In March the Department of Energy released its FY20 budget request for the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), which is responsible for developing, producing and maintaining US nuclear warheads and bombs.

(Source: Flickr)

The request outlines NNSA’s planned activities through FY24, including for weapons that have been part of the plan since the Obama administration such as:

- The life extension program (LEP) for the W80-4 warhead, which will be used with the new air-launched cruise missile—the Long-Range Standoff Weapon (LRSO)

- Producing W87-1 warheads to replace the W78 warheads on US land-based missiles

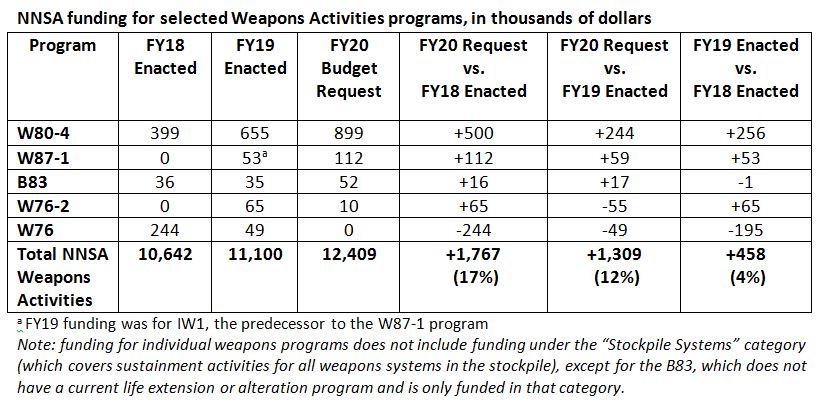

The costs of these programs are growing as they move forward with development and, as expected, have led to a substantial increase in the FY20 budget request for Weapons Activities. This category jumped almost 12%, to $12.4 billion, from $11.1 billion in FY19.

Although the Trump administration plans to add two new warheads to the arsenal—the W76-2 “low-yield” Trident warhead and an as-yet unnamed warhead for a planned new sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM)—their impact on the FY20 budget is very small. This is because the W76-2, which is nearly complete, requires only a relatively minor modification to existing W76 warheads, and the SLCM is still in the earliest stage of development, receiving only minimal funding for studies.

Big increase: W80-4 warhead for new air-launched cruise missile

The largest funding increase is for the life extension program for the W80-4 warhead that will be used with the Long-Range Standoff Weapon (LRSO), which is planned to replace the current air-launched cruise missile (ALCM). The NNSA has requested almost $900 million for the program in FY20—more than $240 million over last year’s funding of $655 million, a jump of more than 35 percent. This is on top of another large increase last year to speed the program up so that it was keeping pace with the schedule for the LRSO.

As we have previously detailed, the LRSO is an unnecessary and destabilizing weapon. It is expected to be significantly more capable than the existing ALCM, featuring enhanced accuracy, longer range, and greater speed; it will also be harder to detect. Like the W76-2 low-yield warhead discussed below, the supposed advantages of the LRSO lean more toward nuclear warfighting than deterrence.

Last year’s budget predicted that the NNSA would need only $714 million for the program in FY20. The program completed a required Weapon Design and Cost Report in December 2018 that reportedly provided data that led to the increase. In March, the Nuclear Weapons Council (a joint Department of Defense and Department of Energy group that oversees plans for nuclear weapons programs) approved the program to move into its next stage, Development Engineering. Costs for this program have increased substantially over time, and as it moves further along its development trajectory the budget will only continue to increase.

Another big increase: the W87-1 warhead for land-based missiles

Another recipient of substantially increased funds in the FY20 budget request is the replacement for the W78 warhead deployed on Minuteman III intercontinental-range ballistic missiles (ICBMs). The planned replacement will be a modified version of the W87 warhead already deployed on ICBMs—dubbed the W87-1. Its FY20 budget comes in at $112 million—more than double last year’s funding of $53 million. This warhead is slated to be fielded on the “Ground-based Strategic Deterrent” missiles which are to replace the current Minuteman missiles beginning in 2029. The warhead was previously planned as the first of three interoperable warheads (IWs) to be used on both land- and submarine-based missiles.

The IW-1 warhead was intended to replace both the W78 and half of the Navy’s W88 warheads. But the program was not supported by the Navy and experts (including my colleague Lisbeth Gronlund) raised serious questions about its high cost, increased risk, and limited benefits, leading to its eventual death. The NNSA’s FY2019 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan, released last fall, finally dropped the IW designations altogether in favor of “W78 replacement warhead” (now the W87-1), “ballistic missile warhead Y” (BM-Y, formerly IW2), and “ballistic missile warhead Z” (BM-Z, formerly IW3).

Coming in under cap: Weapons Dismantlement and Disposition

Funding for Weapons Dismantlement and Disposition is capped at $56 million per year until FY21 due to provisions in the FY17 and FY18 National Defense Authorization Acts. This was a result of opposition by the Republican-led Congress to the Obama administration’s announcement at the 2015 Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty review conference that it planned to accelerate weapons dismantlement, in part to help demonstrate US commitment to nonproliferation and disarmament. In its first year, the cap resulted in a cut of almost 20% to President Obama’s request, effectively undercutting the plan.

