Disaster by Design/ Safety by Intent #56

Safety by Intent

The Nuclear Waste Policy Act (NWPA) of 1982, as later amended in 1987, is best known for tasking the Department of Energy (DOE) with siting, constructing, and operating a geological repository for the long-term disposal of spent fuel from commercial nuclear power plants. It is less well-known that Section 306 of the NWPA tasked the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) with enacting regulations for the training and qualification of nuclear power plant workers.

The DOE has thus far failed its assigned mission and the federal government has paid out several billion dollars to parties across the country for damages incurred as a result of the failure. Fortunately, the NRC succeeded—albeit with some prodding from a public interest group and the courts—in its assigned mission, and not just by comparison to DOE’s ineptitude.

The need that prompted this NPWA provision stemmed from the March 1979 accident at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania. Post-accident inquiries conducted by the NRC and the Congress concluded that the operators at Three Mile Island, and throughout the nuclear power industry, had not been provided sufficient training to enable them to effectively respond to accidents. As a result, the operators at Three Mile Island were set up for mistakes that increased the severity of the accident.

The NRC Path to Regulations

On February 13, 1984, the NRC staff outlined a rulemaking plan (SECY-84-76) that would develop regulations governing training and qualification programs for nuclear plant workers and satisfy the requirements of Section 306 in the NPWA.

The nuclear industry opposed the rulemaking plan. Instead, the industry sought to self-regulate training programs and recommended that the NRC merely adopt a policy statement on training rather than develop regulatory requirements. By a 3-2 vote, the Commission sided with the nuclear industry rather than its own staff by directing that a policy statement rather than a regulation be developed. One of the dissenting voters, Commissioner Victor Gilinsky, wrote that “In pressuring the Commission to accept a feeble approach toward shift experience requirements, the industry is jeopardizing its long standing safety record.” The NRC’s policy statement on training and qualification of nuclear plant workers was published in the Federal Register on March 20, 1985.

Public Citizen, a public interest group founded by Ralph Nader, petitioned the NRC in 1986 contending that the policy statement did not satisfy the NRC’s obligations under the NPWA to issue regulations. The NRC denied Public Citizen’s petition on January 14, 1987.

The NRC published an updated policy statement on nuclear plant worker training and qualifications in the Federal Register on November 18, 1988. Public Citizen filed a suit in the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit contending that policy statements did not satisfy the NWPA. The court decision issued in April 1990 supported Public Citizen’s contention. The court wrote that “When Congress gives the agency its marching orders, the agency must obey all of them, not merely some.” The industry appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, but the Supremes declined to get involved.

The NRC staff submitted another proposed rulemaking plan for nuclear worker training to the Commission on April 25, 1991 (SECY-91-108). This time, the Commissioners’ vote was not split—the Commissioners unanimously rejected the proposed plan as being overly broad and too prescriptive.

The NRC staff tried again. They submitted a third rulemaking plan to the Commission on December 16, 1991 (SECY-91-371). This rulemaking plan proposed regulations requiring each owner to implement training programs for nuclear plant workers derived from a systemic analysis of job performance needs. Once again, the Commissioners voted unanimously on the plan; this time to publish the draft regulations for public comment. The final regulations were published in the Federal Register on April 26, 1993. Along the way, the NRC issued a report describing the criteria it would apply when determining whether training programs for nuclear workers conformed to the new regulations.

(For additional details and sources see a white paper recently issued by the NRC staff on the history of nuclear plant training and qualification requirements.)

Destination of the Long and Whining Road

The path to regulations on nuclear plant worker training and qualifications was certainly bumpy, cumbersome, and slow. Nevertheless, the destination reached by that tortuous process yielded positive safety improvements.

Training and qualification requirements existed for nuclear plant workers prior to the Three Mile Island accident. Before being licensed as control room operators, individuals had to demonstrate proficiency on written and oral examinations. Standards defined qualifications needed for other nuclear plant workers.

Today’s training programs and qualification standards are significantly different. Control room simulators may best illustrate the wide gap between conditions then and now. Simulators are full-scale replicas of nuclear plant control rooms (Fig. 1). The real control room’s switches, gauges, computer screens, alarms, and such connect to equipment in the plant. The simulator’s switches, gauges, computer screens, alarms, and such connect to a computer. Fidelity requirements ensure what happens in the simulator very closely models what happens in the real plant.

