Over the past several years, one of the few pieces of hopeful news about global warming has been the annual release of data from Brazil on its rate of Amazon deforestation. Since forests are immense storehouses of carbon, deforestation causes high levels of greenhouse gas emission. Brazil, which contains about 60% of the Amazon forest, is key to those emissions, and over the last six years it has made important progress in reducing its deforestation rate.

Today, the new data for 2011-2012 were released, and once again they are a ray of sunshine on an otherwise gloomy day. They show a decrease of deforestation to 4,656 square kilometers – down 27% from last year.

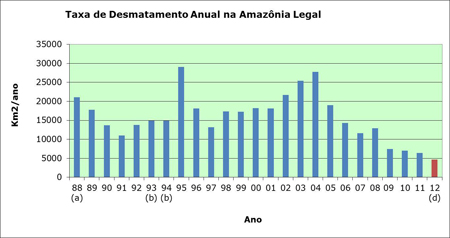

Here’s the graph of the data:

Deforestation in the Brazilan Amazon since 1988, in square kilometers. The latest year (2011-2012) is shown in orange. SOURCE: National Institute for Space Research (INPE), Brazil.

As you can see, the trend since 2004 is steadily downward. In fact, compared to the average from 1996 to 2005, which Brazil uses as its baseline, deforestation has now fallen by more than 75%. We’ll be looking at the new data in coming days to find out more about how and where this drop occurred – which states, what size of farms, etc. But based not only on the new numbers but also the trend over the past several years, there are already some important things to say about it. (Full disclosure/author’s confession: a good deal of the sentences that follow are “self-plagiarism” – text that I’ve modified from the summary of a forthcoming article of mine in the journal Tropical Conservation Science, entitled “Brazil’s Success in Reducing Deforestation”. I originally put this together as a talk at the January 2011 conference organized by the Yale chapter of the International Society of Tropical Foresters.)

Marina Silva, first Minister of the Environment in the Lula government, who led the effort to reduce deforestation in Brazil.

There’s no doubt that what Brazil has done is a major, indeed historic success. It has come despite economic pressure in the opposite direction, from high global prices for soybeans and beef, the two major drivers of deforestation in the Amazon, and from the increased demand brought about by urbanization in the region. It represents the largest reduction in global warming pollution achieved by any country so far, and the majority of its cost was paid for by Brazil itself. It came during a period in which the country substantially reduced poverty and hunger and in which the economy and its agricultural output, including that of the soy and beef industries, grew rapidly.

Lots of people deserve credit for this accomplishment. They include former President Luis Inacio Lula da Silva, and particularly his first Minister of the Environment, Marina Silva, as well as current President Dilma Rousseff. Important contributions came from strong enforcement of environmental laws by public prosecutors; from major steps taken by several state governments, and because of the incentive provided to Brazil by Norway via results-based funding through its forest-climate program. The actions of Brazilian civil society, in pushing both governments and the industries driving deforestation as well as changing the political dynamic, were a critical element. The pressure these actions exerted led to exporters adopting voluntary moratoria on buying soy and beef from deforested lands, which have greatly reduced the economic incentives that previously encouraged commercial farmers and ranchers to deforest.

As in past years, the announcement of Brazil’s success came during the annual climate negotiations of the UNFCCC, this year in Doha, Qatar. And also as in past years, the contrast between what Brazil has done, and what the climate negotiators haven’t done, is stark. But at least in one very important part of the world, people have taken climate change seriously, and are doing something about it.