For FY20, the NNSA has requested $47.5 million for Weapons Dismantlement and Disposition, $8.5 million less than the $56 million the category received in FY18 and FY19. Last year’s budget request indicated that the NNSA planned to continue requesting the full amount through FY23, the last future year included. The NNSA says that the decrease this year is because of a “reduction in legacy component disposition and CSA activities.”

The FY20 budget request, like the FY19 budget request, also does not reiterate the goal of dismantling all weapons retired before FY09 by FY22, which was set out in previous budget documents. Dismantlement competes for space and personnel with weapons production programs, so it seems likely that adding on to and speeding up the production schedule will keep dismantlement as an also-ran for the upcoming crunch period for NNSA.

Delayed retirement: the B83 bomb

Also getting an increase over estimates in previous budgets is the B83 bomb which, with a yield of 1.2 megatons, is by far the most powerful weapon in the US arsenal. The B83 was previously scheduled to be retired after the new B61-12 entered service in the early 2020s, but the Trump administration has decided to keep it around for an undetermined period, confusingly characterized in some places in the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) as “at least until there is sufficient confidence in the B61-12 gravity bomb that will be available in 2020” and in other places as “until a suitable replacement is identified.” This means that it requires more funding for upkeep and increased surveillance activity to ensure it will remain usable.

According to Charles Verdon, NNSA’s Deputy Administrator for Defense Programs, these measures will be sufficient to keep the B83 in the active stockpile for the next 5-7 years, but after that the bomb would need a full life extension program, and the NNSA does not yet have an estimate for how much that might cost. Chances are that the NNSA does not want to undertake such a program, given how many other life extension programs it already has on its plate.

It would also be costly and unnecessary. Recognition that the high yield of the B83 is not needed was part of the NNSA’s argument in favor of a major life extension program for the B61 bomb, which will produce a new variant, the B61-12. In response to questions from Congress about the need for the new bomb, when the B83 can already carry out some of the same missions for which it is designed, Air Force General Robert Kehler, at the time commander of US Strategic Command, characterized its “very high yield” as one of its “shortcomings.” The B61-12 will include a new guided tail kit that will significantly increase its accuracy, and more recent reports show that it will also have earth penetrating capability. These improvements will allow it to be used against a broader set of targets, even those which may previously have required higher yield.

New: Next ICBM Warhead, Sea-launched cruise missile

New in this year’s budget are the introduction of a line item for the “Next Strategic Missile Warhead Program” and funding for a study of President Trump’s proposed sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM).

The warhead labeled BM-Y in the most recent Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan has apparently now been updated to the Next Strategic Missile Warhead (or possibly the Next Navy Warhead, as it is given different labels on different pages of the budget request). The Next Strategic Missile Warhead would eventually replace the W87 warhead on the Air Force’s planned Ground Based Strategic Deterrent missiles. Previous plans called for this to be the second of three planned interoperable warheads, to be designated IW2. In those plans, IW2 would also have replaced the remaining half of the Navy’s W88 warheads. The NNSA has not requested any funding for the Next Strategic Missile Warhead program in FY20, but indicates that it will begin to request funding in FY23 to conduct feasibility studies.

The Trump administration’s 2018 Nuclear Posture Review called for the development of a new sea-launched cruise missile, after President Obama retired a previous version in 2010. The FY20 funding is for a study called an “analysis of alternatives,” one of the earliest steps in developing a new weapons program. It is unclear how much is being requested, but according to the Arms Control Association the number is, “as much as $12 million.”

Complete: The Life Extension Program for the W76 warhead

The NNSA’s budget request for the W76 LEP drops to zero in FY20, indicating that the program is now complete. The NNSA announced in January that it had completed the upgrade of all W76s to W76-1s in December of last year. The program began production of the life-extended warheads in 2008 to extend the life of the warheads by 20 years.

Nearly complete: The W76-2 warhead

The FY20 request includes $10 million for the W76-2, a variant of the 100-kiloton W76 warhead modified to have a lower yield of about 6.5 kilotons. The warhead, the most rapidly developing outcome of the Trump administration’s 2018 NPR, is intended to replace some of the existing W76 warheads and be carried on Trident missiles launched by US submarines.

The Trump administration claims that the United States needs this weapon to respond to what it believes are increased threats from Russia and others. But as we have detailed in our fact sheet on this program, this argument does not make sense. Despite what the Trump administration says, there is no “gap” in US deterrence capabilities– existing US nuclear weapons already cover a range of yields from 0.3 kiloton to 1.2 megatons. Moreover, the W76-2, like the LRSO, will add to US capabilities for nuclear warfighting, blurring the line between conventional and nuclear conflicts and increasing the chance that a nuclear weapon could be used.

The W76-2 program received $65 million in NNSA funding in FY19, plus another $23 million from the Department of Defense. The decrease in the FY20 request is because production of the modified warheads is scheduled to be completed by the end of FY19, leaving only minor close-out activities for FY20. The NNSA announced in late February that it had completed the first production unit of the W76-2 and was on track to complete the rest of the warheads and deliver them to the Navy by the end of FY19 in September. Thus, if Congress does not step in quickly, the United States will begin deploying a destabilizing new nuclear weapon in the very near future. Fortunately, Rep. Adam Smith, the chair of the House Armed Services Committee, has already announced he is “unalterably opposed” to the W76-2 and he will likely seek to end funding for the program and bar deployment of it. His effort has the support of more than 40 former senior officials who last year recommended that Congress cancel the program.