This week the Union of Concerned Scientists released a new report entitled Too Hot to Work: Assessing the Threats Climate Change Poses to Outdoor Workers.

Using data from 2019’s Killer Heat report, the new Too Hot to Work analysis examines the health and economic threats posed to the nation’s approximately 32 million outdoor workers in various occupations including construction, agriculture, and emergency response.

Disproportionately represented by people identifying as Black, African American, Hispanic, or Latino, outdoor workers are particularly at risk as climate change makes dangerously hot days more frequent and intense. If we don’t take aggressive action to mitigate global warming pollution, UCS found that outdoor workers’ exposure to days with a heat index above 100°F would increase three to fourfold with slow or no action to reduce global heat-trapping emissions. Let’s take a look at three Midwest states—Illinois, Michigan, and Minnesota—and the scope of the problem of extreme heat, the importance of outdoor workers to Midwestern economies, and what states and employers can and should be doing to protect them from extreme heat.

This is both an urban and rural problem

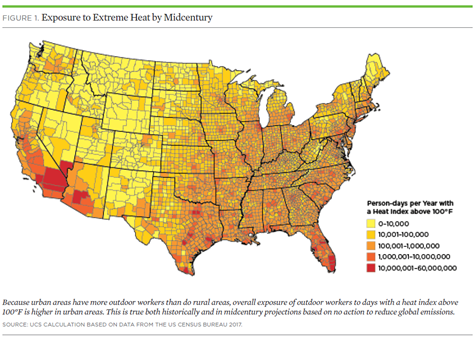

Because more populated urban areas have more outdoor workers (in terms of sheer numbers), the overall exposure of outdoor workers to extreme heat “person-days” (calculated by multiplying the number of days with a heat index above 100°F by the number of outdoor workers) is higher in urban areas. For example, UCS found that Cook County (Chicago) and the St. Louis Metro-East (East St. Louis) area in Illinois; Wayne, Macomb, and Oakland Counties in Michigan (Metro Detroit); and Hennepin County (Minneapolis) in Minnesota would all have more than 1.5 million person-days per year with a heat index above 100°F by midcentury based on no action to reduce global emissions. Depending on the county, that amounts to a four- to fourteen-fold increase in outdoor workers’ exposure from historical averages.

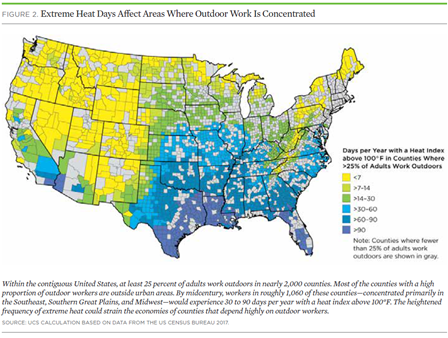

Looking at less populated areas, most of Illinois and southern Michigan counties would have 10,001-100,000 person-days a year as shown in Figure 1 above. In addition, UCS found that Illinois has numerous counties in the central and southern portions of the state where greater than 25 percent of adults work outdoors. Many of these counties are projected to have 30-60 days per year with a heat index above 100°F. And some counties in Southern Illinois would have 60-90 days—again, by midcentury, if no significant action is taken to reduce global emissions.

The role of outdoor workers in Midwest states

According to the Illinois Department of Employment Security, the agricultural sector contributes about $121 billion to the state’s total economic output. And the Illinois Migrant Council points out that Illinois farms employ close to 21,000 seasonal farmworkers, who often have very low incomes and suffer from disproportionate health disparities.

Agriculture is also a top industry in Michigan, along with recreation and tourism. And, according to the Michigan Bureau of Labor Market Information, construction-related employment is expected to grow by 6 percent or more in the state this decade. This makes sense as Michigan and many other Midwest states are in desperate need of rebuilding roads, addressing water infrastructure, and retrofitting aging homes and other buildings. Illinois, for its part, has over 180,000 workers in construction-related occupations (not all of which are outdoor roles, however).

The story is similar in Minnesota, with agricultural production and processing generating over $112 billion a year in economic impact and construction-related jobs expected to grow over 9 percent between 2018-2028.

As in other states across the country, many other types of workers spend much of their time outdoors in the Midwest, including those in emergency response, building and grounds maintenance, installation and repair, materials moving and transportation, and delivery services. Increased exposure to extreme heat means that, to stay safe, employers will need to allow employees to reduce their work time and increase their rest time. But those reduced work hours pose a risk to outdoor workers’ earnings. UCS found that, depending on the trajectory of future heat-trapping emissions, $39.3 to $55.4 billion in outdoor workers’ earnings would be at risk annually by midcentury in the U.S. Reduced earnings for outdoor workers could also mean less local tax revenue and greater demand on public services, as well as potential disruption of essential services the workers provide.

What can Midwest states do to protect outdoor workers?

Continue reducing emissions. Taking bold action to limit climate change and reduce the amount of extreme heat we’ll face by midcentury and beyond is critical to protecting outdoor workers. In addition to demanding climate action at the federal level and supporting international agreements to limit carbon pollution, we can take important steps to ensure Midwest states are leading the way and doing our part to reduce emissions. In Illinois and Minnesota, we need to enact commitments to achieve 100 percent clean energy, and in Michigan create a robust action plan for achieving the state’s goal to reach economy-wide carbon neutrality by 2050.

Enact worker protection standards. The new UCS analysis notes that, while federal agencies like the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have recommendations with respect to heat exposure, they are voluntary. At the state-level, only California and Washington have set permanent, enforceable heat-related protections for outdoor workers. Minnesota has a heat-standard for indoor workers; it, along with Illinois, Michigan, and other Midwest states should consider establishing heat protections for outdoor workers.

Create state task forces. The UCS analysis recommends that federal agencies such as OSHA and others work in coordination to establish a task force for making recommendations for detecting and preventing heat-related illnesses. States like Illinois, Michigan, and Minnesota can contribute to national efforts like these by forming their own task forces, drawing on expertise at state agencies and universities with knowledge of local conditions, and to bolster establishment of state-level regulations regarding outdoor workers and extreme heat.

Outdoor workers are essential and valuable members of our state and national workforce. Let’s make sure that an equitable response to climate change protects them.

Special thanks to Victoria Coleman, UCS Climate & Energy Program Associate, for research assistance in preparing this blog post.