This week, summer 2023 comes to a close on our calendars but will be remembered for its record-shattering extremes, notably, heat—until, that is, the next record-shattering summer supplants it, quite possibly in 2024.

Climate change smothered us in heat this season, here in the US and across much of the world, but it has not affected us as equals: some of us can stay relatively safe and cool while many of us cannot and suffer instead. With summer largely over, a priority in the coming cooler months should be to use this respite to build equitable resilience to next year’s inevitable deadly heat.

Basic inequities of keeping cool

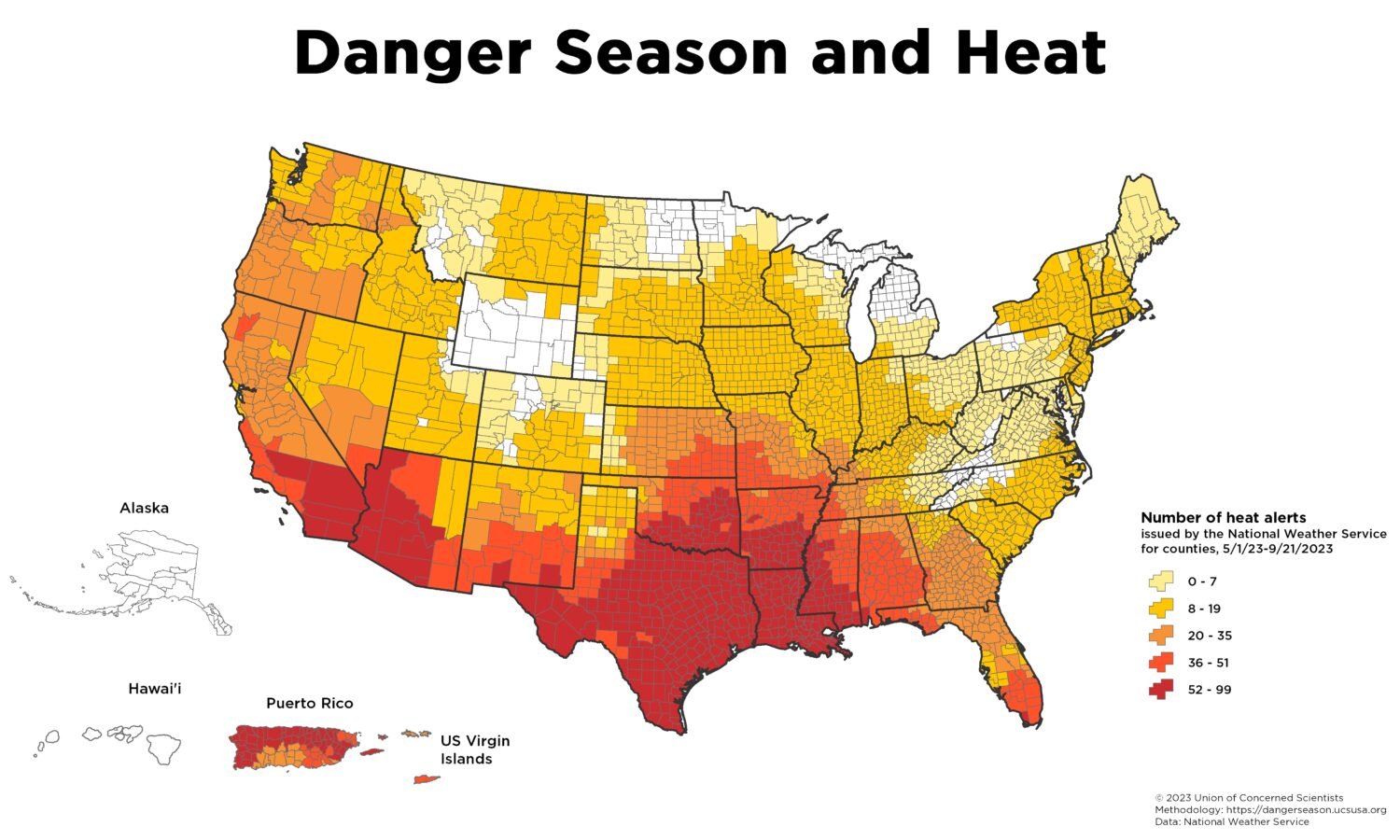

Climate change causes harm and suffering primarily by creating and exacerbating weather extremes, like extreme heat. These extremes are most acute during the warmer months of May through October—what we at UCS now call Danger Season.

