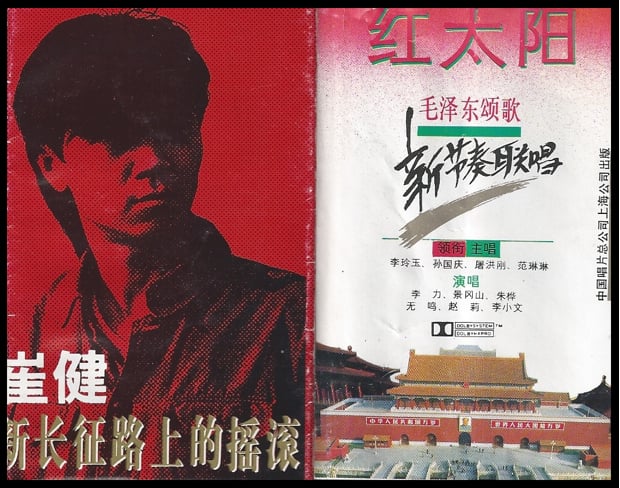

Cassette tape inserts from the early 1990s. On the left, Cui Jian’s “Rock & Roll on the New Long March.” On the right, “Red Sun: Mao Zedong Leadership Songs.” Cui’s rock rendition of the Communist Internationale was sung by student protesters during the 1989 demonstrations and banned afterwards. Red Sun is one of many pop renditions of CCP revolutionary classics that appeared during a wave of Cultural Revolution era nostalgia that swept over China in the early 1990s.

On 19 August the New York Times reported the current Chinese leadership is cracking down on “Western ideas.” If I had a dollar for every time I read a similar statement in a U.S. newspaper over the past 30 years I could buy myself a new smartphone.

The apparent trigger for the headline was the journalist’s recent exposure to Document #9: a memo from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Central Committee General Office, described by the journalist as “the administrative engine room of the central leadership.” Issued in April, the memo contains a tired litany of familiar phrases warning CCP cadres to keep up their ideological guard.

Some Chinese and foreign observers appear concerned the popular appeal of politicians like Bo Xilai—now on trial for corruption—and Xi Jinping’s apparent adoption of Bo’s “red” propaganda, could be signs China is headed for another Cultural Revolution. They may be reading too much into relatively familiar patterns in China’s post-Mao politics.

In the summer of 1984, when I first traveled to China as a graduate student, Deng Xiaoping’s “spiritual pollution” campaign was in its final stages. In the fall of 1989, when I took my first job in China, Jiang Zemin’s campaign against “bourgeoise liberalization” was just getting started. Much like the contents of the current memo, these two prior campaigns against “Western” ideas—excluding Marxism, of course—included warnings that foreign forces were trying to change China’s domestic politics through “peaceful evolution.” Former CCP General Secretary Hu Jintao’s multi-year campaign to promote a “harmonious society” was a less strident way of emphasizing the same thing: the importance of one-party rule and the dangers of the liberal notions of divided government, an adversarial judicial process and an independent press.

While it is possible the political rectification effort promoted in Xi Jinping’s Document #9 signals a significant shift to the left in China’s domestic politics, it resembles similar efforts launched by all of his predecessors in the post-Mao era. Each one was accompanied by arrests of dissidents, measures to restrict the media and well organized programs to rectify ideological trends the Party found threatening. The “spiritual pollution” campaign was a response to the “Democracy Wall” movement. The assault on “bourgeoise liberalization” followed several years of massive nationwide protests the CCP finally chose to repress with lethal military force. Hu Jintao presided over the conviction and sentencing of Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo for organizing support for a charter calling for democratic reform.

None of these campaigns, however, led to a return to the leftist politics of the Maoist era. Xi Jinping’s Document #9 is not likely to either.