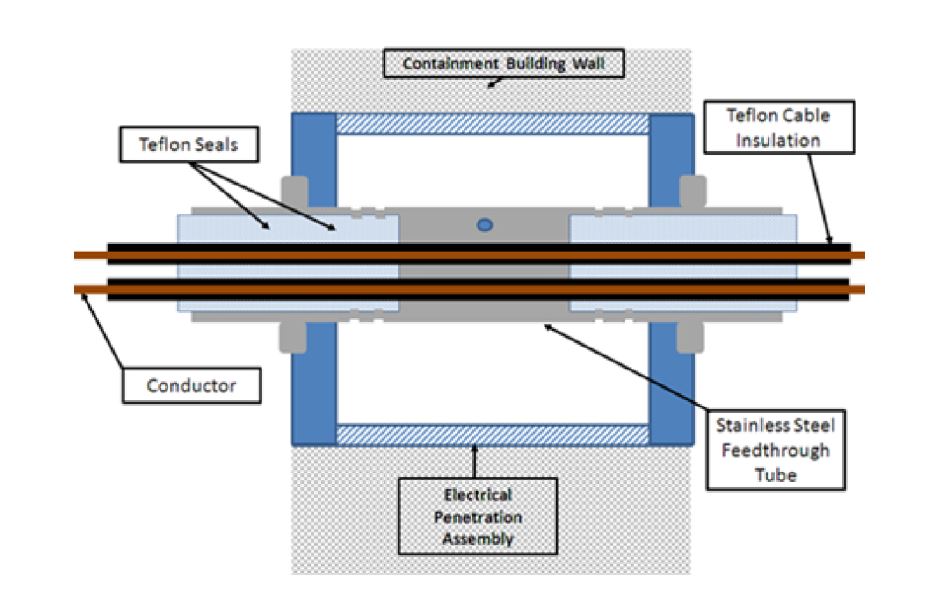

The schematic in Figure 2 shows a typical electrical penetration assembly for lower voltage electrical cables at Fort Calhoun. A hollow stainless steel sleeve is embedded in the containment’s concrete wall. Several smaller diameter stainless steel tubes run through the sleeve. Each tube allows one to twenty electrical cables to pass through the containment wall. Each electrical cable is coated with Teflon insulation for protection against environmental conditions. Each assembly has two Teflon seals to protection the containment’s integrity. (Either seal remaining intact preserves the integrity of the containment barrier; two independent seals are provided for redundancy.)

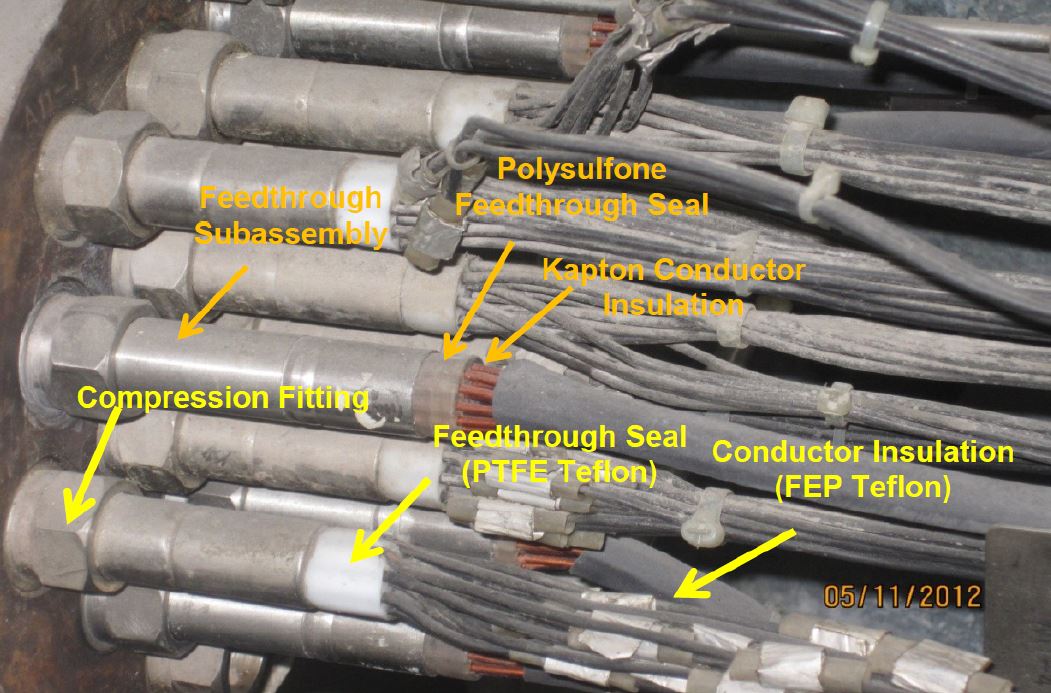

Figure 3 shows some of the electrical penetration assemblies at Fort Calhoun viewed from the reactor side of the containment wall. Various materials (i.e., Polysulfone and Kapton) are used in addition to Teflon for insulation and sealing.