Whether one can come through Danger Season unharmed depends heavily on present and historic inequities. And by acutely harming the more vulnerable among us, e.g., making us sick, preventing us from working, or damaging our homes, climate change can deepen these inequities and exacerbate this cycle.

Climate change is only accelerating, and so the threat to vulnerable people is mounting. Both forces—climate change and inequity—must ultimately be bent toward justice.

With dangerous heat a prominent feature of summer 2023 nearly everywhere in the northern hemisphere, and expected to be even worse next summer when El Nino is in fuller effect, this post outlines some of the ways in which that heat will hurt the more vulnerable among us, and flags a few of the things we can do today to counter this harm.

People working outdoors

Record-breaking heat across much of the country this summer created a formidable landscape in which working outdoors—or anywhere without access to cooling—was dangerous, even deadly. Because heat exposure exacerbates so many other medical conditions, data on heat-related illness and death severely undercounts the real impact extreme heat has on public health—yet heat is still by far the number one cause of weather-related death each year.

Despite the risks, though, outdoor workers currently have no federally-guaranteed protections from heat. As my colleague Alicia Race relays in her blog post, access to water, rest, and shade, however essential during dangerously hot days, are “not legally guaranteed for most people who work outdoors or in hot indoor facilities”. UPS employees made air conditioning in delivery vehicles a key demand in recent union negotiations—and won—but elsewhere, big corporations are lobbying against vital worker protections like these.

In the agriculture sector, most of the nation’s produce is harvested by low-paid workers; a large share of them are Hispanic and a large share (roughly half of hired crop workers) lack legal immigration status. Many of these workers are paid, not by the hour, but by the volume they pick, incentivizing exertion. Most California counties, where a huge share of the nation’s fresh produce is harvested, experienced more than a dozen extreme heat alerts this summer. In places like the Yakama Valley in Washington state, cherry pickers and other farm workers have shifted to nocturnal work schedules to avoid the daytime heat.

Much of the US South experienced a summer of heat conditions that obliterate past records. This includes Texas, where Governor Greg Abbott recently signed what’s become known as the “Death Star bill” for its blatant inhumanity. Among other things, it nullifies existing local regulations that grant outdoor workers the right to water breaks.

I suffered from heat exhaustion a few years ago after some exertion on an unusually hot spring day. I was confused and bone-tired and it felt like a bed of coals had been lodged deep in my guts, burning and overheating me from the inside.

But I had access to a cool room. I had people who brought me cold drinks. I could drop everything and sleep, which I did for hours. Now, when the temperatures soar and I see people toiling in the sun, I remember that feeling—how dangerously unwell a hot day had made my body—and think: God, I hope you can stay safe. It takes a certain gall to sit in an air-conditioned office and sign this into law while record-shattering heat sent the overworked to emergency rooms across the Sun Belt.

As we at UCS recently outlined in a call-to-action for our supporters, “A lack of federally-mandated cooling protections such as access to water, rest, and shade means workers continue to get sick or die because of extreme heat.

If we don’t act urgently on climate change, extreme heat would cause tens of millions of US outdoor workers to risk losing a collective $55.4 billion in earnings each year by midcentury, a peer-reviewed Union of Concerned Scientists analysis shows.

Even with bold action to limit heat-trapping emissions, outdoor workers would face severe and rising risks from extreme heat—and that’s why we must act now. Additionally, outdoor workers must be able to access basic, life-saving measures without fear of retaliation or docked pay. The Asunción Valdivia Heat Illness, Injury, and Fatality Prevention Act being considered in Congress will hold employers accountable to keep workers safe from extreme heat and prevent more senseless deaths.

What you can do today:

With some big businesses lobbying against heat protections, outdoor workers need widespread support. Tell your members of Congress to support and pass the Asunción Valdivia Heat Illness, Injury, and Fatality Prevention Act. One way to do so is here.

