California’s transportation fuel policy is knee deep in cow poop, and it’s not a good look. The California Air Resources Board (CARB) is considering amendments to its Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) regulation, but indicated they have no plans to address the problems caused by counter-productive subsidies for manure biomethane. CARB’s use of the LCFS as a cash cow to fund manure digesters is bad transportation fuel policy and bad agricultural policy. Accounting gimmicks disguise a poorly run offset scheme as a magic carbon negative climate solution. CARB needs to phase out credits for “avoided methane pollution,” refocus the LCFS on transportation and get to work developing a more suitable regulation for pollution from dairies.

The immediate goal of the current LCFS rulemaking is to stabilize LCFS credit markets so that the policy can continue to provide much needed support for transportation electrification. LCFS credit markets are out of whack because the supply of credits is outstripping the demand. CARB has proposed to rapidly increase the stringency of the standard to increase demand for credits, but it should also address the supply of credits, to make sure the fuels supported by the LCFS help move California towards a clean transportation future.

A quick glance at the latest data from CARB shows there are three large and growing sources of credits: bio-based diesel, biomethane and electricity.

I’ve written recently about why a Cap on Vegetable Oil-Based Fuels Will Stabilize and Strengthen California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard, which addresses the bio-based diesel credits. The growing credits for electricity reflect the growing number of EVs on the road in California, and support California’s goal of phasing out combustion technologies in favor of zero emissions vehicles. But what about the rapidly increasing credits generated by biomethane? Vehicles powered by biomethane consume about one percent of California’s transportation fuel, but in the first three quarters of 2023, biomethane used to fuel these vehicles accounted for 17 percent of LCFS credit generation. The reason a small amount of biomethane generates such a large amount of credit is that biomethane gets credit not only for reducing transportation emissions, but also for reducing methane pollution from manure lagoons at dairies and hog farms across the United States. CARB does not break down the share of credits awarded for avoided methane pollution, but according to my calculations 85 percent of credits awarded by the LCFS in 2023 have nothing to do with transportation but are a poorly disguised offset program creating a gold rush of unverified claims of avoided methane pollution from manure lagoons.

A recent post by UC Davis economist Aaron Smith puts the question quite directly, Cow Poop is Now a Big Part of California Fuel Policy: Are the state’s new low-carbon fuel regulations full of BS? The short answer is yes, California’s approach to subsidizing manure digesters through its transportation fuel policy is a disaster, and California officials need to wind down a poorly run offset program that is going to cost California drivers at the pump without creating a viable long term strategy to address the problem of manure methane pollution from huge dairies.

For the last few years, I have been getting deeper into manure policy than I ever expected. My primary expertise is in lifecycle-based transportation fuel policy, which has recently been providing increasing financial support for biomethane generated from anaerobic digesters at dairy manure lagoons. For a legal perspective on the topic, read the report (and summary blog) by Ruthie Lazenby at UCLA’s Emmett Institute, for an economic perspective see Aaron Smith at UC Davis, and to understand the impact of pollution from massive dairies on the people that live in adjacent communities, read this article on How a California Dairy Methane Project Threatens Residents’ Air and Water.

In this blog, I will cover the following:

- Transportation fuel policies are based on lifecycle analysis.

- Negative carbon intensity scores are inconsistent with the LCFS and amount to an offset program.

- The LCFS manure methane offset program costs drivers more and delivers worse results than a similar policy designed to target dairy methane pollution.

- LCFS biomethane subsidies contribute to consolidation in the meat and dairy industry.

- California’s LCFS is causing problems for other states and the federal government.

The LCFS is designed to hold fuel producers accountable for their supply chain emissions

The LCFS and related Clean Fuel Standard policies are performance standards for transportation fuel based on lifecycle analysis. This is a little different than other similar sounding policies like Renewable Energy Standards, which can create some confusion. A Renewable Energy Standard requires utilities to source an increasing amount of the energy they generate or sell from renewable sources like wind and solar, heading towards a 100 percent standard that would reflect a 100 percent renewable grid with no further combustion.

