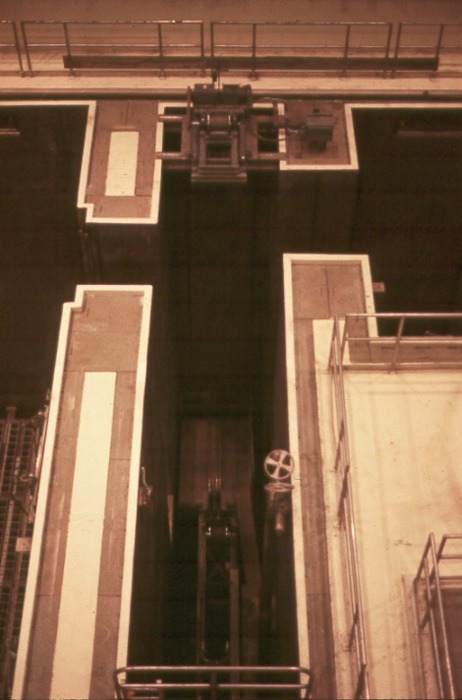

On July 14, 1991, the spent fuel pool cooling system at San Onofre Unit 3 in California was operating in its normal configuration. It took water from the spent fuel pool, cooled it, and returned the cooler water to the spent fuel pool and to the adjacent cask storage pool. The gate between the spent fuel pool and the cask storage pool was open. Figure 1 looks down on the transfer canal used for transferring fuel from the spent fuel pool outside containment and the reactor cavity inside it. To the left of the transfer canal is the spent fuel pool while the cask storage pool is on the right.

Figure 1

Figure 1

A dry cask, with its lid removed, is placed into the cask storage pool. The gates are removed, connecting all of these volumes. Irriadiated fuel assemblies are then moved underwater one-by-one from their storage locations in the spent fuel pool into the dry cask. Once loaded, the lid is placed on the dry cask and it is removed from the cask storage pool. Water is drained from the dry cask and replaced with an inert gas like nitrogen. The cask’s lid is permanently fastened and the cask relocated to an onsite storage pad. Figure 1 was taken during this plant’s construction, before the pools were filled with water.

Workers needed to perform maintenance in the cask storage pool. They installed the gate between the spent fuel pool and the cask storage pool. The valve in the piping returning cooled water from the spent fuel pool cooling system to the cask storage pool was mistakenly left open. With the gate installed, water added to the cask pool could not flow back to the spent fuel pool. The cask pool water level increased until it overflowed. About 5,600 gallons of water from the spent fuel pool flowed into the drains of the adjacent radwaste building. The drains filled and overflowed, flooding the radwaste building floor with about two inches of slightly contaminated water.

Our Takeaway

As in Fission Story #54, too much of a good thing can be a bad thing. In January 1919, too much molasses inside a storage tank in Boston caused an explosion that killed nearly a dozen and injured nearly four dozen others (see Figure 2). Goldilocks often holds the key to nuclear safety. It’s not too much flow (or temperature or pressure) or too little flow, but just the right amount of flow that makes everyone happy.

Figure 2

Figure 2

In this case at San Onofre, the value of monitoring conditions after making a change is illustrated. After workers installed the gate between the spent fuel pool and the cask storage pool, it would have been prudent to monitor conditions for a few minutes. The gate’s installation could have adversely affected cooling of the spent fuel pool. The gate’s installation could have – and did – adversely affect the water distribution between the pools. The easiest way to miss a problem is not to look for it.

“Fission Stories” is a weekly feature by Dave Lochbaum. For more information on nuclear power safety, see the nuclear safety section of UCS’s website and our interactive map, the Nuclear Power Information Tracker.