The following is an accurate description of Sandy, the superstorm that tore through the northeastern United States almost one year ago:

Sandy slammed into the New Jersey Coast Monday night, bringing very heavy rain and damaging winds to the region. The storm was a large one, with significant impacts in all areas. This was an historic storm with widespread wind damage and power outages, inland and coastal flooding, and massive beach erosion. The combination of the heavy rain and prolonged wind created long-lasting power outages and serious flooding. Sandy was an extremely dangerous storm. There was major property damage, injuries were unavoidable.

This is one of a series of posts highlighting issues related to the October 29, 2013 forum, Sandy, One Year Later: Looking to the Future.

But this passage, in fact, is not a description of Sandy’s impacts; it is the forecast for Sandy made by the National Weather Service’s Mount Holly, New Jersey, office. I changed the verbs to past tense to show the incredible accuracy of this forecast, which was issued at 2:41 pm on Sunday, October 28, 2012—some 30 hours before Sandy made landfall near Atlantic City.

The accuracy in the National Weather Service’s forecast of the never-before-seen mega-storm is a testament to our nation’s investments in environmental monitoring and modeling. Scientists have long recognized the importance of monitoring data, and forecast meteorologists know well that they would not have been able to create that accurate forecast, if they didn’t have the necessary tools.

NOAA’s Gulfstream-IV hurricane surveillance aircraft featured here and others fly near hurricanes and tropical storms to obtain precise measurements of storm strength and location to aid in weather forecasting. Photo: NOAA

The importance of measuring and monitoring

For any extreme weather event, meteorologists need many tools—powerful models coupled with observations from the ground, from the ocean, and from the air. But with Sandy, these tools became especially important as Sandy was unprecedented in terms of size, strength, and path. Meteorologists needed all the information they could get to help them predict Sandy’s behavior. They used observations of wind and pressure from stations up and down the east coast. They used wave height estimates from buoys in the Atlantic Ocean. They used satellite images to help determine Sandy’s strength and moisture levels. They used hurricane hunter aircraft data to get more detailed information on Sandy’s exact location and intensity. And they used radar to monitor the rain and severe weather associated with the storm. Importantly, meteorologists relied on powerful weather models to track Sandy starting more than a week in advance. This is the power of modern weather forecasting in helping us prepare for the worst that weather can bring.

Shortcomings in our community planning

But in other ways, we weren’t prepared for Sandy. Accurate and early forecasts helped emergency management and other short-term preparations to happen. But we couldn’t do much about the infrastructure that stood in Sandy’s path. These were the buildings, roads, and boardwalks built long before a tropical disturbance was ever spotted in satellite photos. The placement of this infrastructure is the result of our planning and zoning laws. Why had we allowed structures to be built in such vulnerable places? Didn’t we know that devastation like Sandy’s was possible?

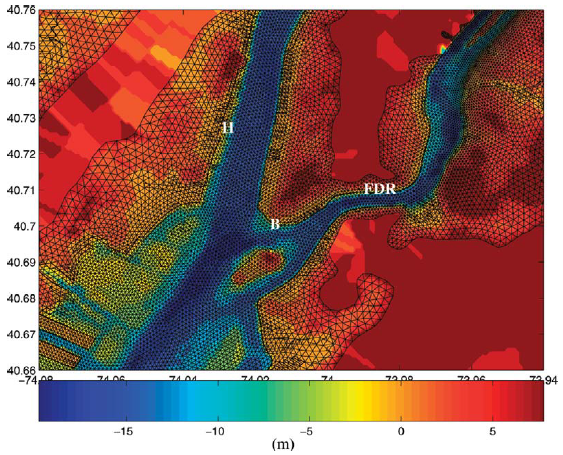

Scientists model storm surge and flooding impacts to predict the damage that storms like Sandy cause. These predictions can inform our community planning to mitigate future storm impacts. Photo: Colle et al., BAMS, 2008

Indeed, we did. Many years before Sandy became a household name, scientists predicted the impacts that a hurricane hitting New York City would have. More generally, scientists have created comprehensive maps and models of the impact that sea level rise will have on our coastal cities. These scientific predictions could have been—and still should be—used in our coastal planning. The scientific information we currently have on sea level rise, storm surge, and other coastal impacts can help us create guidelines on if and how to build infrastructure so that we can have more resilient communities. UCS’ upcoming Branscomb forum, Sandy, One Year Later: Looking to the Future, will explore how we can get there.

To truly be prepared for future storms and future sea level rise, we will need to maintain comprehensive environmental monitoring and modeling for weather forecasting and we will need to utilize science in planning our communities. As I’ve noted before, science can’t tell us what to do about risk, but it can help us make better decisions for managing it.