The 2020 Democratic Party Platform declared the previous administration’s new nuclear weapons “unnecessary, wasteful, and indefensible.” President Joe Biden has long opposed new nuclear weapons and supported reducing the size of the nuclear stockpile. But you’d never know it from the Department of Energy’s recently released FY22 budget request for the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), the agency responsible for developing, producing and maintaining nuclear warheads and bombs.

This request fully funds all the nuclear weapons the Trump administration proposed and sets funding for the nuclear arsenal slightly above the huge budget from last year. This is disappointing given that the United States already has many more nuclear weapons than it needs and scientific analysis shows the lives of those warheads remaining in the stockpile can be extended. Extending the life of existing warheads would eliminate the need to produce, at great cost, new plutonium pits, as the current plan requires.

So far, however, the Biden administration has not chosen the more conservative route, instead continuing to err on the side of excess. Specifically, the FY22 budget request funds a provocative new submarine-launched, nuclear-armed cruise missile. It funds the new W87-1 warhead for the proposed Ground Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD)—an unneeded new intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) program. It supports the excessive and unachievable requirement to achieve a capability to produce 80 plutonium pits for nuclear weapons each year beginning in 2030. It even increases funding for the B83 bomb, a massively destructive and unnecessary weapon the Obama-Biden administration planned to retire.

Ramping up spending on the W87-1 Warhead for Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent

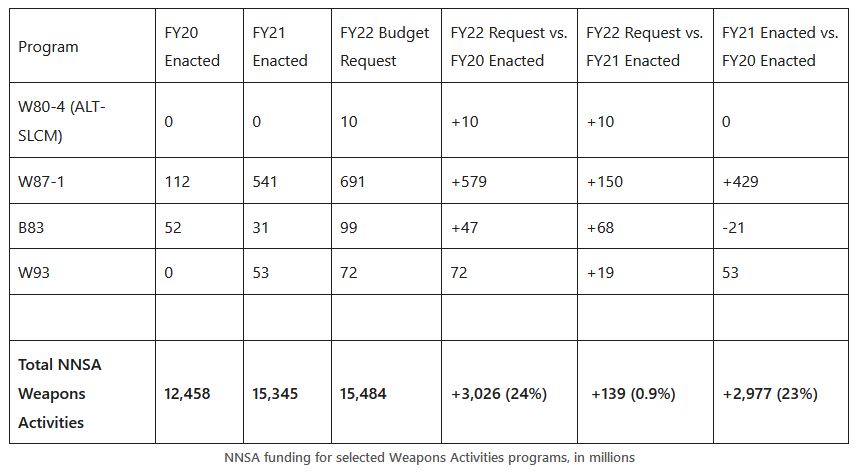

One program seeing a big increase in the FY22 budget request is the W87-1 intercontinental ballistic missile warhead. The W87-1 is planned to replace the W78 warhead deployed on the Minuteman III silo-based ICBM. The new warhead will be deployed on the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent missile, a new ICBM that is supposed to begin replacing the Minuteman III in 2029. The W87-1 program has been ramping up in recent years, jumping from $112 million in FY20 to $541 million in FY21 and $691 in the FY22 request.

There are serious questions about the need for a new ICBM, and many experts, including my colleagues at UCS, have recommended instead eliminating the ICBM leg of the US nuclear triad entirely. This would save money, which is nice, since modernizing the US nuclear arsenal is predicted to cost well over $1 trillion over the next 30 years.

To put this in perspective, $1 trillion could pay off half of all student loan debt and provide free public college tuition for four years with money left over. (And if you have different priorities, the Future of Life Institute has a great calculator that shows what else you could do with $1 trillion—it’s kind of a lot, it turns out.)

