This past weekend, I had the honor and challenge of presenting at the Fifth Annual Climate Conference of the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). For the past three years, UCS has been proud to be one of the sponsors of this summit at Dillard University, in New Orleans, and we’re looking forward to continuing to support it in years to come.

For me personally, this year’s event took an important turn when a Howard University student stood up and posed a good, hard question: How does your whiteness inform your work on climate change?

An honor…

It’s an honor to speak to the HBCU Climate Conference.

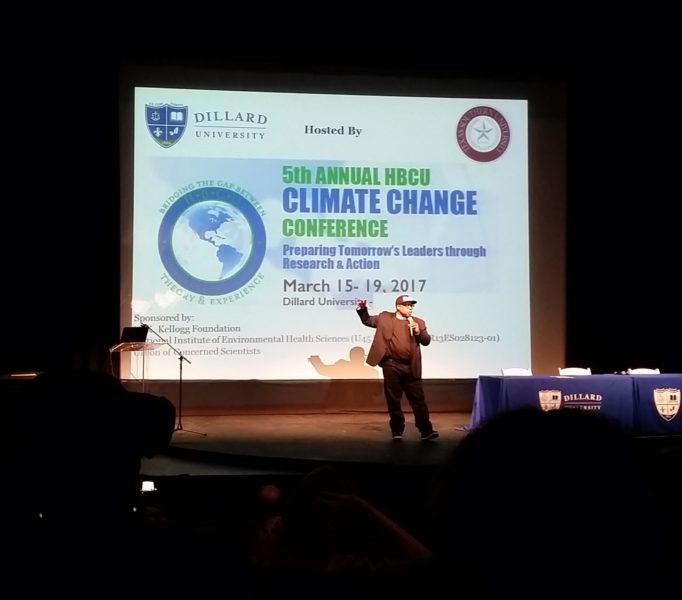

Reverend Lennox Yearwood delivering a moving keynote address to the HBCU Climate Conference. Photo: Erika Spanger-Siegfried

Its co-conveners are environmental justice luminaries, people you feel lucky to have met. Dr. Beverly Wright of Dillard University is founder and director of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice and a larger-than-life EJ scholar and voice. Dr. Robert Bullard of Texas Southern University is considered the father of environmental justice.

The conference’s speakers leave an imprint. Friday’s keynote speech, for example, was delivered by Reverend Lennox Yearwood, leader of the Hip Hop Caucus, a star in the climate movement, and a source of inspiration since I first heard him speak back in February, 2013 at the DC rally against the Keystone Pipeline. (I was so happy, I told him, when he tweeted one of my blog posts earlier this year…)

And its participants—the students, experts and activists gathered—were energized as they discussed both their studies and their activism. As Dr. Bullard described the buses of HBCU students that would be heading north to DC for the April 29th People’s Climate March, I was inspired and hopeful for the climate movement taking shape.

And a challenge

And it was a challenge for two simple reasons.

First,“green groups” have historically had a poor reputation in this community. In addition to being overwhelmingly white, groups such as the Sierra Club, the National Resources Defense Council, the Environmental Defense Fund, and UCS, among others, gained that reputation over many decades by, at best, not obviously caring about environmental justice concerns, and at worst, diverting attention from those concerns and exploiting them when advantageous.

Indeed, in his keynote address, Reverend Yearwood elicited strong, even angry agreement from the audience when he railed against these groups that, in essence, have not cared about them.

Second, I’m white. One of the many things that means is that the privileges I wear around—for much of my life, many of them unwittingly—are perfectly obvious in this setting. And it doesn’t really matter if I try to check my “invisible backpack” at the conference door; everyone knows I leave with it and that this sets me, maybe irrevocably, apart from the mostly African-American attendees. And that, if I’m totally honest, makes me uncomfortable.

Most participants at the HBCU gathering have had to become familiar with being one of just a few people of color in the crowd. The same isn’t true for most white folks; I get to be comfortable most anywhere I go.

As Reverend Yearwood spoke, however, I felt my whiteness more and more acutely. In his narrative, as a member of the environmental community I wasn’t necessarily the enemy of those gathered, but nor was I a friend. As African-American children grew up in the shadow of coal-fired power plants, breathing unhealthy air and developing childhood asthma, environmentalists from the big green groups showed up, he lamented, only when it was in their interest—e.g., as part of an effort to shut down a particular power plant.

As he spoke, I started scratching out and scribbling over my original opening remarks. I couldn’t, I realized, launch straight into our shared cause and mutual enemies in the climate fight. Before I could do anything close, I needed to make clear that at UCS we get it, or at least we’re really trying to; we’re here at this conference as part of ongoing efforts to right some past wrongs, and to support the growth and strength of the environmental justice movement on its own terms and turf.

