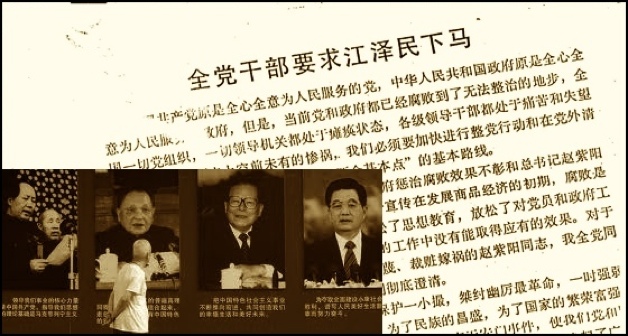

Twenty-three years ago an American undergraduate studying in China received a strange one-page Chinese-language memo tucked in a letter from his mom. It was an off-kilter photocopy of an incendiary political missive calling on all Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials to demand the resignation of CCP General Secretary Jiang Zemin. Jiang had been appointed to the top post a few months earlier in the wake of the Tiananmen Massacre.

The student brought the memo to me. He was a participant in the study abroad program I directed at Nanjing University. We decided it was best not to talk about it, so I slipped the memo into a plain manila envelope and forgot about it, until yesterday. I rediscovered it going through some old files.

It is still not clear how this memo made its way into the letter my student received.

The complaints in the memo, and the political drama it describes, could have been written yesterday. It begins with a grave statement on China’s national condition that would not be unfamiliar to the Chinese political illuminati microblogging on disgraced CCP politician Bo Xilai and the upcoming Chinese political transition.

“The Chinese Communist Party originally was a party that served the people with all its heart and will. The government of the People’s Republic of China originally was a government that served the people with all its heart and will. But today the party and the government are corrupt to the point of being beyond repair. Every party organ in the country, every leading institution is in a terrible state, leaders at every level are suffering and in despair.”

In the wake of Tiananmen, U.S. China hands offered multiple analyses of China’s changing politics, often accompanied by recommendations for U.S. China policy. Orville Schell called on a shamefully “timid” Bush administration to “put itself irrefutably on the side of democracy and this new generation of Chinese” who supposedly “had turned toward the U.S. for political inspiration and who will soon become China’s new political leaders.” Like many other U.S. China watchers, Mr. Schell argued that “relations between our countries cannot, and should not, be normalized until China either makes amends for its barbarity or falls from power.” Michael Oksenberg predicted a global “sense of revulsion” towards the Chinese Communist Party would “cost China a lot of money in the coming years.” Richard Holbrooke suggested China was on the verge of a civil war.

Looking back, all of those predictions and recommendations obviously missed the mark. Direct foreign investment continued to flow into a booming Chinese economy, President Clinton led China into the World Trade Organization and the Chinese Communist Party never “made amends” for the slaughter. American observers may have got it wrong because they tend to define Chinese politics using points of reference that are quite different than those used by Chinese political actors. The incendiary missive slipped into my student’s mail is a case in point.

In the memo, Jiang Zemin is depicted as a capitalist in socialist clothing, and the leader of a small clique of ambitious conspirators who used the relatively minor mistakes of deposed General Secretary Zhao Ziyang to launch a rightist coup d’etat. In Chinese political history the “rightist” label is most frequently associated with those who advocate what U.S. observers might call “liberal” economic and political policies in favor of both free speech and free markets. Zhao, according to the authors of the memo, will ultimately be vindicated by history as a good socialist. In this context it is worth noting that the “democracy” demonstrators on the streets of Beijing in 1989 were seen carrying pictures of Mao and singing the communist Internationale. The “Goddess of Liberty” wasn’t the only symbol, or even the most significant one, circulating during the protests.

This is a distorted mirror image of how many U.S. observers saw the two men and the demonstrations of the late 1980s. Zhao was, and still is, described by U.S. observers as the reformer, as the “liberal” official challenging the old communist order. Jiang was initially seen as a figurehead for the more conservative elements in the CCP who were afraid of reform, and who responded to Chinese public aspirations for change by ordering the Chinese army to gun down its own citizens. Deng Xiaoping, the “senior leader” who both pushed forward economic reforms and repressed the demonstrations with brutal military force, is described in the memo as a befuddled old man “living in a maze” and “surrounded by a small clique of conspirators.”

Perry Link argues that Deng was not befuddled at all but rather the mastermind of a post-Tiananmen political order that rotated between two imagined political camps, one headed by Jiang Zemin and the other headed by Hu Jintao, the current General Secretary of the CCP and the President of China. Before his death in 1997, Deng supposedly chose Hu to succeed Jiang, who surrendered his position, reluctantly, in 2002. Xi Jinping, who is scheduled to take the reins of power from Hu later this fall, is, according to Perry Link, associated with the Jiang faction.

Link and many other U.S. observers describe the current debate over the future of the Chinese political system in the same terms used in the old U.S. commentary on Tiananmen. The current political struggle over the transition to the incoming group of Chinese political leaders is supposedly a contest between “reformers” who want greater democracy as well as open markets, and the “authoritarians” who don’t. But which of the imagined factions is associated with which idea?

The authors of the 1989 memo champion a supposedly “reformist” Zhao Ziyang while calling for a return to Maoist “class struggle” against Jiang and his capitalist clique. Does that mean Xi Jinping, allegedly associated with Jiang, is an “authoritarian” and that “Maoism” speaks for the voices of democratic reform? As we watch the images of Mao appearing in recent anti-Japanese demonstrations, and recall how Maoist demagoguery was used by Bo Xilai to attempt to revive his personal political fortunes, we may want to pause before coming to conclusions about which side various groups of demonstrators may represent in the imagined Chinese political continuum of “reformers” and “authoritarians.”

The snippet of Chinese political history I rediscovered, and the off-base U.S. descriptions of China’s political future circulated when it was written, lead me to wonder if there is a definable Chinese political continuum. The country has also changed, dramatically, in the past quarter century. China’s economy and society are more independent, fragmented and complex than they were in 1989. Multiple coalitions of political sentiment and economic interest that have little to do with either reform or authoritarianism are likely to run through the 80 million individual members of the governing Chinese Communist Party.

The discos-to-democracy hypotheses of the 1980’s and the internet-to-democracy hypotheses of today are equally questionable. Just as the fall of the Soviet Union did not lead to the collapse of the Chinese Communist Party, the so-called “Arab Spring” does not necessary imply China is due for a “spring” of its own. Chinese youth, who Schell saw as inevitable agents of U.S.-inspired democratic change, seem to hold political opinions every bit as diverse as their parents and grandparents. While the recent nationalist demonstrations appear orchestrated, my own experience living and working in China over the last twenty-three years suggests the sentiments being manipulated are sincerely held. Youth does not guarantee a progressive political outlook in China, or any other part of the world, including the United States.

U.S. interest in China’s political future is understandable, but our benchmarks for assessing the pace and direction of political change in China may need an overhaul.