On July 30, I will be testifying in support of the EPA’s power plant carbon standard at a hearing in Denver. As one of four locations where the EPA will be seeking public comment on the draft rule this week, Colorado is a mighty fine choice. The Rocky Mountain State is well positioned to exceed its proposed carbon emissions reduction target and serves as an excellent example of how a state can successfully transition toward a low-carbon, clean energy economy.

Colorado’s emission reduction target

This post is part of a series on the EPA Clean Power Plan.

On June 2, the EPA released a draft rule that would for the first time limit carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from existing power plant sources. It is an historic and critical step forward in reducing CO2 emissions in the electricity sector, which at 40 percent of the total, is the largest single source in the United States.

The draft EPA rule would reduce nationwide power sector emissions to 30 percent below 2005 levels by 2030, but that is simply a reflection of the aggregate of individual state targets. Emission rate reduction targets are established at the state level and are meant to account for specific conditions and opportunities in each state.

Colorado is required to reduce its carbon emissions rate to 35 percent below 2012 levels by 2030. The EPA arrived at that target by evaluating Colorado’s potential for technically and cost-effectively reducing emissions using four different types of solutions. Referred to as “building blocks,” these include: (1) heat rate (or boiler efficiency) improvements at existing coal-fired plants, (2) shifting generation from coal to natural gas, (3) generating electricity from low carbon resources (including renewable energy and preserving nuclear generation that may be at risk of retiring), and (4) increasing energy efficiency.

The EPA doesn’t require that states deploy all these options, but instead provides them with the flexibility to design and implement their own compliance plans.

Already on the right track

To some, a 35 percent reduction in the emissions rate may sound daunting. But the fact is that Colorado’s citizens, utilities, and policy makers have been making and implementing a host of smart, low-carbon decisions for a decade now that put the state in the driver’s seat for achieving the new standard.

Take renewable energy, for example. Way back in 2004, Colorado voters adopted a renewable electricity standard (RES) via a ballot initiative that at the time required utilities to supply 10 percent of their power from renewables by 2015. Developing wind and solar in Colorado has proved so successful, that since that time the state legislature has increased the target to 30 percent by 2020 for investor-owned utilities and 20 percent by 2020 for all others.

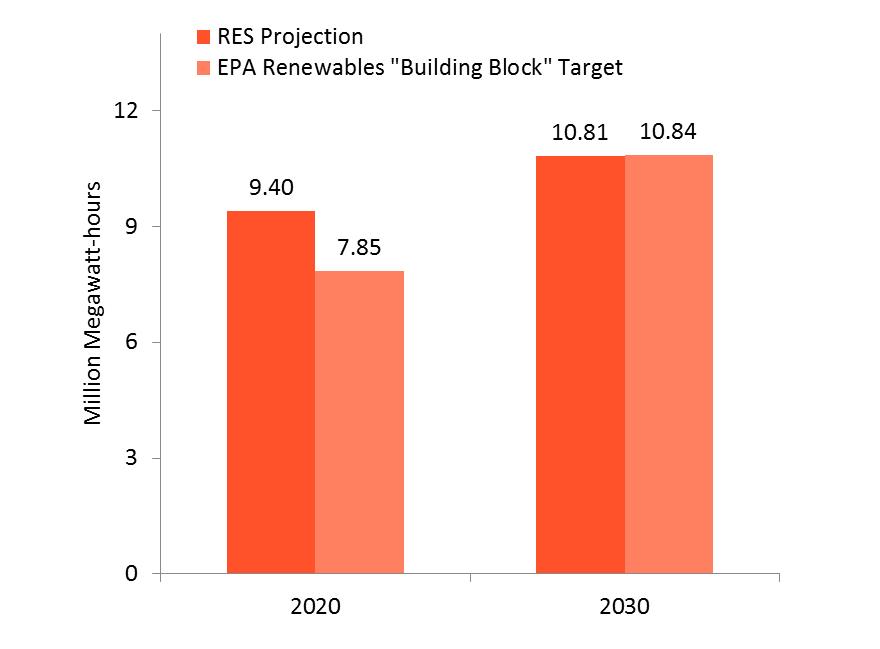

If Colorado did nothing more than achieve its current RES target by 2020 — and with 14.3 percent coming from renewables in 2013 they’re already nearly halfway there — that alone would virtually match the renewables building block established by the EPA through 2030 (see chart below). Of course, it’s highly unlikely that the state will stop deploying renewables after 2020, especially since wind and solar are becoming so cost-effective. In fact, Xcel Energy — Colorado’s largest utility — is projecting that about 22,000 solar rooftop systems (link requires subscription) will be installed in the state each year by 2020.

The story is very similar when it comes to energy efficiency. One of 26 states that has adopted an energy efficiency resource standard, Colorado is also already making solid investments in efficiency that will help the state comply with the EPA target. For example, ACEEE estimates that Colorado’s EERS will deliver annual electricity savings of 8 percent by 2020. That is more than double the 3.9 percent electricity savings embedded in the EPA’s efficiency building block in 2020. Under the EPA proposal, the efficiency target increases to just 11 percent by 2030. By simply extending its current policy beyond 2020, the savings in energy efficiency will afford Colorado great flexibility in cost-effectively achieving its required emissions rate reduction.

Retiring uneconomic coal

As in many other states, Colorado’s old, dirtiest, and least efficient coal generators are finding it difficult to remain economically viable when compared with modern, cleaner alternatives like renewable energy, energy efficiency, and natural gas. Since 2012, six coal generators totaling 708 megawatts (MW) of capacity have been retired in Colorado, and another two coal generators (363 MW) are scheduled to close by 2017.

These coal plant retirement decisions will go a long way in helping Colorado to comply with the carbon standard. In fact, the generation from these coal units is approximately 41 percent of the total amount of coal that is assumed to be displaced by natural gas according to the EPA’s target setting calculations.

Wind power is a zero carbon energy resource that can help states achieve their emission rate reduction targets under the new EPA power plant carbon standard. Photo by Carlye Calvin.

And that is not likely to be the last of Colorado’s coal plant retirement decisions. A recent UCS analysis identified another 1,096 MW of economically vulnerable coal capacity in the state. If this capacity is also retired, the retiring generation would be equivalent to about 96 percent of EPA’s coal displacement building block. And, of course, thanks to the design of the EPA carbon rule, it doesn’t need to be replaced solely by natural gas. Other truly low carbon sources like renewables and efficiency could contribute as well, which would help minimize the significant economic and climate risks of relying too heavily on natural gas as a compliance option.

Deeper emission reductions are possible

With Colorado in such a strong position to comply with its targets in the draft rule; it begs the question of whether the target should be stronger? I believe the answer is yes, and not just for Colorado. For example, all states could achieve deeper reductions in emissions through more aggressive targets in the renewables building block. Colorado could also further strengthen its energy efficiency resource standard and take a closer look at whether it makes economic sense to continue operating some of its remaining coal plants.

These are some of the areas I’ll be focusing on in my testimony this week. Are you planning to attend one of the EPA’s public hearings? If so, what do you plan to say? If not, you still have the opportunity to submit written comments until October 16. Don’t miss out on the chance to voice your support for a strong carbon standard.