UCS scientist Erika Spanger-Siegfried, "EJ coastal communities face special risks from flooding and rising tides" #HBCUClimateChange2017 pic.twitter.com/rIaS4Rk7qy

— Robert D. Bullard (@DrBobBullard) March 17, 2017

An excellent question

I was on an all-white panel. I gave my talk. The audience seemed engaged and people lined up to ask questions. The young woman from Howard University prefaced hers by saying “at Howard, we learn to ask the hard questions.” And she did.

Her question—how does my whiteness inform my work on climate change—was kind of the elephant in the room, she said. The whole conference was about how the participants’ blackness informed their work. What about my whiteness?

Indeed. Oddly, it was something of a relief to get this question. I had no immediate idea what to say. So I started with where I come from; with the fact that I grew up within half a mile of a coal-fired power plant; that I developed asthma as a child. I guess I was trying to say that what Rev. Yearwood was describing isn’t completely foreign to me. Or that my whiteness might mask relatable things about me or connote some privileges that I didn’t in fact have. I suppose I was just trying to humanize myself and be seen.

My parents were activists, I went on; my dad was a social justice organizer when I was small. Of the many issues we would talk about, the many things wrong in the world, climate change is the one I was drawn to. It felt like the mother of all problems; how could I not work on it?

After this, I said, is where my whiteness probably comes most into play.

I have worked on climate change for nearly 20 years. And for much of that time, I was troubled by, but didn’t engage with environmental justice issues in an active way. What would play in my head was something like: I’m a person who’s working hard on an important issue, I’m in the battle, trying to keep my head above water, and that’s enough. It’s not the only issue, I would say, but it’s a big one, and my work over here will have to do. I didn’t have to engage in environmental justice, personally, because my privileges sheltered me from most EJ concerns. And I didn’t engage in it professionally because, where I worked, we had different top priorities.

To change everything, we need everyone

What I’ve since come to see is this: that’s not how we win, any of us. There’s not my piece of the battle and your piece of the battle. There’s just the battle.

At this moment, here in 2017, many of us are losing our piece of the battle. And if we don’t join forces to win it, we’re all lost. And if we don’t come to the table with openness and willingness to engage with each other’s concerns, we won’t join forces.

I didn’t say this at the time, but I was reminded of the Peoples Climate March in New York City, back in 2014, where the motto was “to change everything, we need everyone.”And truly, it felt like everyone was there that day, marching down 6th Avenue. And as we looked around, we could feel it: this is what America looks like; this is how we change the world.

And outside of those high-profile times when we come together as a movement, we at UCS have a role to play as scientists and as allies.

Quite simply, ensuring that the concern of the Union of Concerned Scientists extends to equity and environmental justice and that, in that spirit, we show up and contribute more—that is just the right thing to do.

Good climate allies: May we know them, may we be them

It’s just the past few years that I’ve come to see this clearly. It’s a journey and I’m still on it. But I understand now that we can’t be satisfied chipping away at our issues. We’ve got to look up, see the concerns of our allies, and find ways to show up for them.

Speakers had just a minute or so to respond, and so I left it there.

There’s more to it, of course. Like the fact that my whiteness afforded me the luxury of being out in nature a lot and, through this, delivered me to the problem of climate change through a very certain door—a different door than some in the EJ community.

Or the fact that, in this battle, some of us face much greater risks than others—the low-income neighborhood that doesn’t get rebuilt after a storm, the indigenous community whose ways of life are breaking down under climate stress, the urban residents who struggle to cope as heat waves worsen. For now, folks like me are sheltered from much of this. So folks like me need to recognize that, while what we bring to the table is valuable, others are the very face of climate change.

The movement we’re seeing take shape in response to climate change is growing, necessarily, to be about more than climate change. It’s also about climate justice and jobs and social equity and human rights. And it’s only because each of those additional concerns found a place at the table that, today, we have the climate movement that we so desperately need.

I’m hanging my hopes on this movement.

I may always be one of its more privileged members. I aim to always be a fierce and hard-working one and, increasingly, a good ally.

I’ll be at the March for Climate, Jobs, and Justice in Washington, DC, on April 29. There the Peoples Climate Movement will be in the streets in all its many-faceted glory (and I do mean glory; if you haven’t marched, join UCS and others and experience for yourself). And I’ll march like I work each day: for a stable climate, for my kids, and in solidarity with the millions of folks with whom I share this common, essential cause.

If I see the Howard student there, I will thank her for sparking the good conversations I’ve had since.

And to our blog readers, please ask UCS tough questions on these issues going forward and help hold us accountable. We won’t always have a ready answer. But we will always try to do what’s right to win this fight.