It would just be ironic if it weren’t so dangerous: Today our power sector depends heavily on water, even as its carbon emissions help drive climate change, which can make water resources harder for everyone, power sector included, to secure. Fast forward a few decades to when some of the key factors at play have grown more extreme – e.g., hotter and drier summers, more erratic water supply – and things eventually stop adding up. To have secure power and water in a warming world requires that we act smarter today. Our new energy-water report suggests how.

We’ve been water foolish

Our nation’s aging power plant fleet uses vast volumes of water for cooling. So when heat waves and drought hit the U.S. in 2011 and 2012 (and just these past weeks, in 2013), they exposed serious, widespread water-related risks in the power sector: from the Texas coal plant that required cooling water to be piped in from a distant river, to the Vermont nuclear plant that had to shut down when local water temperatures soared. And with increased heat waves and drought forecast for many U.S. regions in our climate change future, the risk of such collisions is only growing.

In a warming, water-constrained world, our long-lived, far-reaching decisions must be water smart. Today, too many power plants put pressure on local water resources directly, even as they help drive climate change and its impacts on water resources. We should seize every chance we get to fix this. (Photo credit: Flickr/LarryHB)

At the same time, with lots of aging power plants ripe for retirement, there is a huge opportunity to build a power sector fit for the 21st century. The new Water-Smart Power report from the UCS-convened Energy and Water in a Warming World Initiative (EW3) explores how different electricity choices can greatly reduce or exacerbate that risk.

Getting water smart…

By shifting to an electricity mix heavy on low-water renewables like wind and solar photovoltaics, the report finds, we can cut water use by the power sector, nationally, in half by 2025 and by 80 percent by mid-century.

In a water-constrained future, that represents smart policy for power companies: their plants are far less vulnerable to drought and other variations in water supply. But cuts like this can reverberate across water users, both today and heading in to our water-tight future.

…in the Southwest

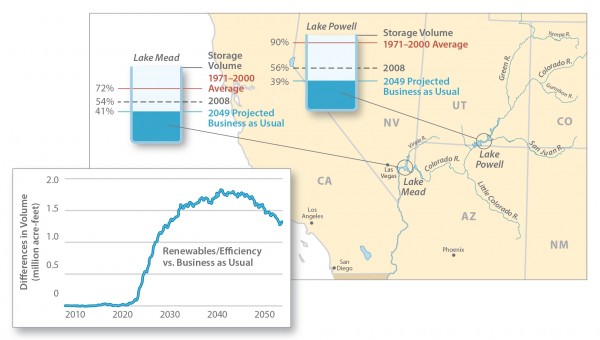

In the arid Southwest, for example, our work found that low-water electricity scenarios could yield significant savings in vitally important reservoir storage. In this typically dry region, power plants are small consumers of water compared to agriculture, but their water use can make a major difference on a cumulative basis – e.g., in the accumulation of water over time in crucial reservoirs. By 2030, the low-water renewables scenario mentioned above could essentially “free up” nearly 500 billion gallons of water to be stored in Lakes Mead and Powell.

In a region where water demand can exceed supply, and is only met by reservoir drawdowns; where drought-exacerbated wildfires can wreak havoc; and where drought and heat are projected to worsen in the decades ahead, those kinds of water savings matter. Both Lakes Powell and Mead have spent most recent years well below capacity and, with climate change and growing demand, much greater water strain is foreseen for the region. In this light, water-smart electricity choices are an absolute must.

Electricity choices can affect water storage: An electricity future that requires less water to produce power could mean that more water gets stored in Southwest reservoirs. When electricity uses less water, more is available for other users, like cities, households, agriculture, and wildlife. (See Water-Smart Power for more.)

…in the Southeast

In the Southeast, hydrology has tended toward the extremes in recent years – either very wet or very dry – and during hot, dry years, low flows in rivers and streams and high water temperatures can result. Power plants in this region take vast volumes out of rivers and streams for cooling and, while they put most of it back, it’s hotter, and some of it evaporates downstream. This water use, set against the region’s varying hydrology, has spelled trouble for some power plants and for other water users in recent years.

In an electricity future where low-water renewables and efficiency dominate, many power plants with heavy water-use habits today would be taken out of the equation, resulting in higher river flows and cooler water temperatures – cooler even than today. On the Coosa River, for example, near the Alabama-Georgia border, our modeling suggests that water temperatures would exceed 90 degrees – temperatures dangerous to many fish species – an average of six days each summer over the next decade. According to EW3’s new analysis, by the 2030s, water temperatures would stay below that 90-degree threshold all summer, even with warmer temperatures and a drought.

In a region where access to water has pitted states against one another in protracted court battles, where population is expected to grow significantly in coming decades along with demand for electricity and water, even as temperatures rise, water-smart electricity choices – those that use far less water and don’t heat up waterways – are essential.

…and beyond

A scan of the country will show stark situations and strong reasons to make water-smart decisions – to say nothing of the rest of the world, where water circumstances are dire in places and spreading.

Just last week, we received the latest reminder that our electricity system needs to break its water dependence. As a heat wave wore on across eastern states, New York broke its power usage record, and the grid in New England strained to keep up with near-record power usage. Amidst this, Massachusetts’ Pilgrim Nuclear plant had to briefly reduce its power output, in response to high water temperatures in Cape Cod Bay. The weekend came, electricity demand dropped, the heat wave broke, and a crisis was averted. But the heat will be back – hotter and longer in the years ahead. The makings of this kind of crisis are not going away. As the new report says, we can and must design them out of the system.

So, water-smart choices across the board, and only those that are low-carbon. The days when anything less passed for smart, long-term decisions are over.

Several UCS colleagues are sharing other aspects of this important new work in recent and forthcoming blogs. Please read on.