Fig. 1 (Source: Dave Lochbaum

Back then, many owners did not have simulators. Instead, they sent workers to offsite simulators operated by reactor vendors. Workers’ access to simulators was limited during their initial training and even more restricted during periodic retraining. Now, simulators are readily available for all plants. Greater access affords greater use. Control room operators routinely spend every sixth week in retaining either in classrooms or in simulators. They receive formal training on modifications to the plant and its procedures. They must demonstrate proficiency applying that acquired knowledge in the simulator. In addition, workers commonly spend time in the simulator refreshing their awareness of tasks they have not performed in awhile before executing them “live” in the control room.

The expanded use of simulators reflects increased emphasis on applied knowledge and skills. The NRC’s regulations requires that training programs be built on a foundation of knowledge and skills needed for workers to perform their jobs. The NRC developed what it called “catalogs” identifying the knowledge and abilities needed by operators of pressurized water reactors (PWRs) and boiling water reactors (BWRs). The current PWR catalog contains nearly 5,100 items while the current BWR catalog lists nearly 7,000 items.

The catalogs are used by the NRC in the examinations it administers to individuals seeking licenses and control room operators.

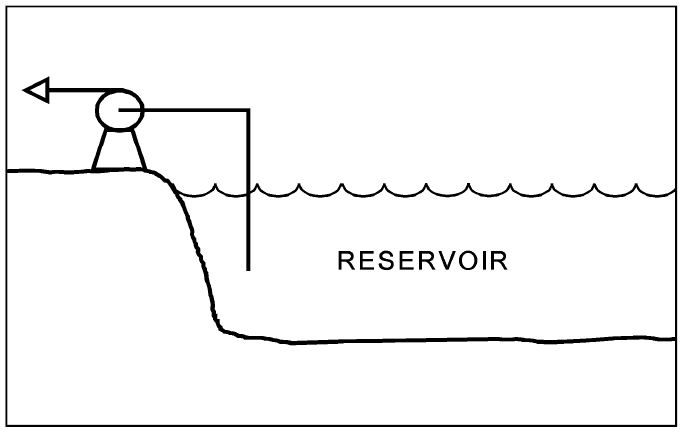

For example, a recent NRC exam asked this multiple-choice question referring to the simple graphic (Fig. 2):

Fig. 2 (Source: Nuclear Regulatory Commission)

A pump is located on shore, with the eye of the pump 4 feet higher than the reservoir’s water level. The pump’s suction pipe extends 4 feet below the surface of the reservoir. Which one of the following modifications would increase the pump’s available net positive suction head?

- Raise the pump and suction line by 2 feet.

- Lower the pump and suction line by 2 feet.

- Lengthen the suction pipe to draw water from 2 feet deeper in the reservoir.

- Shorten the suction pipe to draw water from 2 feet shallower in the reservoir.

The best (and correct) answer was B.

Prior to Three Mile Island, candidates might have been asked to define net positive such head for a pump or to calculate it given information about key parameters. Now, the NRC still tests candidates about net positive suction head, but do so from a more applied knowledge perspective.

The NRC reported that 85 to 89% of the candidates passed the agency’s written examinations administered over a 10-year period. This passing rate suggests that the examinations are reasonably challenging. If all candidates passed, one would wonder about the usefulness of the tests.

Bottom line, the training of nuclear plant workers—whether they are control room operators, maintenance workers, system engineers, radiation protection specialists, security force personnel, and others—is considerably broader and better than it had been prior to Three Mile Island. Better training may not be the only reason it has been 37 years since that accident, but it certainly contributes to that outcome.

Disaster by Design

Nuclear plant worker training is vastly improved over training received four decades ago. However, it’s not time to declare “Mission Accomplished” and fold the training tent. Disaster by Design #20 earlier this year chronicled six recent events at nuclear power plants worsened by training deficiencies. Fission Stories #58 provided additional details on one of the six events.

Fission Stories #80 also provided additional details on one of the six events. The owner had eliminated training of workers for certain tasks performed during refueling. Years later, untrained workers failed to put the head back on the reactor vessel. They misunderstood both of the methods used to determine if the head was properly re-installed.

As both the NRC and the nuclear industry struggle to downsize, we hope that training programs will not be scaled back or eliminated just to save a few bucks. The Three Mile Island accident taught us the value of training. It would be irresponsible for training programs to be slashed until another accident shows us those cuts were too much.

If it ain’t broke, don’t break it.

—–

UCS’s Disaster by Design/ Safety by Intent series of blog posts is intended to help readers understand how a seemingly unrelated assortment of minor problems can coalesce to cause disaster and how effective defense-in-depth can lessen both the number of pre-existing problems and the chances they team up.