The NRC issued Bulletin 79-01, “Environmental Qualification of Class 1E Equipment,” in 1979 to all nuclear plant owners, including that for Fort Calhoun, and subsequent mandates requiring that the owner qualify electrical equipment for the environmental conditions experienced during normal operation and accidents. These requirements covered electrical penetration assemblies.

Conax Buffalo Corporation, the vendor who supplied the Teflon-sealed assemblies for Fort Calhoun, conducted tests in 1971 and 1979. But the 1971 tests only involved the temperature, pressure, and humidity conditions expected inside containment during an accident and omitted radiation effects. And the 1979 tests did just the opposite; examining radiation conditions following an accident but neglecting the associated temperature, pressure, and humidity conditions. These segregated tests failed to verify the assemblies would survive the synergistic effects of all post-accident environmental conditions.

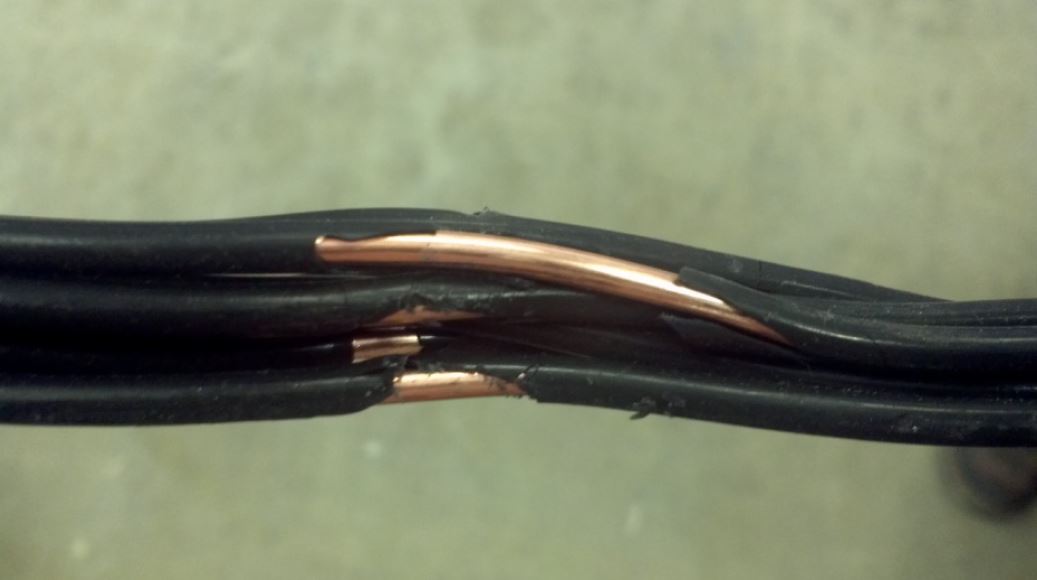

Fort Calhoun’s owner contracted with an independent laboratory to conduct comprehensive testing in 1983 and 1984 of the electrical penetration assemblies to account for thermal aging (i.e., the cumulative degradation from exposure to elevated temperature over many years) as well as exposure to radiation and steam during an accident. By a licensee event report dated July 23, 1984, the owner informed the NRC that a third of the assemblies tested failed. Sometimes, the Teflon insulation around individual electrical cables failed as shown in Figure 4. And sometimes the Teflon seal failed.

The owner informed the NRC in July 1984 that it would replace all 119 electrical penetration assemblies having Teflon seals that contained cables for equipment with safety or emergency functions. Another 375 containment electrical penetration assemblies at Fort Calhoun having Teflon seals contained electrical cables for equipment having no safety or emergency function. The owner made no mention of these assemblies to the NRC. While the failure of these assemblies could not disable cables for emergency equipment, their failure could turn the containment barrier into Swiss cheese during an accident.

As part of extensive re-evaluations being conducted since Fort Calhoun shut down in April 2011, workers discovered that only 113 of the 119 electrical penetration assemblies for safety equipment had been replaced and that none of the 375 electrical penetration assemblies for non-safety equipment had been replaced.