But, more importantly, eliminating ICBMs would also reduce the risk of nuclear war caused by the outdated policies that go along with these weapons, especially the unnecessarily dangerous policy of keeping them on hair-trigger alert. ICBMs are kept on hair-trigger alert because they are vulnerable to attack, but that status also greatly increases the chance of an accidental or mistaken nuclear launch by the US president, who has the sole, unchecked authority to start a nuclear war.

Even if the Biden administration is not ready to eliminate ICBMs, extending the life of the Minuteman III would be a cheaper alternative than building an all-new ICBM now, and would allow the chance to reassess the need for a new ICBM in the future, when more information is available. Pushing ahead with significant spending on the W87-1 may make it harder to back away from this program and the GBSD later on, after the Biden administration has had a chance to take a more in-depth look at whether it is even needed. Moreover, the W87-1 is a big part of the reason that the NNSA needs to produce new plutonium pits, a project that has plenty of its own problems, as discussed below.

Sea-Launched Cruise Missile continues to move forward

The FY22 budget includes $10 million to begin a feasibility study for the W80-4 warhead for a new Sea-Launched Cruise Missile (SLCM), a program initiated by the Trump administration. Nuclear sea-launched cruise missiles were withdrawn from service by President H.W. Bush in 1991 as the Cold War ended, and in 2010 President Obama ordered the retirement of the last of these missiles.

The Trump administration reinstated a SLCM program, arguing in their 2018 Nuclear Posture Review that it is needed to “provide a needed non-strategic regional presence” in Europe and Asia and “[contribute] to deterrence and assurance of allies, especially in Asia.” A June 4, 2021 memo from Acting Secretary of the Navy Thomas Harker on FY23 programs includes the item “Defund Sea-Launched Cruise Missile—Nuclear development efforts.” Both Harker and others in the Department of Defense have since backed away from this, saying that the memo was simply a preliminary, internal document, and that decisions about the program will not be made before the Biden administration’s Nuclear Posture Review. But the item’s inclusion is another indication that the Navy is not especially interested in pursuing the new weapon.

President Biden previously said that low-yield nuclear weapons were a “bad idea” and that having them makes the United States “more inclined to use them.” During the Trump administration, the US deployed a low-yield warhead, the W76-2, that is carried by the Trident D5 submarine-launched ballistic missile. While it is not yet clear what the yield of a new SLCM would be, it has been strongly implied that it would also be a low-yield weapon. But even if it is not, adding a sea-launched cruise missile to the mix is unnecessary and will only increase the danger that conventional conflicts could escalate to the nuclear level. Indeed, increasing US nonstrategic nuclear weapons add to the spiraling nuclear arms race with Russia and China, without contributing to US or allied security.

Still pretending 80 pits per year makes sense

The new budget also retains the plan to begin to produce annually 80 plutonium pits—the core of a nuclear weapon—by 2030. There is no clear rationale for the number 80, given that an independent study has shown minimum pit lifetimes to be more than a century, and further study with additional aging data may show that it is longer.

But even if there were a good reason for the number, the plans to get there have always been almost laughably unrealistic. A 2019 independent study of the NNSA’s pit production plans concluded that “eventual success of the strategy to reconstitute plutonium pit production is far from certain.” The study concluded that the 80 pit per year goal was “potentially achievable given sufficient time, resources, and management focus, although not on the schedules or budgets currently forecasted…”

The only existing pit production capability in the United States is at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico. (The previous pit production plant at Rocky Flats was shut down by the FBI and EPA in 1989 due to severe environmental damage). Los Alamos produced a total of 31 pits between 2007 and 2013, but no more since. To go from zero to 80, the current plan calls for Los Alamos to produce 30 pits per year while the Savannah River Site in South Carolina produces the remaining 50. But the budget request itself states that “based on information developed to support the CD-1 [Critical Decision-1] milestone, NNSA has determined that achieving the required 50 war reserve ppy [pits per year] production rate at the Savannah River Site in 2030 is not likely…” And in a recent Congressional hearing on the request, Charles Verdon, who has been kept on by the Biden administration as acting NNSA administrator, said that with the Savannah River Site facility up to five years behind schedule, “we assess that meeting the 2030 [deadline]…is not going to be achievable.”

