On March 11, 2011, a large earthquake with an epicenter a few miles off the northeastern shores of Japan spawned a tsunami that inundated the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant. The earthquake disconnected the plant from the offsite power grid. The tsunami disabled the onsite emergency diesel generators. Deprived of electricity for emergency systems, the reactor cores for Units 1, 2 and 3 overheated and melted down.

On March 12, 2012, the Nuclear Regulatory Committee (NRC) ordered owners of US nuclear power plants to develop and implement mitigation strategies to reduce the vulnerabilities of their facilities to extreme earthquakes and floods. While the specific measures varied from plant to plant, the mitigating strategies generally involved portable pumps, portable generators, cables, hoses, and hauling equipment (called FLEX equipment) and associated procedures for workers to use should permanently installed equipment become disabled.

While the NRC’s order and the industry’s FLEX equipment were intended to reduce vulnerabilities to hazards over and above those deemed credible when the nuclear plants were designed and licensed, Dominion Energy has figured out how to use the new equipment to lessen old risks at its Surry nuclear plant, thus reaping a nuclear safety dividend from its Fukushima investment.

Surry’s Internal Flooding Risk

The Surry Power Station is located about 17 miles northwest of Newport News, Virginia. The nuclear plant has two three-loop pressurized water reactors designed by Westinghouse. Each unit can supply 838 megawatts of electricity to the offsite power grid. Unit 1 commenced commercial operation in December 1972 and Unit 2 followed in May 1973.

Fig. 1 (Source: Dominion Energy)

The large white rectangular structures in the center of Figure 1 are the turbine buildings with the two reactor containments on the left. The turbine buildings contain the turbine generators used to make electricity. The turbine buildings also house the emergency switchgear rooms that route electricity from the offsite power grid, onsite emergency diesel generators, and onsite battery banks to safety equipment throughout the plant.

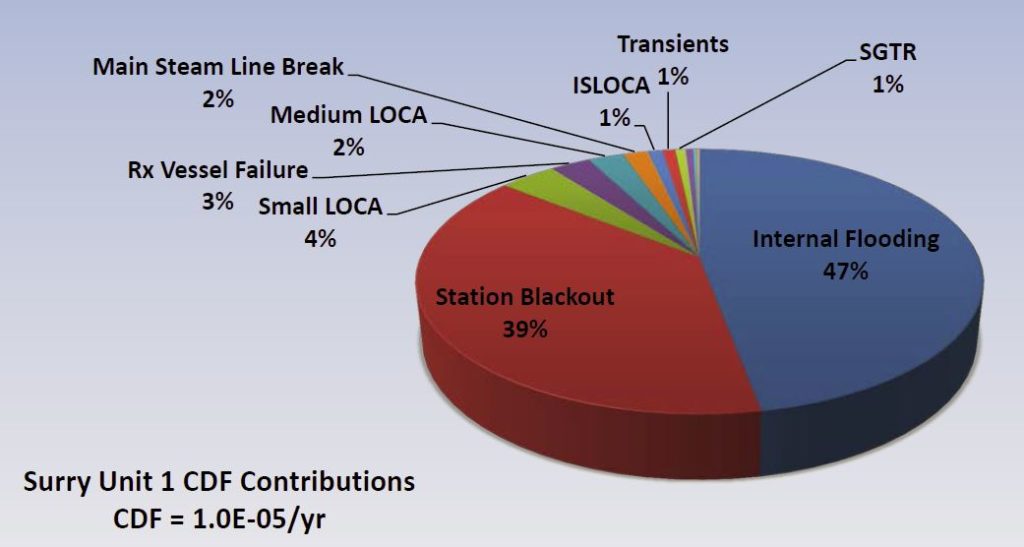

It has long been recognized that a large risk of reactor core damage at Surry was an internal flood that caused water to enter the switchgear rooms and disable their electricity distribution capabilities. Figure 2 shows that this internal flooding risk constituted 47% of the overall risk of reactor core damage at Surry, or nearly equal to all other hazards combined (CDF refers to core damage frequency).

