Experiencing the effects of or watching a loved one decline from relentless degenerative diseases, like Alzheimer’s and dementia, is heart-wrenching. Across the world, patients and their loved ones keep up-to-date on emerging treatments on the horizon, hoping that with the right drug, they may be able to hit the brakes on the devastating disease progression and enjoy more time doing the things they love with the people they love.

It’s indisputable that there’s a critical need to get treatments that work out to people who need them. But there’s also an important science-based process that must be followed to ensure that people aren’t given false hope or experience devastating side effects when spending thousands of dollars on these drugs.

We need to be able to trust that our government is ensuring that drugs hitting the market are safe and effective, and the benefits will outweigh any side effects or risks. We need to be able to trust that the government will follow the science and listen to its own scientists and external medical experts when making approval decisions, and not cowing to industry or political pressure.

That’s why it was big news last week when the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a new Alzheimer’s treatment—the first in almost two decades— that its own science advisors almost unanimously told the agency was not effective. This is not normal and is one in a handful of times the FDA has completely ignored its advisory committee’s rejection of a drug. The decision has already resulted in the resignation of three committee members—almost a third of the makeup of the committee.

What’s different about the Aduhelm decision?

Drugs reviewed by the FDA go through rigorous evaluation by staff scientists and are then subjected to an extra layer of review by independent advisory committees made up of researchers, medical doctors, and clinicians from external institutions who are free of conflicts of interest. As the agency accurately contends, “Their advice and input lends credibility to regulatory decisions. The Committee helps the regulatory decisions withstand intense public scrutiny.”

In fact, according to the government-run database on advisory committees, while the FDA has the option not to implement recommendations from its Peripheral and Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee, between 2003 and 2021, it fully implemented 86% and partially implemented 10% of its recommendations.

What did FDA’s science advisory committee recommend?

The drug aducanumab, marketed as Aduhelm, is manufactured by Biogen and is expected to cost about $56,000 a year. Almost as soon as the announcement hit the wires, skepticism about the evidence of this drug’s efficacy from notable scientists, including FDA’s own science advisors, began. So far, three members of the FDA’s Peripheral and Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee have resigned. This panel of 11 medical experts (9 of which are voting members) recommended rejecting its application for approval back in November after it reviewed clinical trial data.

At that committee’s most recent meeting in November 2020, its members agreed that the clinical trial data did not convincingly show that Aduhelm could slow cognitive decline in people with early-stage Alzehimer’s. Ten members voted against the drug showing effectiveness and one member was uncertain.

One of the members who submitted his resignation, Dr. Aaron Kesselheim from Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital said, “This might be the worst approval decision that the F.D.A. has made that I can remember.”

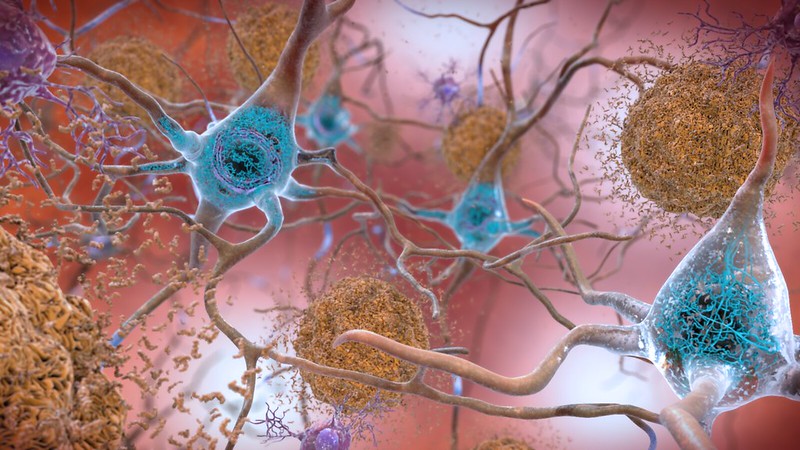

Part of the reason that the advisory committee agreed that the drug was not effective is that the two clinical trial datasets that Biogen presented showed divergent outcomes. One showed a slight benefit in the reduction of plaques at a high dose and the other showed no benefit at all.

The divergent results caused Biogen to conduct a ‘futility analysis’ and to halt the trials at the halfway point because the initial results were showing that the drug was not meeting its objectives. After abandoning those trials and working closely with FDA to assemble data observed from subgroups of patients post-trial, it resubmitted a new drug application. Even if the post-trial data had been convincing enough to show a decline in plaque accumulation, it would still not be enough for Biogen to make an efficacy argument, according to authors of a peer-reviewed article that examined the clinical trial data, including committee member Dr. David Knopman. Instead, it should have resulted in a new phase 3 clinical trial to confirm positive results before seeking FDA approval.