People living in prison

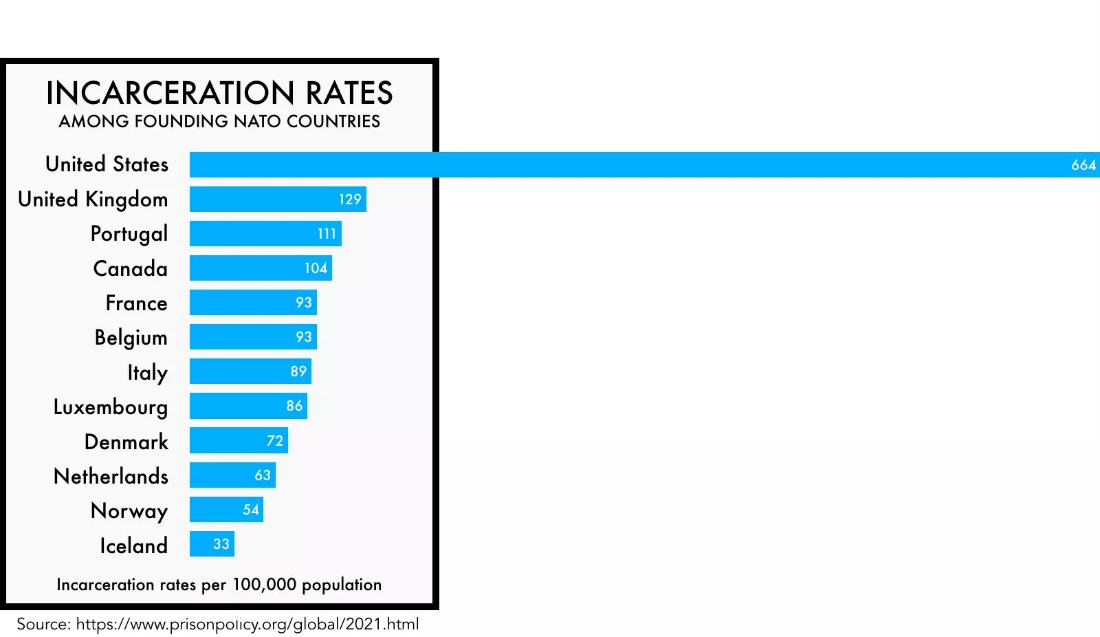

The US is the global leader in imprisonment, with roughly five percent of the world’s population but more than 20% of its imprisoned people. Black people in the US are imprisoned at roughly five times the rate of white people. In summer, it gets hot behind bars, and this summer’s heat has been torturous.

Data on the presence of air conditioning in prisons is patchy, but according to the Prison Policy Initiative, “at least 13 states in the hottest regions of the country lack universal air conditioning in their prisons: Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia”.

Most of these states rank in the top 20, nationally, for rates of incarceration. And if we look at Texas, the largest prison system in the second hottest state, one analysis finds at least 22 have no air conditioning. Most of Texas’ prisons are located in counties that were under extreme heat alerts dozens of times this summer.

Limited access to cooling for prisoners was dangerous in yesterday’s climate, but in today’s ever-hotter climate it can be like being jailed in a pre-heating oven.

In Louisiana, minors are being housed in un-airconditioned cells at Angola prison in feels-like temperatures of 120°F, conditions known to pose “extreme danger” of heat-related illness and death. And indeed, in today’s climate it’s turning deadly. Though Texas hasn’t officially recorded a heat-related prison death since 2012, analysis by the Texas Tribune suggests there have been at least 40 such deaths in this year’s heat alone, including more than a dozen prisoners in their 20s and 30s.

No one should have to suffer or face death from heat while imprisoned. People are meant to serve time, they aren’t supposed to be tortured. But this summer—and without reforms, for all summers to come— for the people locked in uncooled prisons, torture is what it can feel like.

What you can do today:

The data make it clear: our country needs reforms to its criminal justice system and the mass incarceration it has created.

Given the staggering numbers of people we have put behind bars, and the increasingly deadly summers they must survive there, we face an immediate challenge of making our prisons places where people can safely serve their sentence. In addition to supporting climate action, consider supporting prison policy reform-focused groups like the Equal Justice Initiative, the Sentencing Project, and the Prison Policy Initiative, and groups with specific state targets, like the Texas Prisons Community Advocates.

People without shelter

One of our basic human needs is adequate shelter to protect us from the elements, and with climate change, the elements are more dangerous than ever. But in the US, between 500,000 and 600,000 are estimated to be experiencing homelessness at this time, with roughly one-third of those people sleeping “on the streets” and exposed to storms, flooding, poor air quality, and this year’s deadly heat.

Phoenix, Arizona, with a surging population of unhoused people, is an epicenter of extreme heat suffering and harm this summer. The city saw 54 days with temperatures above 110 degrees and a month’s worth of nights when temperatures never dipped below 90 degrees. Unhoused people sought refuge in cooling centers and were admitted to emergency rooms with heat stroke and serious burns from exposure to scorching pavement.

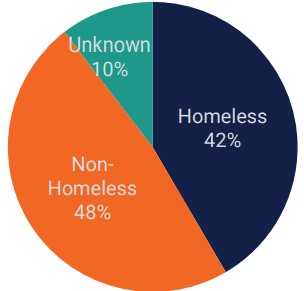

So far this year, 202 people in Phoenix and surrounding Maricopa County are confirmed to have died of exposure to extreme heat (with more than 150 others under investigation), and though unsheltered people account for far less than 1% of the County’s nearly 4.5 million people, they account for at least 42% of confirmed heat-related deaths this year.

