In the midst of a pandemic that has brought the world to its knees, the Trump administration’s latest spate of anti-environmental actions is maddening—and seemingly inexplicable.

Earlier this month, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) refused to strengthen inadequate standards for industrial soot pollution even though it contributes to tens of thousands of premature deaths annually and new research shows that COVID-19 causes a significantly higher death toll in areas with only slightly higher levels of fine particulate matter.

The EPA also recently announced an unprecedented enforcement holiday for industrial polluters and rolled back fuel economy standards for cars and light trucks, which will increase air pollution and cost consumers at the pump.

There’s a simple explanation for these actions: While attention is fixated on fighting the pandemic, the administration is taking advantage of the situation to further reward the oil industry. We know that’s the case because ever since it took office, it has been diligently implementing dozens of regulatory “reforms” recommended by the American Petroleum Institute (API), the oldest and largest US oil and gas industry trade association.

API’s ‘once-in-a-generation opportunity’

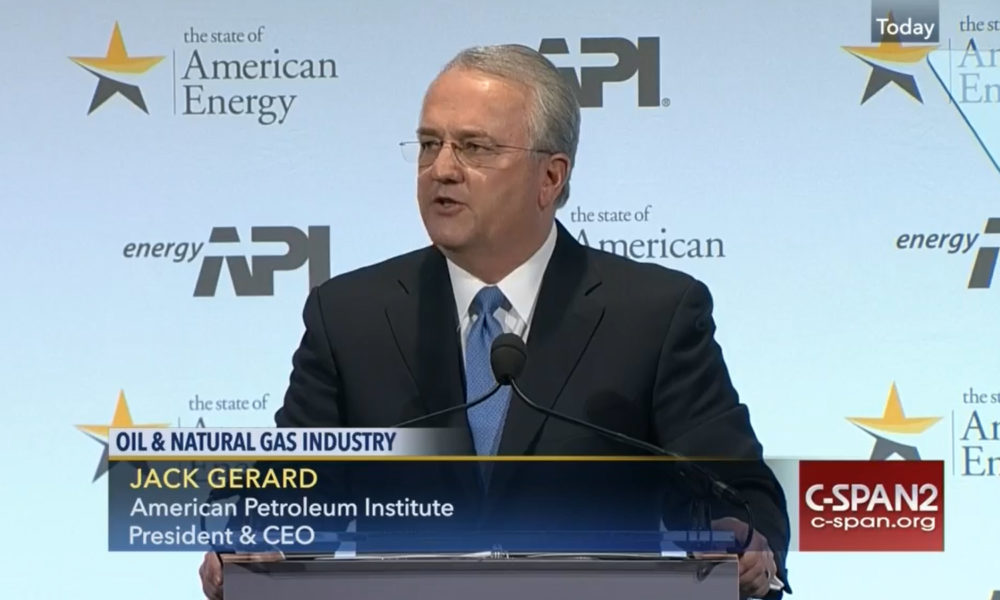

The story begins when then-API President and CEO Jack Gerard delivered his annual “State of American Energy” speech two weeks before Trump’s inauguration. After years of fighting a rearguard action against the Obama administration, Gerard welcomed “the opportunity to change the national conversation” about energy policy.

“We have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to find solutions for many of today’s most pressing issues…,” he said. “And for all of these goals, and others, the 21st century American energy renaissance”—the boom in US oil and gas production—“offers solutions.”

To ensure Trump’s unwavering support for that renaissance, the oil and gas industry rushed to fill his inaugural committee’s coffers. The committee ultimately raised a record $107 million, twice as much money as any previous inauguration, and at least $10 million came from coal, oil, and gas companies and their executives.

The oil and gas companies that donated to the inaugural included API members BP and ExxonMobil, which each gave $500,000, and Chevron, which gave $525,000. Industry executives who chipped in included API-member Hess Corporation’s CEO, John Hess, who donated $1 million, and API-member Energy Transfer Partners’ CEO, Kelcy Warren, principal owner of the Dakota Access Pipeline, who gave $250,000.

The oil and gas industry also took care of its friends in Congress. Nearly 90 percent of the $64 million it spent on congressional candidates and parties during the 2016 election cycle went to Republicans—virtually the same percentage it gave to the GOP in every election cycle over the last decade—and it spent more than $16 million on political action committees (PACs).

A month after taking office, Trump issued an executive order directing federal agencies to identify regulations to roll back, replace or eliminate, and solicit recommendations from trade associations and other stakeholders. In response, API sent a letter to the EPA with an attachment citing more than 60 environmental rules it wanted the agency to trash.

API’s wish list provided a blueprint for much of what has happened since. For instance, the EPA heeded the API’s request by:

- Weakening standards for methane, a global warming pollutant that is significantly more potent than carbon dioxide;

- Replacing the 2015 Waters of the United States rule with one that will allow pesticides and other industrial chemicals to pollute streams, wetlands and groundwater; and

- Stacking its Clean Air Scientific Advisory Panel with industry-friendly members, who erroneously concluded that the agency’s current particulate matter standards protect public health.