Nevertheless, the FY22 budget request includes a significant increase in funding for pit production—$2.07 billion—building on another large increase last year. $603 million of this is to go to the Savannah River Site. That site is where a failed project to produce mixed oxide (MOX) fuel for nuclear reactors was abandoned after billions had already been spent, and the unfinished building is now to be turned into a pit production facility. In 2018, the NNSA estimated the cost of the facility at $4.6 billion, but the current budget requests puts it at $11.1 billion—more than double. And this is with the design just 30% complete; previous experience with large NNSA projects indicates that the actual cost will only continue to climb.

The Biden administration needs to take a closer look at the entire plan for producing plutonium pits. It should call for further study to better understand the lifetime of existing pits and should stay away from developing and producing new types of warheads that require new pits. There is no reason to require production of 80 pits per year to maintain the US arsenal and plans to reach this rate are virtually certain to fail, ending in further delays and yet more wasteful spending.

Delaying retirement for the B83 bomb once again

The B83 bomb was scheduled to be retired after the new B61-12 entered service in the early 2020s, but the Trump administration decided to keep it around “at least until there is sufficient confidence in the B61-12.” Despite the fact that President Biden was part of the Obama administration, which decided to retire the bomb because of its unnecessarily high yield and redundancy, his FY22 budget did not return to this plan. Instead, the FY22 budget request increased funding above even what the Trump administration has projected would be required, to allow the NNSA to begin work to extend the life of the bomb.

Back in 2019, acting NNSA administrator Charles Verdon, said that the maintenance and surveillance measures being performed could keep the B83 in the active stockpile for 5-7 years, but after that the bomb would need a full life extension program. In June 2020, the Nuclear Weapons Council decided to undertake such an extension. The FY22 budget includes nearly $99 million for the B83 to begin activities associated with this extension—more than triple the FY21 appropriation of $31 million. This funding will be used to begin replacing limited-life components like neutron generators and tritium reservoirs and developing a Joint DOD/NNSA Test Assembly program.

The Biden administration should reconsider and return to the original plan to retire the B83. The B83, with a yield of 1.2 megatons, is by far the most destructive weapon in the US arsenal, roughly 100 times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Air Force General Robert Kehler, at the time commander of US Strategic Command, cited its high yield as one of the bomb’s “shortcomings.”

Continuing a life extension program for this outdated and unnecessary weapon is a waste of money and resources at a time when the NNSA is already struggling to keep up with the many other programs that were previously planned.

Use the Nuclear Posture Review as a fresh start

The one piece of good news is that it is still early for this administration, and there will be chances to undo the harm from this budget and move onto a path leading toward Biden’s long-professed desire to reduce the threat from nuclear weapons. The Biden administration took office only a few months ago, in the midst of a deadly pandemic, economic devastation, racial injustice, and an urgent climate crisis that have taken attention away from even such an existential issue as nuclear weapons. The FY22 budget was prepared mostly by the existing bureaucracy while Biden’s people were still being put into positions, and the administration had little time to get up to speed. Thus, it is mostly a rehash of last year’s budget. It does not even include 5-year budget projections for each program, which are usually part of the material that is released with the request.

But understanding that there may be justifications for the current budget request does not lessen the disappointment that an incoming administration that claims a vision to reduce dependence on nuclear weapons has instead presented a budget that continues the nuclear arms race already sharply accelerated by its predecessor.

As Biden himself said in 2017, at the end of his vice presidency, “If future budgets reverse the choices we have made—and pour additional money into a nuclear buildup that harkens back to the Cold War—it will do nothing to increase the day-to-day security of the United States and our allies.” The Biden administration now needs to step up and use the upcoming Nuclear Posture Review and future budgets to carry out the substantive changes they committed to while campaigning.