Last week, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) finalized updated regulations for certain facilities that emit ethylene oxide (EtO), a colorless, cancer-causing gas. These long-awaited rules will require facilities using EtO to sterilize medical devices and some food products—known as commercial sterilizers—to significantly reduce their emissions of EtO, install additional control equipment, and improve monitoring.

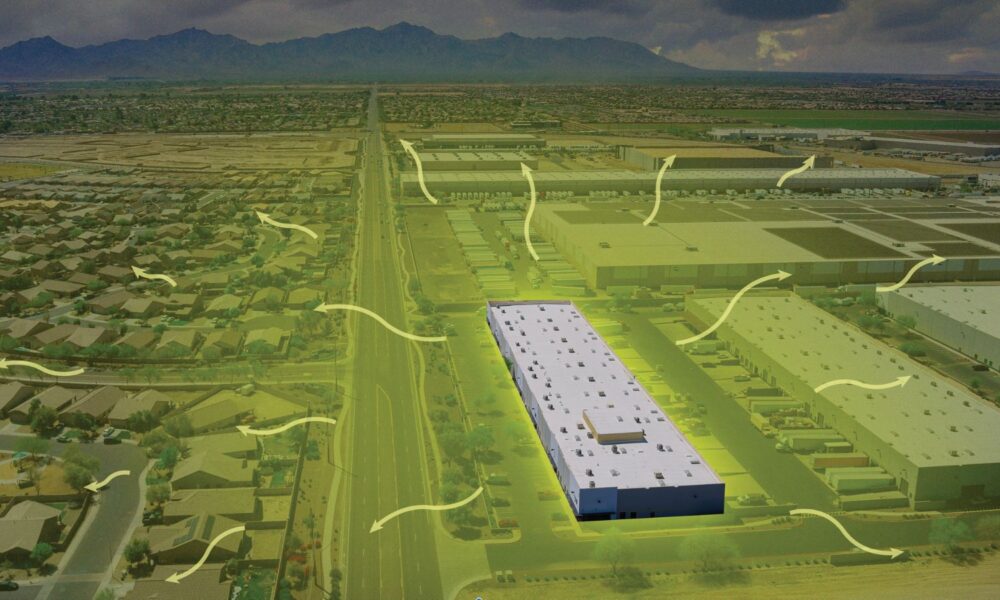

Ethylene oxide is used in chemical manufacturing, as well as sterilization, due to its effectiveness at killing microbes. However, mounting evidence has shown its harms to both workers and community members. Short-term, elevated exposure by inhalation can cause respiratory irritation, nausea, blurred vision, and headaches, and long-term exposure increases people’s risk of developing certain types of cancer, including white blood cell cancers and breast cancer. Children are especially vulnerable to exposure because EtO is a mutagen, meaning it can damage a cell’s DNA, and children’s cells divide more rapidly than adults’ cells do. And its effects can be “invisible” to many, as these sterilization operations are often housed in nondescript warehouses near other businesses and residential areas where people are often unaware of what is being emitted in their community.

The new rule will offer a significant boon to public health. An analysis by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) last year found that more than 13 million people live within five miles of commercial sterilization facilities, with 10,000 schools and childcare centers in these same areas. Our report revealed that sterilization facilities are disproportionately located near people of color and people who do not speak English as a first language. We also found that co-located sterilization facilities, facilities in communities with higher cancer risks, and facilities that have violated the Clean Air Act are disproportionately near people of color, illustrating the vast disparities of who this pollutant impacts most. You can find our report and interactive map here.

This rule stands to alleviate the burden of EtO exposure in these communities across the country. Let’s review what EPA did well and where the agency fell short in the final rule.

Sterilization facilities must reduce EtO emissions

The key victory in this rule is that EPA will now require a combination of control measures and emissions limits at sterilization facilities. For the first time, the government will regulate fugitive or “unintended” emissions and require permanent total enclosure of sterilization operations. According to EPA, these controls could reduce EtO emissions at sterilization facilities by 90 percent.

Notably, the EPA also updated its risk review to consider “allowable” rather than “actual” emissions—a change that the agency says it considered after comments made by UCS and our partners. This important development ensures that the risks are assessed based on the maximum amount a facility can emit, rather than what the facility self-reports. Since estimated cancer risks were greater when considering allowable emissions, EPA was able to finalize additional control measures from what was originally proposed to bring these risks down to an “acceptable” level. This is encouraging, as EPA was able to strengthen its risk review in the final rule, leading to even stronger standards.