The list goes on. By the end of last year, the administration had either completed or was in the process of rolling back 95 environmental rules and regulations. Twenty-seven of the 58 completed rollbacks—nearly half—and 13 of the 37 still in process directly benefit the oil and gas industry. Many were explicitly requested by API.

Big Oil’s behind-the-scenes pandemic machinations

For the oil and gas industry, the pandemic offered an opportunity to press for even more concessions.

On March 23, API sent the EPA a 10-page letter asking for a temporary waiver from 28 “non-essential compliance obligations,” including monitoring and reporting pollution, because “there may be limited personnel capacity to manage the full scope of the current regulatory requirements” due to the pandemic.

The Trump administration quickly complied. Just three days later, the agency issued a memo that not only provided waivers for nearly all of the categories API listed, but also granted an unprecedented enforcement holiday for all industrial polluters. The memo said the agency did not expect any power plants, factories or other companies to comply with environmental standards or report their toxic air and water emissions for the time being and that it would not fine companies if they violated the rules.

Then, on March 31, the EPA and the Department of Transportation (DOT) issued their final rule to roll back Obama-era vehicle fuel efficiency and emissions standards. The new rule will require automakers to increase average fuel economy by only 1.5 percent per year after 2020, despite the fact that they have been complying with the existing standards, which have already saved US car and light truck owners more than $100 billion at the pump.

If the rollback survives court challenges, US drivers will pay more to pollute more. The price of a new vehicle without advanced fuel economy technology and design could be as much as $1,000 cheaper, but without those features, car owners would have to pay more than $1,400 more for gasoline over the life of their vehicles—a net loss. Less-efficient 2020 through 2026 model year vehicles would burn an additional 2 billion barrels of oil over their lifetimes, according to the EPA’s own calculations. That extra oil would mean a lot more pollution, yielding at least 867 million metric tons of additional carbon dioxide, the primary cause of climate change, and more than 170 additional tons of smog-forming volatile organic compounds and nitrogen oxides.

The oil industry’s dirty fingerprints

API’s fingerprints also are on the EPA’s fuel efficiency standard decision. API funded two fringe statisticians that President Trump’s first EPA administrator, Scott Pruitt, appointed to the agency’s Science Advisory Board, to produce studies disputing the indisputable link between air pollution and premature death. The Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers cited their dubious research in comments it submitted to the EPA in support of rolling back the fuel economy rules.

The American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers (AFPM), a smaller industry trade group, was even more directly involved in prodding the administration to allow cars to pollute more. Besides meeting with White House officials to make its case, according to a New York Times investigation it mounted a covert campaign to weaken fuel efficiency standards in collaboration with API-member Marathon Oil, the nation’s largest refiner; libertarian groups financed by billionaire refinery owner Charles Koch; and the American Legislative Exchange Council, a corporate-funded lobby group that drafts sample pro-industry bills for state lawmakers.

AFPM’s underhanded tactics included creating a phony front group called Energy4US to place ads on Facebook encouraging the general public to write to the government in support of a weaker fuel economy rule. The ad linked to a sample letter to email the EPA and DOT during a 60-day public comment period. More than a quarter of the 12,000 comments DOT made public included language that was identical to the sample Energy4US letter.

A sorry legacy

This particular chapter of the oil industry’s grip on federal policy may have started with Gerard’s “State of American Energy” speech ahead of the Trump inauguration, but as the Center for Public Integrity pointed out in a three-part series in December 2017, API has been playing a key behind-the-scenes role in Washington going back to its founding in 1919. Although its power fluctuates depending on who occupies the White House and which party controls the Senate and House, it has helped stymie congressional action on climate change (which it knew posed a threat as early as 1959) and has successfully lobbied for gutting environmental safeguards that have been in place for decades.

A majority of Americans do not support API’s agenda. Nearly 70 percent believe the federal government is not doing enough to protect water and air quality or reduce the impact of climate change. But the majority of Americans do not bankroll political campaigns and super PACs or spend tens of millions of dollars annually to lobby on Capitol Hill.

Certainly, we’ve seen something like this before. In January 2003, veteran reporter Mark Hertsgaard appraised the George W. Bush administration’s abysmal environmental record after its first two years in office. “Suffice it to say…,” he wrote, “no administration since the dawn of the modern environmental era 40 years ago has done more to facilitate degradation of the ecosystems that make life on Earth possible.”

Until now, that is. Although President Trump has repeatedly declared “I want clean air, I want clean water,” he has surpassed Bush in dismantling commonsense environmental protections, largely at the oil industry’s behest. And as long as the US political system remains awash in petrodollars, API and the giant corporations it represents will continue to dictate government policy at the expense of public health and the environment.