Workers at the Brunswick nuclear plant south of Wilmington, North Carolina declared an Alert, the third most serious of the NRC’s four emergency classifications, on June 6, 2010. The fire protection system had inadvertently discharged Halon gas, a fire suppression agent, into the basement of the emergency diesel generator building. Halon gas functions like carbon dioxide discharged from hand-held fire extinguishers in putting out fire by robbing them of oxygen. There was no fire in the emergency diesel generator to put out, but the discharge of Halon gas into the area meant that workers, who also need oxygen, had to stay out.

Nuclear plants are staffed 24/7 with workers needed to operate the facility. In event of an off-hours emergency, like this one, the declaration of an emergency condition triggers a process where workers at home are notified about the emergency and instructed to proceed immediately to the plant and report to their assigned stations.

Three emergency response stations can be opened and staffed during an emergency: the Technical Support Center, which helps the operators mitigate the emergency; the Operations Support Center, which repairs damaged equipment and/or jerry-rig alternatives; and the Emergency Operations Facility, which interfaces between the plant and local, state, and federal authorities responding to the emergency.

Last century, the notification process to call in workers was manual. People would go down a list of names calling workers at home. In the 21st century, technological advances have replaced call-out lists with automated systems that send simultaneous electronic notifications to pre-programmed groups of workers.

At Brunswick last summer, those 21st century devices were handled by 20th century workers. The site emergency coordinator directed security personnel to initiate the emergency callout system. After five unsuccessful attempts to turn on the emergency callout system, the security staff informed the site emergency coordinator that they didn’t know how to make it work.

The site emergency coordinator then directed the control room emergency communicator to initiate the emergency callout system. After three failed attempts, the control room emergency coordinator gave up. An hour after the emergency had been declared, a worker at home was finally able to initiate the emergency callout system and other workers began receiving notifications to respond. The emergency response facilities were fully staffed 2 hours and 30 minutes after the emergency had been declared, a mere 1 hour and 15 minutes later than they should have been readied for business.

But that was not the only technological barrier encountered during this emergency at Brunswick.

Around the same time that security was instructed to initiate the emergency callout system, the Shift Technical Advisor (STA) was instructed to activate the emergency response data system (ERDS). The STA and the ERDS were additions to the emergency response palette through lessons learned from the Three Mile Island accident in 1979. The STAs are highly trained experts working 24/7 to provide around-the-clock technical support to the control room operators. The ERDS is a computer link between the plant and local, state, and federal authorities to provide them with key parameters on a real-time, continuous basis.

The STA did not know how to activate the ERDS. After several unsuccessful attempts, the STA contacted the on-call nuclear information technologist. The on-call nuclear information technologist also did not know to activate the ERDS, but knew another nuclear information technologist who might know. The first nuclear information technologist called the second nuclear information technologist who was able to remotely activate the ERDS. The EDRS went online 80 minutes after the emergency had been declared, 20 minutes later than it was supposed to be available.

The NRC sanctioned the plant’s owner with a White finding, the third most serious level, for its tardiness in staffing the emergency response facilities and a Green finding, the least serious level, for its tardiness in getting the ERDS up and running.

Our Takeaway

Ten years ago, workers responding to an emergency at the Indian Point nuclear plant in New York were slowed because a worker had mistakenly taken the only key to an emergency-response-facility room home. All the computers, gizmos, and gadgets were for nought because workers were on the wrong side of a locked door.

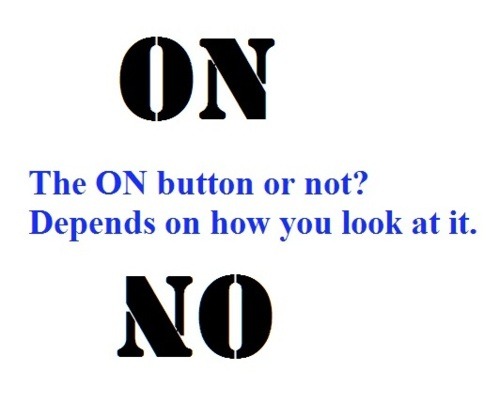

A decade later, response to an emergency declaration at Brunswick is delayed because workers could readily access the computers, gizmos, and gadgets but didn’t know how to turn them on.

Problems arise during actual emergencies because they do not surface during the testing of emergency systems. Emergency-system testing is typically scheduled weeks in advance, allowing workers most familiar with the systems and their use to participate and enabling the systems to be pre-checked for readiness. Actual emergencies are not scheduled in advance, forcing the workers on duty at the time to participate using systems that haven’t been verified to be ready the day before.

Emergency plans that only look good on paper tend to provide paper-thin protection.

“Fission Stories” is a weekly feature by Dave Lochbaum. For more information on nuclear power safety, see the nuclear safety section of UCS’s website and our interactive map, the Nuclear Power Information Tracker.