Still, EPA also notably weakened some provisions in the final rule compared to the draft, or elected not to adopt them, despite a push for them in many public comments, including the one submitted by UCS and our partners.

Compliance delayed

One notable area in which the final rule falls short is in its compliance deadlines. The proposal initially provided sterilization facilities 18 months to comply with the requirements in the final rule—which is already longer than the minimum time required under the Clean Air Act (CAA). Instead, in response to comments made by the sterilization industry, EPA significantly lengthened the compliance deadlines in the final rule. Depending on the size of the facility, sterilizers will now have two to three years, with possibility of a one-year extension for some.

This is extremely disappointing, as it means that communities may continue to be unnecessarily and unknowingly exposed to hazardous levels of EtO for even longer. It is also puzzling because EPA asserts that, “a number of the facilities covered by this final rule have already implemented one or more of the controls that will be needed for compliance,” therefore one might assume that achieving full compliance would not require so much additional time. Furthermore, the risks of EtO have been known for decades now and should not be a surprise to the industry. As I’ve previously reported, in 2005, when EPA last reviewed these standards, the agency considered banning the use of EtO for new sterilization facilities altogether, but ultimately did not adopt the proposal due to industry pushback.

Accountability measures weakened or not addressed in final rule

Grassroots advocates and residents of communities with sterilization facilities also asked for a number of provisions that EPA did not adopt. First, EPA acknowledged that many comments argued that these regulations should extend to off-site or stand-alone warehouses, where companies often store newly sterilized material that continues to “off-gas” or emit EtO. These concerns were related to warehouses such as one in Covington, Georgia that was found to be releasing such high levels of EtO, that it would have required an air quality permit. EPA ultimately decided not to extend coverage of these regulations to off-site warehouses, in large part because they, “do not have sufficient information to understand where these warehouses are located, who owns them, how they are operated, or what level of emissions potential they may have.” It is disconcerting whenever any federal agency states that a lack of data—particularly data they should require companies to submit—is a reason to shirk regulation. Furthermore, this loophole raises concerns of whether it could incentivize companies with on-site warehouses to simply move their storage off-site to evade regulatory oversight. EPA did state that it plans to gather information about off-site warehouses and potentially develop new regulations for these sites. We urge the agency to do so promptly to ensure that data on where these warehouses are located is made public and emissions are properly controlled.

Many commenters also called on EPA to require sterilization facilities to install fenceline air monitors near the facility property line to measure ambient air emissions to which adjacent communities might be exposed. EPA opted not to require fenceline monitoring in the final rule, which would have provided an additional layer of oversight to ensure that the controls were reducing community-level exposure. That being said, the agency did strengthen emissions monitoring and reporting requirements from control equipment, which should provide helpful data on compliance.

And finally, the EPA decided to scrap a proposal requiring certain sterilization facilities to obtain a Title V operating permit. Title V permits offer an additional level of accountability that also expands public participation in the permitting process. Overall, while the rule significantly strengthen emissions limits and control requirements, we are concerned that EPA also weakened or failed to adopt provisions that would ensure accountability and compliance with these regulations.

A long-awaited win, with more to go

These regulations represent a major win for public health and grassroots advocates across the country. But it is important to note that they are a decade overdue. Under the Clean Air Act, EPA is required to review and revise standards for “hazardous air pollutants” (including ethylene oxide), every eight years. Prior to last week, regulations for commercial sterilizers had not been reviewed in nearly two decades and had been due for review in 2014. This means that people were unnecessarily, unknowingly, and unlawfully exposed to ethylene oxide for years, with consequences that may not be known for years to come.

Still, we share our immense gratitude to community advocates at Rio Grande International Study Center, Memphis Community Against Pollution, Clean Power Lake County, and Stop Sterigenics, among many others, for tirelessly pushing EPA to do better. Our partners at Earthjustice also successfully brought a lawsuit that required EPA to strengthen these standards.

This is the second major rule EPA has finalized this month to reduce chemical exposure hazards in communities across the country. We encourage the agency to maintain this momentum to continue reviewing and updating rules for facilities that emit ethylene oxide, including hospital sterilizers, which have major implications for health care workers, and synthetic organic chemical manufacturing (HON) facilities, which are often concentrated in already overburdened communities.

All communities exposed to EtO and other hazardous air pollutants must be afforded protections from harmful emissions.