But while a Renewable Energy Standard treats all sources of qualifying renewable energy equally, the LCFS has a more complicated approach, based on lifecycle analysis. Under the LCFS each fuel pathway gets a unique carbon intensity (CI) based on a lifecycle analysis of the greenhouse gas emissions associated with the production and use of the fuel. This approach originated from the recognition that many alternative fuels, especially ethanol, involve a lot of fossil fuels and other pollution in their production. When I started working on biofuel policy back in 2008, there was a lot of criticism of corn ethanol because in some cases it had lifecycle emissions higher than gasoline. This conclusion came from adding up the emissions from coal used to power the production process, natural gas-based fertilizer and diesel fuel used to farm and transport the corn and ethanol. To address this concern some folks at UC Davis and Berkeley had the idea of giving transportation fuels partial credit based on how much they reduced emissions on a lifecycle basis compared to gasoline or diesel. This, in a nutshell, is the logic of the LCFS. For more information on this type of policy see our page on Clean Fuel Standards.

Gasoline has a CI of about 100 grams carbon dioxide equivalent pollution per megajoule of fuel energy (g/MJ) once the emissions from extracting oil, refining it into gasoline and burning it in cars and trucks are added up. The CI of an electric vehicle charged with solar power is zero, and most of the biofuels fall somewhere in the middle1. This approach holds fuel producers accountable for reducing fossil fuel use and other global warming pollution in their supply chains. When the LCFS eventually gets to a carbon intensity of zero, you would think all the fuels used to power transportation should be zero carbon fuels. But unfortunately, this is where the implementation of the LCFS has drifted away from this idea of partial credit to hold fuel producers accountable for their own supply chains.

Negative CI scores are nothing more than a poorly regulated offset program

As Professor Smith explains in his latest cow poop post, California has been giving manure digesters large negative CI scores. “The carbon intensity of dairy [biomethane] ranges between -102.79 and -790.41 depending on characteristics of the digester. The current average carbon intensity for dairy [biomethane] is -269.” A negative CI score would suggest an almost magical climate solution that pulls several carbon dioxide molecules from the atmosphere for each one that comes from the tailpipe of a truck running on dairy biomethane. Unfortunately, this is far from the truth. The justification for negative CI scores is an assumption built into the lifecycle analysis that if the methane was not used as transportation fuel it would be emitted into the atmosphere. And because methane is such a potent heat trapping gas, credit for avoided methane emissions can be quite large.

Without the credit for avoided methane pollution the CI of dairy methane would be about 36 g/MJ2 instead of -269 g/MJ, which means that 85 percent of the credit claimed by dairy biomethane is associated with avoided methane pollution at the manure lagoon. Only 15 percent of the climate benefit assigned to dairy biomethane is associated with replacing fossil fuels with bio-derived fuel used for transportation3.

Blurring together the impact on transportation and agriculture creates confusion and leads to exaggerated claims of the benefits of manure digesters. Considered as a source of energy, anaerobic digesters are an expensive way to produce a small amount of energy. As Professor Smith explained in an earlier post, “the cost of an anaerobic digester is 10 times the market value of the gas it produces.” Dairy manure digesters are also an expensive strategy to mitigate methane emissions. More optimistic assessments of cost effectiveness ignore the multiple subsidies digesters receive, double (or triple) counting the climate benefits while understating the costs.

Professor Smith’s most recent blog explains that the main motivation to keep the avoided methane offset scheme in the LCFS is to continue to supply incentives to California dairy farmers to cover the high costs of installing and operating digesters as a means of reducing methane pollution from dairies.

Negative CI scores undermine California’s goal of phasing out fossil fuels and combustion fuels in general. Imagine a fleet of 7 diesel trucks in California, owned by a progressive company that wants to achieve carbon neutrality. Under existing LCFS accounting, this hypothetical company can convert 2 of its 7 trucks to run on compressed natural gas and contract with a manure digester to purchase the rights to match the fossil gas consumption of the trucks to the digester operator’s pipeline gas injection somewhere else in the continental United States (this is called book and claim accounting). According to the logic of the LCFS, the two biomethane fueled trucks now have negative emissions that more than offset the emissions of the 5 diesel trucks, so the fleet is notionally carbon neutral.

