Nuclear plant control rooms have certain things in common. A horseshoe shaped collection of panels loaded with switches, dials, and instruments forms the main control station. Around and behind the main control panels are auxiliary panels.

At the Grand Gulf Nuclear Station in Mississippi, all the panels in the control room had locked doors. The Shift Supervisor dispensed keys to these locked panels.

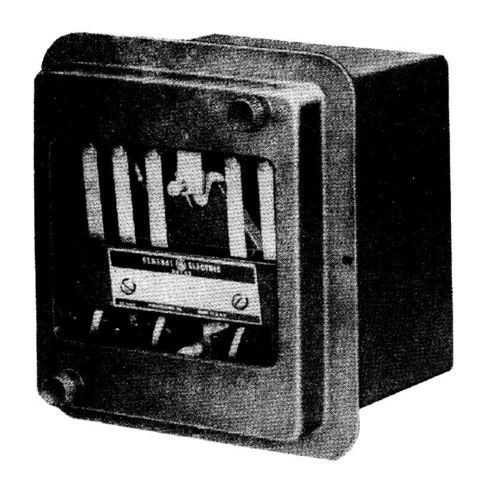

A member of the engineering department entered the control room one afternoon in the mid 1980s. He was working on the proposed replacement of some electrical relays with more reliable models. He wanted to see how the relays were installed in the panels to verify that the new relays would fit properly.

The engineer found the panel door locked. He said later that he didn’t ask the Shift Supervisor for the key because he felt the request would be denied. Instead, the engineer unscrewed the two screws holding the cover plate of the relay in place and removed it. He planned to peer in at the relay through the opening of the panel to check the measurements. That was his plan.

His reality was an automatic reactor shut down from 100 percent power. The engineer accidentally changed the position of the relay’s armature, generating a signal that automatically shut down the reactor. (The protection logic for nuclear reactors features two or more channels so one can be tested without causing the reactor to shut down. In this case, the engineer had the misfortune of tripping this relay when relays in the other channel were already tripped for a test.)

Nuclear power plant control rooms become extremely active following an unplanned scram. Dozens of alarms sound and many warning lights flash. Operators, highly trained for these moments, leap into action.

The engineer knew right away what he had done. While the operators took actions to stabilize the plant, the engineer quickly replaced the relay cover plate. He left the control room and walked back to his office in the engineering building about half a mile from the plant.

Before the engineer got back to his office, the operators had stabilized the plant. They began investigating the cause of the unplanned scram. Plenty of information was available, but it didn’t make sense. They quickly determined which relay had operated to trip the plant. However, none of the transmitters out in the plant which send signals to operate the relay sent such a signal. An inspection of the relay showed it to be in proper working order. For an unknown reason, that relay caused the reactor to trip.

Then the phone rang in the control room. It was the engineer’s supervisor. He reported what had happened. The plant manager was not pleased. Not pleased at all. Not even close. And speaking of not even close, the plant manager did not allow that engineer and his colleagues to get even close to the plant for several days.

Our Takeaway

As comedian Ron White observed, “you can’t fix stupid.” When you intentionally work around the administrative controls established to control access to vital equipment, you use up all your “Get Out of Jail Free” cards. The engineer was lucky to have kept his job after having lost his wits.

“Fission Stories” is a weekly feature by Dave Lochbaum. For more information on nuclear power safety, see the nuclear safety section of UCS’s website and our interactive map, the Nuclear Power Information Tracker.