Today, EPA Administrator Michael Regan proposed the Safer Communities by Chemical Accident Prevention rule. This policy includes long-awaited reforms to the Risk Management Program (RMP) rule, often called the Chemical Disaster Rule. It pertains to 12,000 facilities across the country that contain highly hazardous substances, and requires companies to develop plans for responding to a worst-case incident such as a major fire or explosion that might release toxic chemical pollution into the surrounding community. The consequences of such disasters are far from hypothetical—a long list of them have occurred across the country in recent decades. That’s why preventing chemical disasters must be prioritized over chemical industry demands.

At first glance, there’s reason to be optimistic about the rule’s potential. We are encouraged to see pieces that have been brought back from the Obama administration rule such as requiring assessments of safer technology alternatives, along with newer provisions requiring facilities to analyze natural disaster hazards in their plans, enhancing worker involvement in plan development, and requiring analysis of consequences to local communities for siting new facilities.

We’re still analyzing the proposal to determine whether EPA went far enough to ensure safer communities. I’ll be asking some key questions, such as: To what extent does the new rule center disaster prevention? Which facilities and chemical hazards will be subject to new provisions? How does the rule propose to implement the transitions to safer technology? How will analyses of community consequences be conducted and will cumulative impacts be considered? When will companies be expected to comply with the rule? And, exactly what information will be made available to the public?

The rule’s substance will show how serious the EPA is about its stated priorities of environmental justice, climate change, and worker and community safety. And, from what I’ve seen so far, it looks like the agency has more work to do in the coming months to ensure that this rule is as strong as needed to protect our communities from preventable chemical disasters.

Why this rule now?

The EPA estimates that approximately 150 serious accidents occur at regulated industrial facilities every year, resulting in deaths, serious injuries, evacuations, and other related physical and mental health harms. The Coalition to Prevent Chemical Disasters, of which UCS is a member, maintains a running count of chemical releases, fires and explosions that endanger and harm workers and communities in the US: since April 2020 there have been more than 600. In just ten years, there have been over 1,500 reported chemical releases or explosions at facilities regulated under the RMP rule, causing 17,000 reported injuries and 59 reported deaths. About 177 million Americans live in the worst-case scenario zones for chemical disasters and at least one in three schoolchildren attends a school within the vulnerability zone of a hazardous facility. Black, Latinx, Indigenous, and low-income communities are more likely to live at the fenceline of RMP facilities. Not only do they already bear the greatest burden of living next to the worst-polluting facilities, they simultaneously face the looming threat of calamity.

Nine years ago, President Obama issued an executive order asking federal agencies to modernize chemical safety rules in response to the West Texas disaster that killed 15 people, injured 200 more, and impacted thousands in the community. The Union of Concerned Scientists, along with more than 60,000 stakeholders and interested parties over the course of three years, provided numerous comments to carefully inform and help finalize the EPA’s RMP rule which required chemical facilities to follow common-sense best practices to enhance emergency preparedness and make communities safer. The modest progress made at that time was delayed and then stripped by a rule issued under the Trump administration in 2018. Last summer, EPA hosted a listening session on the rule which garnered hours of compelling testimony and more than 27,000 public comments. Members of the Coalition to Prevent Chemical Disasters, including UCS and our community, labor, environmental, public health and national security partners, met with the White House Office of Management and Budget to express the urgency and importance of a strengthened RMP rule.

During every one of the comment periods, listening sessions, and hearings, communities, workers, first responders and others told EPA about the urgency of prevention-focused provisions. The agency has heard what’s at stake and how to fix it. The details of this proposal will show us how well they’ve been listening.

The Chemical Disaster Rule is one of the best defenses we have against catastrophic disasters, and the final rule must prioritize prevention and deliver information and accountability tools that are accessible to and helpful for first responders and neighboring communities. By the time this rule is finalized next year, it will have been ten years in the making. It’s an unacceptable amount of time spent waiting for safeguards that have been needed by so many for far too long.