Fig. 2 (Source: Dominion Energy)

If water from an internal flood enters the switchgear room and disables the supply of electricity to safety equipment, Surry has turbine driven auxiliary feedwater (TDAFW) pumps that would continue to provide makeup water to the steam generators so that decay heat produced by the shut-down reactor cores would be removed. The TDAFW pumps are powered by steam produced by the reactor core’s decay heat in the steam generators.

But the TDAFW pumps could be deprived of their automatic control system during an internal flooding event and the event could also disable the instruments that workers need to manually control the pumps. If the TDAFW pumps overfill the steam generators due to inadequate control of their flow rates, the steam flow for the pumps would be stopped which in turn halts the removal of decay heat from the reactor cores. If cooling cannot be restored in time, meltdown happens.

The turbine buildings are filled with pipes transporting water here, there and everywhere. Some pipes move water from the intake canal shown on the right in the photograph through the condensers beneath the main turbines and return it to the discharge canal appearing to the left of the reactor containment domes. Other pipes carry cooling water to equipment within the turbine buildings. And other pipes recycle water from the condensers to the steam generators located within the reactor containments.

The internal flooding hazard involves one of these pipes breaking and flooding the turbine building with water until a valve can be closed to isolate the break or a pump turned off to stop the flow. Depending on which pipe broke and how long it took to stop water pouring from its broken ends, the turbine building will be flooded to a certain depth. Figure 3 shows a dyke installed in the turbine building outside the doors to the emergency switchgear room for protection against internal flooding.

Fig. 3 (Source: Dominion Energy)

Dominion Energy built a concrete building at Surry and filled it with FLEX equipment as part of its response to the NRC’s mitigating strategies order. Figure 4 shows some of the FLEX equipment housed within this new building.

Fig. 4 (Source: Dominion Energy)

Surry’s Internal Flooding Risk Reduction

The NRC’s order and Dominion Energy’s FLEX equipment were intended to reduce the vulnerability of Surry to hazards posed by earthquakes and external floods more severe than anticipated when the plant was designed and licensed. Permanently installed equipment mitigate anticipated internal and external hazards; FLEX provides workers alternative means to cope with greater hazards.

Dominion Energy developed the capability for its FLEX equipment to also lessen the internal flooding risk. A Remote Monitoring Panel (RMP) was installed at Surry in response to the fire protection regulations imposed by the NRC in 1980. If a fire forced workers to abandon the main control room, they would relocate to the RMP which had switches and instruments needed to cool the reactor cores.

Dominion Energy modified the RMP to enable the FLEX equipment to provide power for its controls and instruments. If an internal flooding event disabled the electricity distribution from the switchgear rooms, workers could connect FLEX equipment to the RMP and increase their chances of successfully cooling the reactor cores until permanently installed systems could take back over that role. Figure 5 shows that the FLEX equipment significantly reduces the internal flooding and station blackout risks. Because these pose the two largest risks of core damage at Surry, reducing them also reduces the overall core damage risk, and by more than a smidgen or even two smidgens.

Fig. 5 (Source: Union of Concerned Scientists based on data from Dominion Energy)

UCS Perspective

Dominion Energy achieved a safety two-fer—the equipment procured to reduce Surry’s vulnerability to external hazards has also been able to reduce the plant’s risk from internal hazards.

UCS applauds this approach to nuclear safety. The FLEX equipment did not replace existing equipment; it supplemented it. In this way, workers are provided more options and thus given greater chances of successfully intervening to prevent bad outcomes.

We remain concerned—not specifically at Surry or by Dominion Energy but more generally—that FLEX will be used to justify increased risks. As a hypothetical example, suppose someone’s flood protection dyke broke when workers accidentally rammed it with an equipment cart. Justifying not fixing the broken flood barrier because of the FLEX safety net would be disappointing.

Similarly, justifying the elimination of inspections of pipes inside the turbine building for signs of degradation by reliance on the FLEX safety net would also be disappointing. The inspections detect degraded pipes for their replacement before they rupture, thereby reducing the need for a reliable safety net.

Drivers of vehicles equipped with airbags should not justify driving while intoxicated or blindfolded or both citing the airbags as their safety net. That’s a safety not rather than a safety net.