Thus, it was a curveball for advisory committee members when the FDA ended up approving the drug on an accelerated timeline using the endpoint of decreased amyloid plaques suggesting the drug’s ability to reduce cognitive decline in patients. The accelerated FDA drug approval is used for certain serious diseases that have limited treatment options and can be granted using data that predict, not necessarily establish that there is clinical benefit. The change in endpoint was not something the advisory committee had a chance to weigh in on, and the FDA chose not to reconvene the committee when deciding to use this new criteria for efficacy and ultimately, approval. That’s one of the reasons why one resigning member, Dr. Joel Permutten said that FDA’s decision “made a mockery” of the advisory committee’s role. And Dr. Knopman told FDA in his resignation letter that, “Biomarker justification for approval in the absence of consistent clinical benefit after 18 months of treatment is indefensible.”

Now that it has been approved under accelerated approval, Biogen will be required to submit follow-up data to FDA to confirm that the drug is having a clinical benefit. But how quickly those studies will be completed is unclear. The case for efficacy should have been made before the drug’s approval, not after thousands of people have been treated in a non-clinical trial setting.

Scientific integrity is needed in the drug approval process

In this case, there are enough experts with questions about the clinical trial data and apprehension about whether the drug works enough to justify the side effects and costs to warrant more caution. The FDA could have required an additional phase 3 trial rather than approving the drug. At the very least, it could have reconvened its advisory committee to examine the data needed to support its approval decision.

Advisory committees serve as vital checks on what should be science-based agency decisions. External advisors expect that their recommendations will be taken up by agencies and inform those decisions—otherwise why spend their valuable time volunteering to comb through hundreds of pages of trial data? If expert advice is ignored when making drug approval decisions, what is the point of establishing these committees? And what does it say to the public that the FDA isn’t making its decision using expert advice? Can the public fully trust that FDA is making decisions based on the science and not on pressure it’s getting from pharmaceutical companies with massive financial stakes in gaining its approval?

We need to establish a culture where agency scientists and advisory committee members feel valued so their important work can continue to support the scientific integrity of federal agencies. Unfortunately, breaches in scientific integrity in the drug approval process have been a perennial issue for FDA. It is an issue that cuts across administrations.

For example, in 2008, FDA’s Director of the Center for Devices and Radiology and Health approved a surgically implanted vagus nerve stimulator for treatment of cases of severe depression, even though the clinical trials had not proven it to be effective against depression. In the case of emergency contraception (Plan B), both the G.W. Bush and Obama administrations delayed approval of over the counter sales for all ages, despite the science supporting its safety and efficacy.

In our 2018 survey of federal scientists, we received many open-ended responses from FDA scientists expressing concerns about the integrity of the agency’s drug approval processes.

- Several scientists wrote about increasingly lenient documentation of safety and effectiveness, including one who wrote, “I do not believe there is adequate scientific evidence demonstrating safety and efficacy for approval of treatments for many orphan diseases. When FDA attempts to require such evidence, it is accused of ‘holding up approval of desperately need treatments.’ Also, for such submissions, the review clock has been shortened (deliberately I think) such that adequate review of available evidence can become problematic.”

- We also heard about FDA political appointees and supervisors making decisions that were in opposition to staff scientists’ recommendations. One respondent wrote, “There have been one or two occasions where the Office Director has approved a product that was rejected by the members of the review team. At the Office Director level, that individual has few details on the safety and efficacy of the product and may or may not be an expert in that particular scientific discipline.”

- This theme was echoed by another scientist who wrote, “I have not observed such impacts coming from political appointees, however our center leadership has pressured decision-making that is overly lax in the requirements to demonstrate safety and effectiveness. Leadership has also been unsupportive of regulatory action that would be seen as a negative enforcement of the food drug and cosmetic act (e.g. violations of labeling or study requirements).”

We should be able to rely on the FDA and all government agencies to use evidence to inform its decisions. That means fostering a strong culture of scientific integrity that prioritizes health and safety. One of the greatest features of federal advisory committees is that their meetings are transparent and inclusive of public comment. FDA decisions, on the other hand, do not offer that same level of openness. For cases like this, agencies should publicly document decisions not to bring charges to or to overrule recommendations of its scientific advisory committees and provide detailed explanations to support those decisions.

My heart goes out to those who have or whose loved ones have Alzheimer’s Disease. It is a devastating disease that robs people of their ability to function and interact with those they love. And yet, I am deeply concerned that the FDA’s decision will mean that patients will take an expensive medicine that doesn’t work and may cause unpleasant or harmful side effects. To truly help those with Alzheimer’s, we need treatments backed by evidence showing they work, rather than those FDA hopes will work.