Today we release our new report, Tricks of the Trade: How Companies Influence Climate Policy Through Business and Trade Associations. In the report we found that many companies choose not to be transparent about their affiliations with trade and business associations, even when the information is publicly available. In addition, we found that when companies did choose to disclose their trade group board seats, many claimed to disagree with their associations’ positions on climate change, raising questions about who trade groups are actually representing on climate policy.

Tricks of the trade: a history of trade groups blocking climate action

When I started to pore through company responses to the CDP climate reporting questionnaire, I didn’t know what I’d find. CDP, an international not-for-profit (formerly called the Carbon Disclosure Project), administers an annual climate reporting questionnaire to more than 5,000 companies worldwide at the request of 722 institutional investors representing $87 trillion in invested capital. The 2013 questionnaire was the first time CDP investor-backed not-for-profit organization asked companies about climate policy influence, including board membership in trade associations, lobbying, and donations to research organizations. What would companies voluntarily disclose about their political activities?

I knew from past UCS work that when it comes to influencing climate policy, many companies choose to outsource it; that is, many companies choose to support trade groups, think tanks, and front groups rather than engage in political activities in their own name. These trade associations and politically active organizations, in turn, can and often do, use corporate support to take more aggressive positions than companies would in their own name. And our further investigation of 14 major US-based trade and business associations found that many of these trade groups have opposed climate policy action and some still spread misinformation about climate science.

A lack of transparency: many companies choose not to report

In our new report, we used publicly available board member lists for the US Chamber of Commerce, the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), the American Petroleum Institute (API), and the Edison Electric Institute (EEI) and we analyzed if board member companies disclosed their board seat when asked about their board membership in groups that might “directly or indirectly influence climate policy.” For all four of these groups, less than half of board member companies disclosed this information.

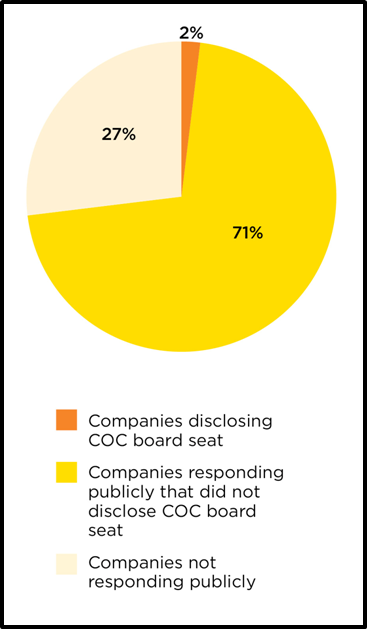

For the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, for example, only a single company on the Chamber’s 117-company board (UPS) disclosed their board seat, even though CDP requested information from 44 of their board-member companies. Thirty-two of those companies completed the questionnaire but didn’t include their Chamber board membership, as listed on the Chamber’s website (accessed December 3, 2013).

For NAM, API, and EEI, the rate of disclosure was similar. For the 112 NAM board members asked to complete the questionnaire, only 13 percent responded and acknowledged their board seat, even though another 35 percent of the board responded to the questionnaire.

Of the 32 U.S. Chamber board companies that publicly responded to the CDP questionnaire, only a single company, UPS, disclosed its board seat. The vast majority of the 44 U.S. Chamber board-member companies from which CDP requested information completed the questionnaire but failed to indicate their position on the board.

So this begs the question: Why aren’t companies reporting their board memberships in the CDP questionnaire? Are the employees completing the questions unaware of their companies’ board membership? Perhaps some fraction of companies weren’t aware of how their trade groups engage on climate policy. Though, CDP linked to the recent UCS report, Assessing Trade and Business Groups’ Positions on Climate Change in the questionnaire guidance document, in order to help companies know what these and other US-based trade groups’ positions on climate change are. In any case, the newly released data tell us that we still have a ways to go before companies are willing to be open about their political activities.

A lack of public support: many companies don’t agree with their trade groups’ climate position

The second main report finding was that when companies did choose to list these groups, many claimed to disagree with the trade group’s climate position. Of the 15 companies on NAM’s board who acknowledged their seat, nine of them reported that their climate positions were “inconsistent” or “mixed” with that of NAM. The Clorox Company, for example, explained “NAM maintains a neutral position on climate change. The Clorox Company, on the other hand, is on record as believing that rising GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions have a significant impact on climate change and the environment. Clorox therefore supports congressional action on comprehensive national climate change legislation…”

Other major U.S. trade associations with several inconsistent or mixed responses were EEI (eight companies), API (four companies), and the American Chemistry Council (ACC) (four companies). Air Products & Chemicals, Inc., for example, explained their differences with ACC and noted, “The ACC has challenged certain aspects of legislation and regulations related to climate change.”

Who do trade groups truly represent?

If companies claim they don’t agree with their trade groups’ climate position, who are these trade groups representing when they fight against policy action to address climate change? And importantly, who then is held accountable for trade groups’ policy stances? Without more information about corporate political activities, we can’t know who is actually supporting these groups. As a result, business and trade associations can wield enormous influence over public policy debates, blocking climate action and other policy initiatives that affect our health and safety, while the companies and others funding them can remain in the dark.

The influence of trade and business associations is a threat to our democracy and action must be taken to shed light on the secret donors of these and other dark money groups. One solution (that I’ll discuss more in depth in a future post) lies in the hands of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The agency has the power to enact a rule that would require publicly traded companies to disclose more about their direct and indirect political activities. Such a rule would bring much needed transparency to the role companies play in influencing climate change policy.

Join UCS in asking the SEC to enact the disclosure rule.