What a final rule must deliver

The Chemical Disaster Rule we have been advocating for would require the assessment and use of safer technologies, more accessible and quality information for communities near facilities including timely fenceline monitoring and reporting, improved emergency response coordination, and the consideration of climate-associated risks in the development of plans. Here are some of the specifics of what we believe should be in the EPA’s final rule.

1. Environmental justice

Environmental racism has led to the disturbing reality that people of color and the poor are more likely to live near chemical facilities. And, RMP sites and other hazardous facilities are woefully unprepared to deal with the effects of climate change. In a 2020 report, UCS found that 2.5 million more people of color would be disproportionately affected by extreme flooding of hazardous facilities along the East and Gulf Coasts as compared to white communities.

EPA’s rule should include eligibility criteria to expand to climate and natural disasters, fenceline monitoring with public access to sampling data and timely multilingual community alerts, and the prioritization of enforcement resources to address heightened risks due to natural disasters and climate change.

Along with requirements for switching to safer alternatives to eliminate hazards and fenceline monitoring to accurately hold facilities responsible, communities need access to realtime and accurate information about what materials are housed in these facilities and how they can best protect themselves and their loved ones in case of a disaster. Information justice is environmental justice. EPA needs to commit to making information about RMP facilities readily available and accessible to the public.

2. Worker and community health and safety

Workers and fenceline communities are on the frontline when chemical disasters occur. That’s why they need to be more involved in the development and continued accountability of facility Risk Management Plans.

RMP facilities must be required to report data to EPA that is accessible to workers, their representatives, and fenceline communities to prioritize public health and safety when preparing for and responding to chemical incidents, including natural disaster-related incidents. The new reforms should also require increased participation of workers and their representatives and in RMP plan development, and training in incident prevention, response, and investigation, including making workers aware of anti-retaliation protections and anonymous safety hazard reporting procedures. EPA should also ensure that these reports are made public and that there is a mechanism in place to require corrective action to prevent incidents.

Additionally, as facilities move to incorporate climate and natural disaster risks into their plans, they should ensure that workers at RMP facilities are trained and provided resources in their native languages on impacts to hazardous chemical processes, onsite emergency responses, and worker health and safety.

3. Explicit consideration of climate risks

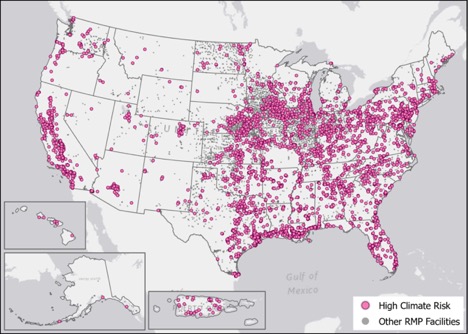

In a 2021 report co-authored by UCS, Center for Progressive Reform, and Earthjustice, we found that one-third—4,000 out of roughly 12,000—RMP facilities throughout the US are located in areas known to be at risk of inland flooding, coastal flooding, storm surge, and wildfires.

Despite the known risks, facility RMP plans are not required to consider these types of scenarios which has meant devastating consequences for facilities impacted by hurricanes and other natural disasters in recent years. In 2017, the Arkema facility outside Houston, Texas followed its hurricane preparedness plan when Hurricane Harvey struck, but the facility was not prepared for the unprecedented amount of flooding that overtook its power systems. When systems failed, organic peroxides at the facility became unstable. The resulting fires led to at least 21 people needing medical attention and 200 people forced to evacuate. More recently, the BioLab chlorine production facility in Westlake, Louisiana was damaged during Hurricane Laura in 2020, threatening its neighboring community with the release of toxic chlorine gas .

The evidence is clear: without strong safeguards in place, chemical companies will continue to do the bare minimum and people will continue to suffer.

Over the coming weeks, UCS will be analyzing EPA’s proposal to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the rule and how it can be improved before it is finalized next year. EPA needs to hear from you too! Stay tuned for more information from us on how to submit a public comment during this 60-day comment period and what to expect from the virtual hearings scheduled in late September. Together, we can make sure that our voices advocating for safer communities are heard by EPA.