At the owner’s request, Westinghouse evaluated the Teflon-seal electrical penetration assemblies in 2012. This evaluation determined that the Teflon seal could fail in less than 40 years due to normal plant operation and could fail within minutes of exposure to conditions during an accident. Actual field testing of two spare electrical penetration assemblies at Fort Calhoun in November 2012 confirmed seal failure when exposed to post-accident conditions.

The NRC staff informed its Commission that:

- “ …since initial acquisition and installation of the Teflon insulated and sealed Conax electrical penetration assemblies, neither the licensee, nor its vendor, performed analysis or post-accident condition functional testing of the outboard seal despite information indicating the outer seal would fail…”.

- “Followup analysis to date reveals that the outer seal would be challenged and would affect the design basis function of the containment pressure boundary.”

- “The NRC staff assessed the Class 1E and non-Class 1E containment electrical penetration design function for containment integrity and with the use of Teflon on the inboard seal of the penetration, the outboard Teflon seal would not be able to meet its containment integrity function.”

Our Takeaway

The people living around the Fort Calhoun were adequately protected from harm during a reactor accident – unless a reactor accident happened. All too often, luck plays too large a role in protecting Americans from nuclear disaster.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the plant’s owner had information showing that hundreds of electrical penetration assemblies at Fort Calhoun were susceptible to failure from the environmental conditions inside containment during an accident. That vulnerability was dismissed on ground that each assembly had two seals – one at each end – and while the inner seal might fail, the outer seal would survive to save the day.

This “logic” reduces redundancy to a single barrier – the outer seal. The inner seal, which by design and by law is to be a fully redundant, independent barrier, was made sacrificial. With no testing results or even anecdotal evidence to support it, the outer seal was just assumed to withstand the conditions would cause the inner seal to fail.

It’s precisely the same flawed logic that enabled NASA to dismiss repetitive failures of the inner o-rings on the external fuel tanks of its space shuttles – until Challenger exploded seconds after launch in January 1986 when an outer o-ring failed for the same reason as its inner companion.

Omaha Public Power District (OPPD) may own Fort Calhoun, but it does not own all the blame for this fiasco. The NRC mandated that electrical equipment at Fort Calhoun be qualified for normal and accident environmental conditions. OPPD failed to comply. And NRC failed to notice. Not in the 1980s when the agency’s mandate was allegedly met, not in the 1990s following widespread awareness that original designs were often deficient (see NRC Information Notice 96-17 and Volume 14 of NUREG-1275 for many examples), and not in the 2000s when the NRC staff relicensed Fort Calhoun to operate for 20 more years. Both OPPD and the NRC had numerous opportunities to have detected this electrical penetration assembly problem long before 2012, yet all these opportunities failed to do so.

Once again, OPPD and NRC demonstrated that two wrongs don’t make a right. That’s not the kind of redundancy that properly serves safety.

It’s the same old song and dance, with the sole exception of the NRC having a new dance partner this time around.

In 1980, the NRC adopted fire protection regulations intended to prevent as serious a fire as ravaged the Browns Ferry nuclear plant in March 1975. It took the NRC nearly 20 years to discover that dozens of nuclear reactors did not comply with those regulations. In the late 1980s, the NRC required owners of pressurized water reactors to implement programs to protect essential components inside containment from damage caused by leaking boric acid after leaks caused damage at the Turkey Point (FL) and Salem (NJ) reactors. In the early 1990s, NRC inspectors audited the boric acid corrosion control program at the Davis-Besse nuclear plant in Ohio and found it inadequate in many key areas. But they did not follow up to ensure those known flaws had been remedied. And NRC inspectors virtually ignored clear evidence in fall 1999 that the flaws still existed when leaking boric acid severely damaged a vital component inside containment. In March 2002, the NRC had the gall to profess “surprise” when even more leaking boric acid ate a football-sized hole in the reactor vessel head at Davis-Besse.

Both OPPD and the NRC owe the American public some homework. Each should determine how all the many tests and inspections and evaluations over the years failed to notice that nearly 400 penetrations through containment were properly designed to remain intact during normal operation and during accidents. Just one adequate test, inspection, and evaluation over those intervening 30 years would have enabled the repairs being undertaken now to have been performed back then. More importantly, that effective test, inspection, or evaluation technique could be used to ferret out other undetected safety problems before our luck runs out and these pre-existing vulnerabilities cause an American Fukushima.

“Fission Stories” is a weekly feature by Dave Lochbaum. For more information on nuclear power safety, see the nuclear safety section of UCS’s website and our interactive map, the Nuclear Power Information Tracker.