I’m in New York City for the United Nations Climate Summit, and it’s an important week for tropical forests and the global climate.

On Sunday I joined over 300,000 people in marching through the streets of Manhattan to tell the world’s leaders assembled here at the U.N. that they need to cut global warming pollution now. On Monday a special event on forests and Indigenous Peoples at the Ford Foundation showed the vital roles that indigenous communities have played in reducing tropical deforestation, which accounts for about 10 percent of global emissions. It was also the occasion for the U.K. and Norway to pledge substantial new funding for forests.

On Tuesday, a major statement by governments, NGOs (including UCS), and businesses – the New York Declaration on Forests – will be released, committing to a broad and ambitious effort to end deforestation and regrow forests that have been lost. Those are three important steps forward, and they help to counter the confusion caused by an op-ed in the town’s “newspaper of record,” the New York Times, in a misleading piece on Saturday.

Nadine Unger’s piece, entitled “To Save the Planet, Don’t Plant Trees” used the argument that forests actually absorb more sunlight and reflect less of it than cleared areas do. Thus Unger claims that saving forests and planting new ones on a large scale “can actually make global warming worse.”

This is presented as a dramatic new challenge to the conventional wisdom, but in reality, ecologists have considered this point in detail in recent years, and have found it pretty much irrelevant to preventing tropical deforestation (nearly all deforestation today is in the tropics). It’s also only weakly linked to the value of restoring these forests when they have been cleared. The reflection or absorption of solar radiation (the albedo effect) is relatively important only in high latitudes — the boreal forests and tundra — where snow cover on the ground in the winter contrasts dramatically with the darker color of evergreen forests. On the other hand, in the tropics the stock of carbon in forests is much larger and they grow year-round at much higher rates than in the far north. And obviously, the reflection of sunlight by snow-covered ground is, shall we say, of lesser importance in the tropics.

Snow-covered tundra in northern Russia. Photo: United Nations Environment Program

Furthermore, Unger asserts that because biogenic Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) produced by trees interact with fossil fuel pollution to create greenhouse gases, more trees are a problem. But surely reducing fossil fuel pollution is the most direct and effective way to reduce this effect, not blaming the forest.

So the balance of impacts is pretty clear: in the tropics, where almost all deforestation takes place and where reforestation could take large amounts of carbon dioxide out of the air, the issues raised by Unger are of minor importance. In fact, a more accurate title for her article would be: “To Save the Planet, Don’t Plant Trees in Northern Canada and Russia.” Put that way, it doesn’t sound all that important.

Far more relevant to the future of our climate is the recognition of indigenous land rights, highlighted at the event at the Ford Foundation sponsored by the Climate and Land Use Alliance, CLUA (full disclosure – CLUA has funded our work for several years).

In the world’s tropical forest regions — particularly the Amazon, which is the largest — effective indigenous land tenure is having a big impact in reducing deforestation rates. As shown in a new report released at the event, and as we’ve explained in our recent report on Deforestation Success Stories and in various journal articles, indigenous communities choose to keep almost all their land in forest when their land rights are recognized and effectively enforced.

Thus in the Brazilian Amazon, where more than 20 percent of the forest is in indigenous reserves, these lands have 90 percent less deforestation than comparable land controlled by others. Indigenous Peoples are thus important protectors and stewards of tropical forests, making recognition of their collective land rights a highly effective way to safeguard forests and slow climate change.

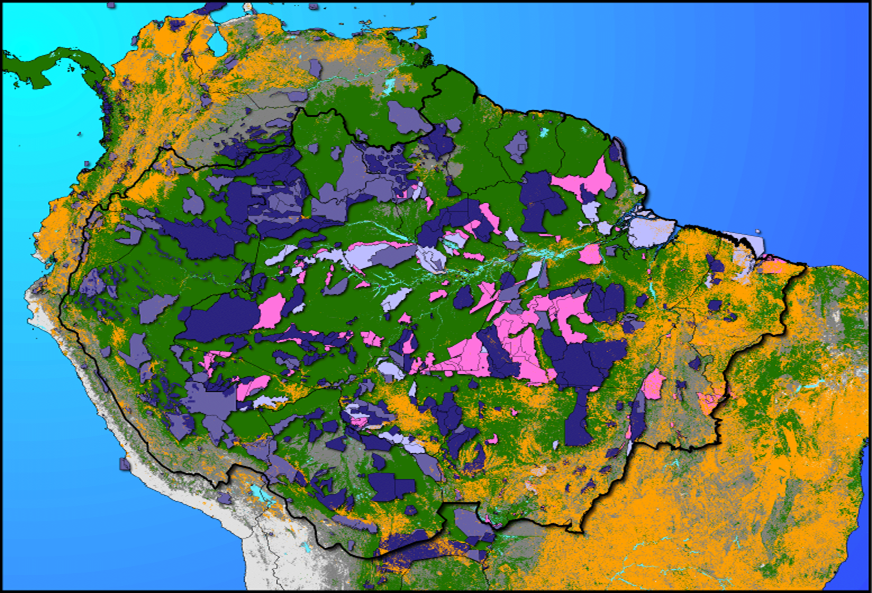

Lands reserved for indigenous peoples (dark purple), or protected by federal and state governments (pink and light purple), now cover over half of the Amazon Basin of Brazil. Image: Ricketts, T.H. et al. 2010. Indigenous lands, protected areas, and slowing climate change. PLoS Biology 8: e1000331

The event at the Ford Foundation was also the occasion for important financial pledges by donor governments. The U.K.’s Secretary of State for International Development, Justine Greening, announced an additional commitment of about $100 million for work with businesses to eliminate deforestation from their supply chains, while Hans Bratskar, State Secretary of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, confirmed that they will contribute $100 million for enforcement action to support deforestation-free supply chains and another $100 million to support indigenous communities’ efforts on the issue of land rights.

We’re now waiting expectantly for the release of the New York Declaration on Forests at U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon’s Climate Summit on Tuesday. It’ll show that governments, businesses and other organizations (including UCS) are willing to commit themselves to the massive global effort to end deforestation and begin restoring what has been lost.

In the People’s Climate March on Sunday, I was proud to join UCS colleagues and supporters in carrying a banner with the slogan “Friends Don’t Let Friends Deny Reality.” Amusing, but also all too relevant to global climate policy today. Let’s hope that this week in New York City, the reality of climate change will finally get its day.

UCS banner at the People’s Climate March in New York City, 20 September 2014. SOURCE: Kate Cell, UCS.