With the end of the COVID-19 eviction moratoria, more people are becoming housing insecure or unhoused, deepening the nation’s existing housing crisis. And with climate change, much of our existing housing is being exposed as inadequate to changing climate conditions—e.g., with insufficient (and/or inefficient) cooling.

While not a panacea for homelessness, addressing the nation’s affordable housing crisis will help. It will require not just the creation of quality, affordable, energy-efficient housing, but housing that is sited and constructed to keep people safe and sheltered from climate extremes.

What you can do today:

UCS is thinking more and more about the importance of safe, affordable, resilient shelter in meeting the needs of the most vulnerable people amidst climate change. While we expand our expertise in this space, we encourage people to support organizations already heavily engaged in it.

Visit, for example, the National Low Income Housing Coalitions Action page for a list of ways to engage on the issue and urge Congress to do the right things to address our homelessness and housing crises. Look for and support local groups in your community, too, who are fighting for safe, affordable housing; the problem is everywhere.

People living in urban heat islands

More than 80% of the US population lives in cities, and this summer’s heat engulfed most of them at one point or another. Within cities, treeless urban landscapes are almost invariably the hottest areas and are more often home to low-income communities and people of color who have been historically consigned to live there.

These urban heat islands are created when the sun’s heat is absorbed by building materials like concrete and released back into the city environment, elevating both day and nighttime temperatures. In neighborhoods with less tree cover, more heat is absorbed.

One particularly dangerous effect of urban heat islands is the way they elevate nighttime temperatures. Cool nights give our bodies a chance to recover from daytime heat; when we’re deprived of this, especially over a long period of time, our risk of heat illness can increase. Extended heat in cities has also been linked to increased violence. With climate change, nights are warming faster than days.

With more extreme heat turning our cities into ovens, we should be racing to cool them—starting with the low-income and historically under-resourced neighborhoods where the heat hurts most.

What you can do today:

Encourage your federally elected officials to cosponsor legislation Sen. Sherrod Brown and Rep. Ruben Gallego have introduced in the Senate and House of Representatives respectively, the Excess Urban Heat Mitigation Act (S. 1379/H.R. 2945). This bill creates a grant program through the Department of Housing and Urban Development to provide resources to local governments to help with the effects of excess urban heat such as providing “cool pavements, cool roofs, tree planting and maintenance, green roofs, bus stop covers, cooling centers, and local heat mitigation education efforts.” Tell your electeds, we’re going to need all that and more!

And many others…

Extreme heat makes hard lives harder.

People with chronic medical conditions can face heightened risks amid heat waves. For example, the added cardiovascular strain of cooling the body can increase heart disease risks.

Those living with obesity tend to retain more body heat and can struggle more than others to stay cool.

Some medications, including those taken to treat many mental illnesses, can make it harder for the body to shed heat. Escaping the heat in a cool location can be harder for people with disabilities or mental illness, as well.

People who are elderly often fit one or more of the above profiles and are thus at higher risk, generally, than younger people to heat-related harms.

That said, young children require special monitoring in extreme heat, on the one hand because their small bodies are less efficient at cooling themselves, but also because they may not know when to regulate their activity level amid hot conditions.

Pregnant bodies, too, are less efficient at shedding heat.

Then there are the larger circumstances that make extreme heat a dangerous burden for so many of the world’s people. Whether people enduring deadly desert heat to migrate to the US, people persisting in refugee camps situated on baking marginal lands, or people hustling in oven-like urban slums around the world, there are billions of people living hard lives made painfully harder by killer heat and the other faces of climate change.

A better world

This week, the U.N. Secretary General, Antonio Guterres convened a Climate Ambition Summit, calling on the nations of the world to get serious.

Tens of thousands marched in the streets and people were arrested, all demanding an end to the fossil fuels that brought us this problem. There is an air of urgency—and increasingly, desperation—about it all.

Desperation, in part, because of the extreme heat that the climate just showed us it can generate with less than 1.5°C of average warming—and because we’re still hurtling toward much greater warming.

The vulnerable people discussed here are essentially tied to the bowsprit as we sail into this dangerous future while others of us are, for now, safer in our cabins below deck. But the whole ship will sink before long if we don’t steer a different course.

We each need to resist the madness, abhor the injustice, believe in that better world, and most importantly, get out there and act on it.