China’s top diplomat repeatedly told US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan his government does not believe the United States and China are engaged in a struggle for global supremacy. It was one of the most important issues—second only to Taiwan—that Foreign Minister Wang Yi raised in August during the latest in a series of secretive backchannel talks with Sullivan that began last year.

A US official familiar with the talks, held quietly in Vienna, Malta and Thailand, told a veteran US-China correspondent that the US competitive framing of the relationship, “was a really hard jump for the Chinese.” Sullivan did his best to convince Wang to accept what the reporter, echoing the US government, described as “the new reality.” Wang told Sullivan it is impossible to cooperate with a foreign government that believes it must prevail in what President Biden called a struggle with China to “win the 21st century.”

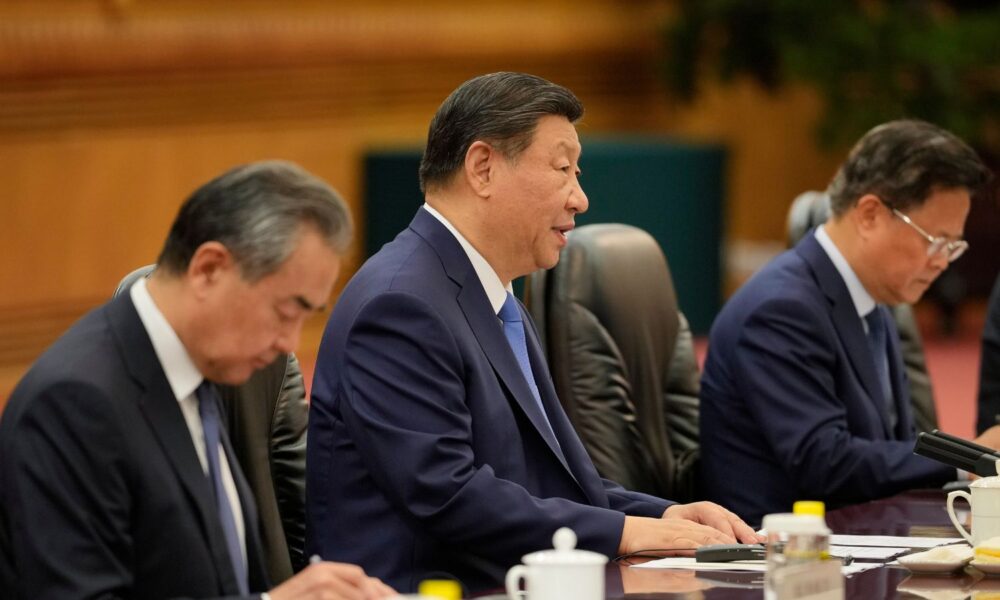

This week in Beijing, when he met with Sullivan a fourth time, Wang once again expressed the hope his government can work with US officials to create a future where both nations win.

Senior US diplomats used to express that same hope. But it was always conditioned on the expectation China would change, that its political and economic systems would become more like those in the United States, Japan, and the European Union. Xi Jinping, who was a dark horse candidate for General Secretary and the first in the history of the People’s Republic to be elected by his peers, finally convinced US elites the change they expected was unlikely to come. Xi won the job by promising he would clean up corruption and strengthen the Party’s commitment to communist principles.

Previous Chinese leaders were equally determined to preserve the political authority of the Chinese Communist Party by any means necessary, including using lethal military force to brutally repress nationwide public protests in June of 1989. So, it is difficult to know why it took another three decades, and the ascendancy of a third generation of Chinese communist leaders, for US elites to let go of the idea they could “reform” Chinese politics through economic engagement. Once they did let go, it was the United States, not China, that chose to subordinate cooperation to competition in US-China relations.

Xi Jinping drove that point home when he met with Sullivan in Beijing last month. He told the US national security advisor, “First of all, we must answer the general question of whether China and the United States are rivals or partners,” making it clear he believed, like his foreign minister, that it is impossible to be both at the same time. The Chinese leader said his government’s intention to pursue “peaceful development” was “above board,” suggesting Xi is uncertain about US intentions. He also implicitly criticized the US emphasis on competition by telling Sullivan the two governments should “find a correct way” to get along. Last summer, Xi told US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken, “Great power competition is not in keeping with the trend of the times, and is even less able to resolve America’s problems or the challenges facing the world.”

After US political and economic elites lost faith in the theory of “globalization” and gave up trying to transform Chinese politics through economic engagement, an economically successful and technologically advanced communist China seemed more threatening to US decision-makers who once championed cooperation with China. US international relations theorists, led by Harvard’s Graham Allison, legitimized those fears by revitalizing and popularizing the ancient theory that so-called “great powers” are destined to compete for supremacy. That theory rapidly replaced “globalization” as the intellectual lodestar for US foreign policy.

Jake Sullivan and the Biden administration are following Graham’s advice. The 84-year-old American political scientist wrote his book, Destined for War, in 2018 with the intent of helping US decision-makers avoid letting an assumed-to-be inevitable struggle for supremacy between the United States and China ignite a war. During the recent backchannel discussions, Sullivan repeatedly told Wang that to keep the peace, China and the United States must adapt to this inevitability. But Wang and Xi told Sullivan and Blinken they see the bilateral relationship differently. They don’t believe Graham’s rearticulation of an ancient theory of international relations is a viable guide for how the governments of the United States and China should behave today.

In this sense, China’s communist leaders are more flexible, optimistic and forward-looking than their US counterparts.

[NOTE: This post was updated to remove an error related to when Xi Jinping became General Secretary.]