Among the general craziness of the 2016 presidential campaign, you can be forgiven if you missed one particular crazy piece of information: the president of the United States currently has the authority to order the launch of nuclear weapons without input from anyone. This has actually been the case for decades, but the campaign brought it to the attention of the general public, many of whom were hearing it for the first time and were understandably surprised, and even somewhat alarmed, at the idea.

Moreover, the president’s sole authority holds even if he is ordering a first strike—an attack that is not in response to a nuclear attack on the United States or its allies, but rather the first use of nuclear weapons, either in an ongoing conflict or to initiate a new one. This last case may be extremely unlikely, but there is currently no law that rules it out.

As former Vice President Dick Cheney said in a 2008 interview, the president “could launch the kind of devastating attack the world has never seen. He doesn’t have to check with anybody, he doesn’t have to call Congress, he doesn’t have to check with the courts.”

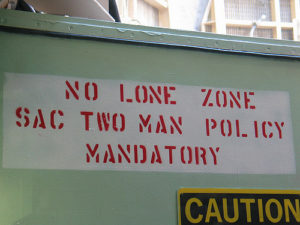

The usual policy for working with nuclear weapons requires that two people be present and in agreement before undertaking any procedure. The president should not be exempt from this rule when deciding to launch a first strike. Photo: mako

If, like me, you think this situation makes no sense, then there is some good news—Senator Ed Markey (D-MA) and Representative Ted Lieu (D-CA) are trying to change it. They recently introduced the Restricting First Use of Nuclear Weapons Act of 2017, which would prohibit the president from launching a first nuclear strike without a declaration of war by Congress. This common-sense step would prevent the president, the sole individual with the authority to launch U.S. nuclear weapons, from single-handedly starting a nuclear war.

While the 2016 campaign may have been the catalyst, the underlying problem is independent of who is in office. No single individual should have the authority to launch a nuclear war without extensive discussion, debate, and consideration of all the possible implications. As former Secretary of Defense William Perry has said, “a decision that momentous for all of civilization should have the kinds of checks and balances on Executive powers called for by our Constitution.”

Check out our fact sheet available on the Markey-Lieu bill, or read on for more information on why it is so important.

Current Situation

As it stands, the president could wake up tomorrow and simply notify the military that he had decided to order a nuclear strike. There is no requirement that he consult with anyone. He could choose to talk to advisers first, but whether or not he did, no one could stop him if he decided to go forward.

Once he made his decision, the president would use a card, often called the “biscuit,” that he or an aide carries at all times, to read a code to authenticate his identity to the senior officer on duty in the Pentagon’s “war room.” The war room would then prepare the order to send to launch crews on submarines and at command centers for land-based missiles. The time from when the president gives the launch order to when the crews receive it would be only minutes. Land-based missiles would be launched within about five minutes of the president’s order, while it might take about fifteen minutes for submarine-based missiles to launch. And once launched, these missiles cannot be recalled.

In 1974, President Richard Nixon—the last president to draw attention to the significant downsides of this system—noted, “I can go back into my office and pick up the telephone and in 25 minutes 70 million people will be dead.” Later that year in the thick of the Watergate scandal Nixon was emotionally unstable and drinking heavily, leading Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger to instruct the Joint Chiefs of Staff that “any emergency order coming from the president”—such as a nuclear launch order—should go through him or Secretary of State Henry Kissinger first. Schlesinger had no real authority to do so, however, and it is not clear what might have happened if such an order had actually come. The same would be true today—there is still no military or civilian official or group with the authority to countermand a presidential order to launch nuclear weapons.

What Would the Bill Do?

The Markey-Lieu bill states that “Notwithstanding any other provision of law, the President may not use the Armed Forces of the United States to conduct a first-use nuclear strike unless such strike is conducted pursuant to a declaration of war by Congress that expressly authorizes such strike.” The bill defines a first-use nuclear strike as “an attack using nuclear weapons against an enemy that is conducted without the President determining that the enemy has first launched a nuclear strike against the United States or an ally of the United States.”

Why Does the President Have Sole Authority?

The main reason the president has had sole authority to launch a nuclear strike is the perceived need to ensure a swift response to an incoming nuclear attack. During the Cold War, U.S. leaders feared a “bolt from the blue” attack by the Soviet Union, which could destroy US land-based missiles if they were not launched quickly. A decision about whether to launch a retaliatory strike would need to be made in the ten minutes or so between the time the incoming attack was detected, data analyzed and conveyed to the president, and when the missiles landed.

The nuclear command system was therefore designed for speed rather than deliberation. Its main purpose was to allow the president to launch U.S. nuclear weapons quickly, before they could be destroyed on the ground. This was always dangerous, and has long been unnecessary as well, since the U.S. has submarine-launched missiles that are invulnerable to such an attack and ensure that the U.S. can maintain a deterrent. UCS believes that the United States should end this risky practice by removing its land-based missiles from hair-trigger alert and eliminating rapid response options from its war plans.

However, until the president and the military agree to end these prompt launch options, the Markey-Lieu bill does not affect them. It also intentionally and specifically does not restrict the president’s ability to immediately order the use of U.S. nuclear weapons in response to a nuclear attack.

The situation the bill addresses is the decision to launch a first strike—when the United States is the first to use nuclear weapons against an adversary. In this case time constraints on decision making do not apply, so the streamlined decision process that might be needed in a retaliatory strike is not required. Regardless of whether the decision is to unleash a nuclear first strike as the first move in a conflict, or to use nuclear weapons first in escalating an ongoing conflict, the president would have time to consult with advisers and Congress before making such a potentially world-altering decision.

A Nuclear First Strike Is an Act of War

Make no mistake about it, as the bill states, “By any definition of war, a first-use nuclear strike from the United States would constitute a major act of war.” Nuclear weapons have unparalleled destructive power; their use would break a taboo of more than seventy years. The Constitution clearly establishes that the power to declare war belongs to the Congress alone. Therefore, this bill simply makes explicit an existing Constitutional requirement on the president.

Moreover, bringing Congress into the process would lessen the chance that such a decision could be made irrationally or impulsively. The decision to use nuclear weapons is potentially the most important decision this nation could make, with grave consequences for every citizen of the United States and the world. A decision to use them first should be undertaken only with the utmost caution and—especially in a democracy—should not be left up to any single individual.