In 2007 and 2010 China conducted anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons tests, both on January 11. Rumors circulating for the past few months suggest that some within the U.S. defense and intelligence community believe China is preparing to conduct another ASAT test.

The first media report on these rumors appeared in October. China’s Ministry of Defense challenged the information in that report, but in November contacts in China told us an announcement about an upcoming ASAT test was circulated within the Chinese government. We were unable to find a public statement confirming plans for a test in the Chinese media or on publicly accessible Chinese government websites. Then, just before Christmas, a high-ranking U.S. defense official told us that the Obama administration was very concerned about an imminent Chinese ASAT test.

Given these high-level administration concerns, and past Chinese practice, there seems to be a strong possibility China will conduct an ASAT test within the next few weeks. What kind of test and what the target might be is unclear.

The Obama administration has three choices: it can make a quiet diplomatic effort to persuade China to cancel or at least postpone the test, it can publicly call on China not to test, or it can remain silent until China conducts the test and then complain about it afterwards. The Bush administration took the latter approach and the space environment is much worse off for it. Despite having seen the ASAT system tested at least twice before the Jan. 11 2007 destruction of the Fengyun 1C, the Bush administration did not communicate its concerns to China, and we will never know if this might have influenced China’s decision.

The Obama administration should try to dissuade China from conducting the test. China may decide to test anyway, but it might see value in canceling or postponing the test to discuss these issues with the U.S. The Chinese Foreign Ministry routinely expresses support for diplomatic efforts to create an international space security framework. This approach is also in line with U.S. Defense Department policy. Its Oct. 2012 Directive on Space Policy, which lays out the range of approaches the DOD will take to mitigate the threat posed by the development of systems that can interfere with satellites, says it will “support the development of international norms of responsible behavior” in space. Acting to prevent irresponsible behavior before it happens is a clearly preferable approach to supporting international norms than waiting to act until after they have been violated.

High-level intervention in both countries is needed to stop the test and start discussions. Remarkably, there are no regular channels of communication on space issues between China and the United States. Congressional opposition to scientific and commercial cooperation with China in space shut down potential talks on human space flight that could have led to a bilateral dialog on space security.

If China fails to respond to bilateral efforts, the administration should issue a strong public statement prior to the test to increase international pressure on China to cancel it.

What Kind of Test?

The Chinese ASAT test in 2007 targeted an aging Chinese weather satellite in a low earth orbit approximately 850 km above the earth. The ASAT interceptor struck and obliterated the one-ton satellite, creating a large field of space debris that will present a danger to spacecraft orbiting near that altitude for decades.

The 2010 test was conducted as a missile defense test, destroying an object that was not in orbit, so it did not create any long-lasting space debris. The intercept occurred at a much lower altitude than the 2007 test, and targeted a mock warhead launched by a ballistic missile rather than a satellite in orbit. But China reportedly used the same launcher and the same interceptor in both the 2007 and 2010 tests. Chinese defense and aerospace analysts contend that there is no technical distinction between ASAT interceptors and missile defense interceptors that work above the atmosphere, and have argued since the 1980s that they are essentially the same technology (and U.S. analysts agree). That the second test used the same technology in a non-debris creating way may indicate that China now understands the problems associated with tests that destroy satellites.

It is not clear what kind of test may be planned, if indeed one is in the works. There are different types of technologies that can be used as ASAT weapons and a satellite may not be destroyed at all. The planned test could be of the same technology as the 2007 and 2010 tests but in a missile defense or flyby mode, or a test of technology that doesn’t destroy a satellite.

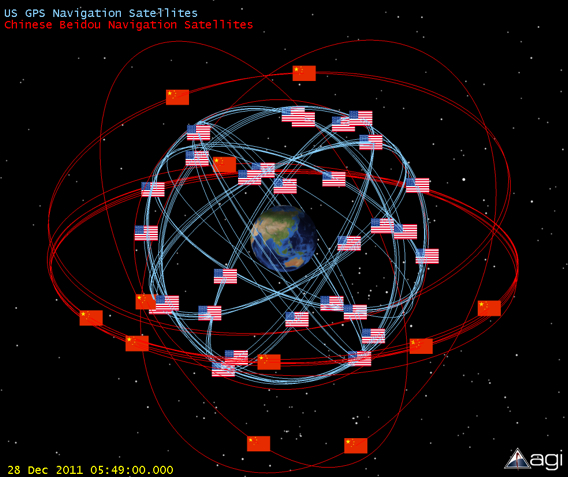

The first U.S. media report suggested that the next Chinese ASAT test, if it occurs, could be at a much higher orbit than the 2007 test. U.S. government sources informed us that some U.S. defense and intelligence analysts think China may attempt to strike a target at an altitude close to the medium earth orbits (MEO) used by U.S., Russian, and some Chinese navigational satellites, which orbit at about 20,000 km above the earth.

Such a test could be interpreted as a signal China wants to hold U.S. GPS navigational satellites at risk, much as the 2007 test was interpreted as a signal China intends to attack U.S. satellites in low earth orbit. But there are good reasons for China not to destroy a satellite at this orbit, including that China plans to use this part of space. Creating debris, as it now understands, would threaten its own satellites. Over the next several years China plans to place more than twenty new navigational satellites in MEO. Together with the satellites already in orbit, these new launches will complete a Chinese satellite navigational system with capability similar to the U.S. GPS constellation, providing Chinese civil, commercial, and military users with valuable location and timing services.

Moreover, as we showed in a previous post, significantly reducing the capability of the U.S. GPS system would take a large-scale and well-coordinated attack, so much so that targeting these satellites may not be an effective strategy.

Ma Xingrui, the General Manager of the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC), recently compared the strategic significance of China’s new satellite navigation system to China’s nuclear arsenal. Given the large size of the investment, and the economic and military importance of this system to China, it is questionable whether China would ever actually use the ASAT interceptor it is testing to launch a large-scale destructive attack in MEO, or any other area of space where its satellites operate. China’s emerging space capabilities may be fewer and less capable than those deployed by the United States, but they are just as valuable to Chinese military planners and the Chinese leadership. Over the past several decades China has invested considerable financial, technical and human resources in the development of a comprehensive set of civil and military space programs.

China’s space program is still in the formative stages of its development. Both the United States and the former Soviet Union conducted equally high profile ASAT testing during comparable stages in the development of their space programs, and both eventually decided to stop destructive ASAT testing. Hopefully, China will eventually come to a similar conclusion. Beginning a meaningful bilateral dialog on space security between the United States and China could hasten the day.