Yesterday, I was fortunate to attend “A Celebration of Carl Sagan” at the Library of Congress. Hosted by Emmy award-winner and science-supporter Seth MacFarlane, the event welcomed The Seth MacFarlane Collection of Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan Archive to the library and included 13 esteemed speakers all of whom had personal connections to the man being honored. Each speaker had different stories to tell, but many concluded their talk with the same unanswered question.

The Seth MacFarlane Collection of Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan Archive is 798 boxes of Sagan’s documents including everything from drawings to to-do lists to a handwritten note from Sagan to President Carter.

Sagan’s legacy: The people and places he touched

Each speaker described in detail the ways Carl Sagan had affected their lives. For Bill Nye, it was a story of Sagan agreeing to meet with Nye, a former student of his, when Nye was first considering a TV show about science (what would later become Bill Nye The Science Guy) and wanted Sagan’s advice. For Neil deGrasse Tyson, it was a personal offer to stay with Sagan’s family when a young Tyson was visiting Cornell and the Ithaca snow threatened to cancel his bus ride home. For Jonathan Lunine, it was a series of letters he and Sagan had written back and forth when Lunine was a 14-year-old aspiring astronomer. The stories were a testament to the late great Carl Sagan, who in many ways was America’s first prolific and widely known science communicator.

By the time I enrolled as an undergrad at Cornell University, Professor Sagan had passed nearly six years prior, but his legacy there was still alive and well. The Sagan-inspired Planet Walk still marked much of downtown Ithaca and it ended with Pluto located at the Ithaca Sciencenter, which Sagan himself helped conceive. From Global Warming to Public Speaking to Environmental Law, my classes were filled with examples of the lasting work of Sagan both in his scientific field and for public outreach of science. “The best example of this is Cornell scientist Carl Sagan” I heard my professors say again and again.

“Carl Sagan believed in democracy. The more people who knew the science, he believed, the better off society would be.”

—Ann Druyan, author, producer, and Carl Sagan’s widow and long-time collaborator

The question on everyone’s mind

At yesterday’s event, the question speaker after speaker asked was the following: If Sagan were alive today, how would he react to our current state of affairs in science and society? “One of Sagan’s greatest achievements was his fight against pseudoscience,” noted David Morrison, the Carl Sagan Center Director at SETI, “but could he fight the pseudoscience of today?”

Other speakers wondered too: Would Sagan speak out about the misuse of science for political gain that is all too common now? Would he challenge the misinformation spread by politicians and journalists? Would he harshly condemn the recent harassment of climate scientists? What everyone wondered was this: Would Carl Sagan have done a better job at pushing back against these dangerous anti-science trends than we are today?

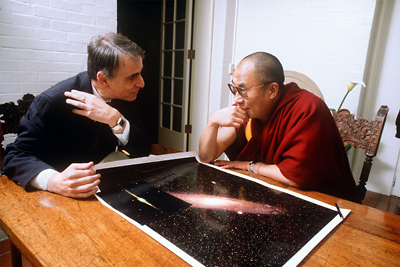

Carl Sagan felt it was his responsibility to communicate scientific information to diverse audiences from the general public to the Dalai Lama. Photo: Cornell University

These are tough questions and surely folks have pondered them before (Heck, there are even “What would Carl Sagan do?” shirts for sale.) But we now live in a different time than Sagan did. As Seth MacFarlane noted in his opening remarks, “There has always been politicization of science, but in recent years this politicization seems to be on steroids.” Indeed, this appears to be the case. UCS has found such problems in everything from chemical safety to gun control to endangered species to climate change.

“Let’s teach both science and hope”

Whether or not Sagan would be better at combating the challenges we face today in science literacy and (what should be) science-based policy, I believe he gave us the tools we need to take on these challenges ourselves. We can lament the loss of a great one, but let’s look to the future and carry his legacy forward through our own work. Sagan taught us that as scientists it is OK to step outside of our labs to bring science to the people; he showed us how to captivate the public with the wonders of science; and he demonstrated the need for science to inform broader societal challenges like international peace and STEM education.

For me, one of most important lessons from Carl Sagan is that achievement in science doesn’t stop with the scientific community. Scientists can and should apply their technical knowledge and training to the people and places that need it outside of their scientific fields and above all else, we should remain optimistic that these challenges are surmountable. As Christopher Chyba, a Princeton Professor and Sagan’s PhD student, concluded in his talk, “We need scientists operating at every point along the policy advising highway…Let’s teach both science and hope.”

Frontpage image courtesy of NASA.