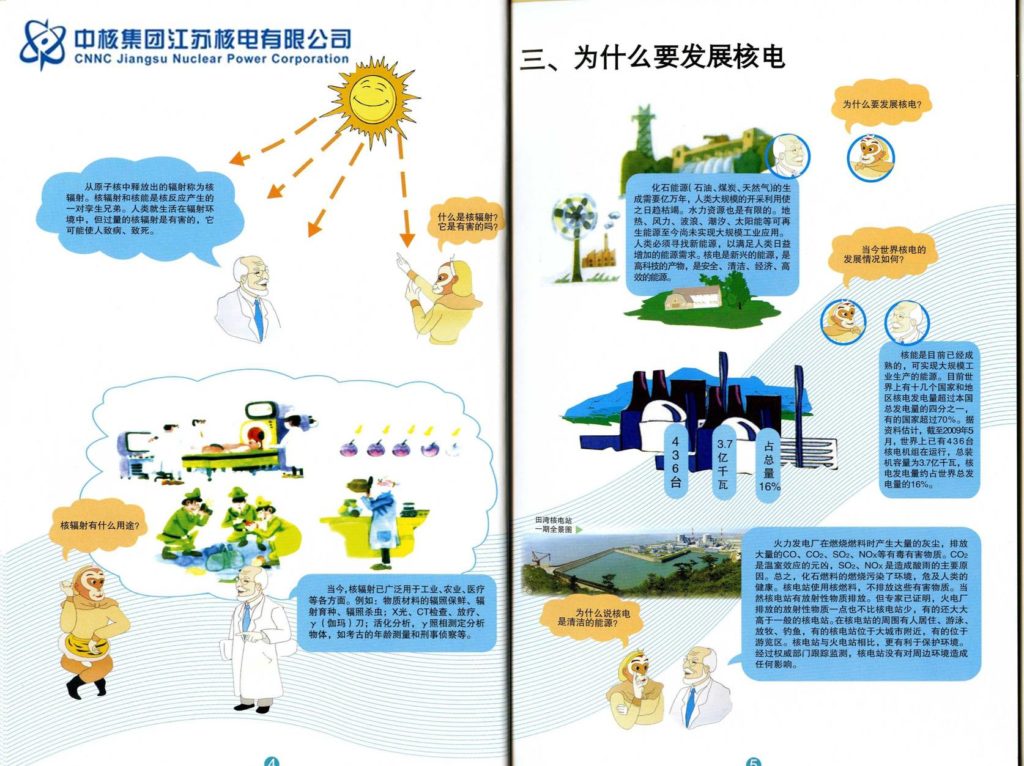

A page from an educational pamphlet produced by the China National Nuclear Corporation that answers the question “Why Develop Nuclear Energy.”

On July 13 the New York Times reported that local Chinese government authorities canceled plans to construct a nuclear fuel fabrication facility in the city of Jiangmen in Guangdong after several days of public protest against the plant.

A more detailed report in China’s Nanfang Ribao published a day earlier gives a more complete picture of the plans for the plant, the public’s reaction and the Chinese government’s response. The paper’s description of the prior consultations between the owners of the facility, the local government, national regulators, local residents and the broader Chinese public provides a useful window into the likely future of nuclear energy in China.

History of the Decision

The China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) signed a pair of agreements specifying capital allocations and land use rights for the fuel fabrication facility with the Jiangmen government at the end of March. CNNC hopes to supply not only China but other nuclear power plants in the region with fuel manufactured in what it calls a “state of the art” facility using recent Chinese breakthroughs in developing its own uranium enrichment technology. One of the reasons CNNC chose the site in China’s southeastern province of Guangdong, after an extensive year-long study examining 40 other possible locations, was the locality’s access to potential markets in southeast Asia. The Jiangmen government posted a public notice of the two agreements on its website immediately after they were signed. The posts were reported in the local media. There were few complaints.

These kinds of agreements were what the senior Chinese leadership envisioned after it moved regulatory authority for nuclear energy out of the hands of the now defunct Commission on Science and Technology for Industry and National Defense (COSTIND) into the Ministry of Energy as part of a series of comprehensive government reforms in 2008. CNNC saw the move as a prelude to a dramatic expansion of Chinese nuclear power now that the fully commercialized industry was free to negotiate directly with local authorities hungry for new sources of electric power.

The catastrophic accident at Japan’s Fukushima Daichi facility in March 2011 raised concerns among the Chinese public, and the Chinese leadership, about CNNC’s push for a rapid expansion of nuclear energy. The nuclear corporation’s ability to negotiate agreements was restricted by the central government, which also put in place additional regulations requiring a report on the “social stability” impacts of all large scale capital construction projects. It was the July 4 release of the “social stability” impact assessment for the CNNC fuel fabrication facility, and its publication on the Jiangmen government website, that triggered the protests that led to the story in the New York Times.

Response to the Protests

According to Nanfang Ribao, the Jiangmen government harbored doubts about the fuel fabrication facility from the very beginning. A prolonged CNNC lobbying campaign persuaded it to change its mind. CNNC hosted a delegation of Jiangmen officials at its fuel facility in Yibin, Sichuan. The officials were impressed with the operation. They noticed that the local population seemed undisturbed by the plant and that property values close to the plant were competitive with those in the rest of the city.

In the wake of the protests, the Jiangmen leadership took steps to educate its citizens about the safety risks and economic benefits of the CNNC fuel facility. In addition to sharing everything they learned from CNNC, the leaders invited nuclear energy experts from leading Chinese universities to give presentations to local groups concerned about the facility. The description of these efforts in the Nanfang Ribao story reminds me of presentations I received as a child from Baltimore Gas & Electric, which conducted a massive public relations campaign before building the Calvert Cliffs nuclear plant in my home state of Maryland.

Originally the Jiangmen government appears to have hoped that a 10-day extension of the period for public comment would allow them to persuade nervous protesters that CNNC could operate the plant safely. But the intensity of the protests convinced it to change its mind again. In response to public requests for clarification it issued a “red letterhead” statement on the municipal website announcing the project was cancelled.

In addition to providing a window into the local politics of a rapidly changing China, what the protests in Jiangmen also tell us is that public education about the risks and benefits of nuclear energy is likely to play an increasingly important role in the future of nuclear energy in China. It is important, going forward, that the Chinese public, and their local decision-makers, get a credible and comprehensive overview of those risks and benefits.

Final page from 1948 comic “Adventures Inside the Atom” produced by General Electric, courtesy of the Philosophy of Science Portal