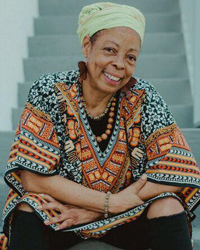

As sea levels rise, wealthier homeowners seek to reduce their risks of chronic inundation and dwindling property values by moving to higher ground, often to communities that have been traditionally poorer and Blacker or browner. As community advocate Paulette Richards describes in this guest blog post, the risk of “climate gentrification” rises right along with sea levels. Coastal residents who were sometimes forced into the higher elevation communities either by affordable housing costs or outright redlining are now at risk of being forced into areas with higher climate risks. Millions of people around the world are facing this challenge, as Colette Pichon Battle of the Gulf Coast Center for Law and Policy explains in her TED talk. In this blog post, Ms. Richards describes her own experience with the dual pressures of climate change and climate gentrification. She won’t go without a fight.

My story

I moved to Liberty City in 1977 to live with my mother when I was expecting my first child and about to be a single mother. After my son was born, I moved out on my own to Victory Homes – affordable public housing units in Liberty City – and then I had a daughter and a second son. Liberty City was different then – it was a close-knit community where everyone looked after each other. My neighbors, Mr. and Mrs. Kitt, helped watch my children. They looked after us. Mr. Kitt became a father figure to me and was the first person I called “dad”. My neighbors and I would care for each other; we had what we needed in our community. This glued me to Liberty City, and it gave me the chance to dream about my future.

When my sister was murdered, her three kids came to live with me. As a single parent, raising six children, I wanted to own a home; to realize the American dream of homeownership and support my kids. I worked seasonal jobs, baby-sitting, and catering. Once I had gathered a small nest egg, I searched for a house, but it was hard to find a place I could afford. Finally, in 2000 I found a home that I could afford, that passed the inspection and that I loved. When my lease ran out, my children and I moved to a motel and stayed there for 8 months until I could close on the house.

When I had the keys to our new home, we couldn’t wait to move. We got a ride from one of our neighbors, and when we arrived we quickly ran through the front door. We saw the expansive floor and all the space for us in the house… This was all mine. While the kids each claimed their rooms, I walked out into the backyard. As long as I can remember my nickname was Mango because I love mangos so much. I looked at the mango tree in the backyard and tears ran down my face. I saw myself with a bucket of water and my sharp knife, washing, slicing and eating up mangos. Something I have been doing every mango season for almost 20 years now. I have invested blood, sweat and tears in this home. I raised my kids and my grandchildren in this house, and I am now raising my 3-year-old great-granddaughter here. Over the years, I’ve have also sheltered community residents that were homeless or only had unsafe places to stay.

Climate gentrification

Because of climate change, I’ve seen the end of mango season move from July to September with the warming climate. I’ve also seen the growing interest from developers that are moving from building high-end condos in the flood prone coastal communities of Miami Beach to higher elevation communities like Liberty City (more than 10ft above sea level) where we are less vulnerable to sea level rise related flooding, but, because of limited resources, more vulnerable to predatory real estate developers. I saw this starting to happen in 2010. It felt like a different type of the gentrification than we, in Liberty City, had been dealing with. I knew it was driven by climate change and so I began talking to my community about what I called climate gentrification.

Fighting for the future

I’ve made it in this community and in this house though struggle. I’ve given back to my community by organizing to promote equitable affordable housing with LIFT, Low-Income Families Fighting Together. I led women leadership trainings to empower young women in my community (this turned into Women in Leadership Miami), started a girls’ mentorship program, and provided support for survivors of domestic violence. I also started a climate change arts program and an environmental summer program to take kids to the Everglades and to prepare them for the school year with school supplies and backpacks. I was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2013 and fought to stay afloat without health care. Hurricane Irma hit in 2017. The storm left major damage, more than half of the roof caved in. We lost my children’s clothes; furniture, my art collection, and my grandchildren were no longer able to live with me. It broke up my family – everyone going to different places for a while. Because I had fallen behind in my mortgage, the insurance company refused to accept my insurance claims to do repairs and so I had to scrap together what I could to do only the most necessary repairs.

Now I worry that one day somebody will come to my door and tell me my house has been sold. I receive text messages, phone calls, and 10-20 letters a day from people who want to buy my home but offer less than I owe. They are like piranhas, harassing me and my neighbors. 20 years ago, we might get a letter or two from attorneys interested in helping folks avoid foreclosure or wanting to refinance, but now everyone gets these letters, even when folks are not in foreclosure. The reason why the developers don’t offer homeowners what the homes are worth is because their intentions are to gut or demolish the homes. In our community we believe that this is not support for us but is being done to make room for the wealthy people that are coming here because it is less vulnerable to sea level rise. We have no protections from these developers. How many times do I have to tell them that this is my home and I’m not going to sell?

People who have been bought out are scattered all over the place, and public housing representatives are directing folks down south to Homestead. Housing is less expensive there, but the cost of commuting is too high and the elevation is too low. We refuse to go south to Homestead because of concerns over sea level rise, flooding, and the possible climate change vulnerability of the local nuclear power plant. We’re caught between steel and sea level rise. They are now offering public housing and section 8 assistance several counties to the north and folks have begun to move north.

In the last ten years, the community has gotten progressively worse. Now most of my neighbors are gone. Some rent if they can afford the high prices and some are homeless. Climate gentrification is making the housing crisis worse. The folks that do live here now don’t speak to each other, they just come and go. We need to act on climate and protect homeowners like me from being forced out. My dreams have faded, yet I hope that we can still bring back our community. I have invested my life in this community. I have earned the right to live out my days here and I will not go without a fight.