China has a new leader. By all accounts, and according to most Chinese friends, colleagues and acquaintances I have asked— and I have asked many— Xi Jinping is the most impressive political figure to appear in China since Deng Xiaoping. This assessment seems to be based on the perception that after a single year in office, Chairman Xi has consolidated his control over the Party, the Army and the State bureaucracy.

Opinions differ on what Chairman Xi will do, both at home and abroad, with his exceptional political authority. But the appearance of a single individual who is willing to take personal responsibility for the national condition, instead of deferring to the collective leadership of his colleagues in the Standing Committee of the Politburo—China’s most powerful political institution— is a noticeable and important change in the status of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

One thing Chairman Xi’s ascendance has not changed is how the CCP tries to carry out its policies.

Two Types of Chinese Communist Propaganda

While the inner workings of the Chinese Communist Party hierarchy are a mystery to everyone who is not a part of it, the CCP still relies heavily on what it calls “propaganda” to govern the rest of the country. The English definition of the word implies deceit, and when reporting on domestic accomplishments or international conditions, less-than-honest manipulation of the words and images the Party presents to the Chinese public is not uncommon.

However, in a still-communist China—self-consciously more “red” under Chairman Xi than under his recent predecessors—there is a second type of Chinese propaganda that must be true to be effective. The CCP uses this form of political communication to articulate goals and expectations for the approximately 80 million Party cadres, including the senior-level officers of the Chinese military, who are responsible for making sure, to the best of their ability, that everybody around them understands what China’s political leaders want done. Communicating that intent is essential to the CCP’s ability to govern.

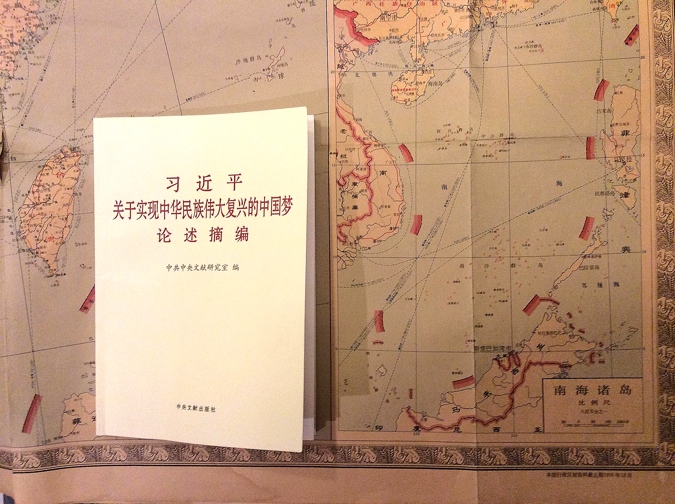

Every Chinese bookstore contains a well-stocked section of the pamphlets through which this second type of propaganda is routinely distributed. A lot of it is still presented in the same yellow covered, red-lettered publications that carried the selected sayings of Deng Xiaoping when I first arrived in China in 1984. The great thing about the continued use of this form of political communication is that it allows foreign observers to get a very clear picture of what Chairman Xi is telling his own cadres about where China is headed.

The Status Quo Holds

The guiding concept of Chairman Xi’s propaganda line is “Realizing the Chinese Dream.” This is a new turn of phrase that sounds like a cheap knockoff of “the American Dream.” But it isn’t. The full articulation, which serves as the title of the propaganda pamphlet meant to communicate the core of Xi’s policy agenda, reveals that the content of Xi’s “Chinese dream” is not new at all. On Realizing the Chinese Dream of the Great Renaissance of Chinese National Culture (pictured below) is a dressed up version of the long-term objectives articulated by Deng Xiaoping in the late 1970s. The overriding goal, to which all others are subordinated, is to achieve a “society with modest and broadly distributed prosperity” and in doing so create the economic conditions for a renaissance of Chinese culture. The former idea was a concept from the Confucian classics resurrected by Chinese intellectual Kang Youwei in the 1880s. China’s first President, Sun Yatsen, popularized the idea of a Chinese national renaissance during his successful effort to overthrow China’s last imperial dynasty and establish the Republic of China in 1911.

Other familiar Chinese revolutionary phrases, such as “the people are the creators of history” and “the masses are the real heroes” can be found in Chairman Xi’s pamphlet. But he also sets some rather explicit goals, such as doubling 2010 national GDP and per capita income levels by 2020. A longer term objective is to “build a prosperous, strong democratic civilization” and a “harmonious modernized socialist nation” by mid-century. The phrasing is slightly updated, but these are the exact same objectives set by Deng Xiaoping when he started the process of “reform and opening up” in the late 1970s.

Most importantly for U.S. observers is that Chairman Xi tells his CCP cadres that in order to make the Chinese dream come true, “China must have a peaceful international environment.” This was another pillar of Deng Xiaoping’s thinking. This does not mean China will, in Xi’s words, “give up our sovereign rights” or “sacrifice core national interests.” Deng made this clear to Margaret Thatcher in 1984, when he compelled the “Iron Lady” to surrender Great Britain’s perfectly legal claim to perpetual sovereignty over the island of Hong Kong, which was based on the Treaty of Nanjing. Chairman Xi is asserting sovereign claims in the South China Sea and in China’s island dispute with Japan, but these claims are not new, nor is Xi’s effort to make sure they are well-understood by those who dispute them. But the idea that China’s new leader is attempting to change a domestic or an international status quo that has served Chinese communist objectives since Deng Xiaoping ruled the country three decades ago is not borne out by the political directives he distributes to Party cadres.