The key word here is offset. Obviously the 5 diesel trucks are still using fossil fuels and all 7 trucks are using internal combustion engines, creating tailpipe pollution that harms people in the communities in which the trucks operate. The claim embedded in the LCFS carbon intensity score is that avoided methane emissions from a manure lagoon offset the fossil CO2 emissions from the production and use of fossil diesel. Officially CARB claims that the LCFS includes no offset program. If it did, it would be subject to rules governing offsets that CARB would be required to enforce. I am not a lawyer, so I won’t venture a legal opinion, but from where I sit this is a distinction without a difference. A negative CI score is an offset because it allows continued use of fossil fuels in a regime that claims to achieve zero emissions.

Negative CI scores are inconsistent with the logic of holding fuel producers accountable for the fossil fuel use and global warming pollution in their supply chains. It flips this logic on its head by allowing fossil fuel producers to continue to sell fossil fuels by claiming credit for offsetting methane emissions reductions that are part of a milk or meat producer’s supply chain. And unfortunately, CARB’s insistence that it is not running an offset scheme keeps them from running it properly. Thus, the LCFS does not require evidence that claimed methane emissions reductions are real and additional, as would be required from any credible offset program.

Transportation fuel regulations are not the right tool to reduce dairy methane pollution

As a general rule, public policies are more effective when they directly address the problem they are trying to solve. The LCFS regulates oil refiners, who are primarily responsible for the production of high carbon intensity transportation fuel. The use of carbon intensity as a metric for the LCFS adds complexity, but it allows for a comprehensive approach to an increasingly diverse set of transportation fuels, including gasoline and diesel, various biofuels and different sources of electricity. The LCFS does not stand alone, but complements regulations that require car and truck manufacturers, fleets, and electric utilities to reduce pollution from their products and services.

The primary business of dairies is to produce milk rather than transportation fuel, so using the LCFS to reduce pollution from dairies is quite indirect. To illustrate the problems caused by this indirect approach, consider how things would be different if the LCFS were adapted to directly target dairy pollution by creating a Low Carbon Milk Standard that operated alongside the LCFS. This hypothetical Low Carbon Milk Standard would resemble the LCFS but focus on milk rather than gasoline and diesel. It would assign a carbon intensity score to milk sold in California and set a steadily decreasing standard for the industry. I shared this idea with CARB staff and leadership last August, to help explain why focusing regulations on methane mitigation would be a better strategy to meet California’s methane goals than subsidizing manure biomethane production through a poorly run offset program.

Benefits of a Low Carbon Milk Standard (or other agricultural methane regulations)

Just as the LCFS is based on the supply chain emissions of transportation fuel per unit of energy, a low carbon milk standard (LCMS) would be based on the supply chain emissions per unit of milk. While structurally similar, the milk supply chain emissions would include all the emissions associated with milk production, not just the manure, and would apply to all milk producers, whether they use a digester to capture and sell biomethane or use a different manure management strategy that minimizes the production of methane in the first place.

Under the LCFS, credits are only awarded for biomethane that is captured and used for fuel, and it is presumed that this methane is an inevitable consequence of milk production. Under a LCMS, there is no need for any such presumption, and all strategies that reduce methane pollution are treated equally. This avoids distorting the market for methane mitigation in favor of more polluting manure management strategies. California has an alternative manure management program (AMMP), that provides financial assistance for the implementation of non-digester manure management practices including composting and conversion to or expansion of pasture-based systems. These practices reduce climate pollution and provide other air and water quality benefits. Under the LCFS, dairies that use AMMP practices are at a competitive disadvantage compared to dairies that use digesters and can generate a substantial revenue stream from selling manure to operators of the digesters.

Opponents of dairy regulations claim that if California enacts stricter regulations on dairies than other states, dairies may just leave California, continuing to pollute but outside the reach of California regulations. This is called emissions leakage, and is discussed by both Ruthie Lazenby and Aaron Smith. The LCMS addresses leakage in the dairy sector the same way the LCFS does in the fuel sector. Out-of-state milk producers would be held to the same standards for pollution as California producers. The LCFS has survived legal challenges, and the same arguments should apply to an LCMS.

An LCMS would also address arguments that phasing out LCFS credits for avoided methane pollution would cause digesters to shut down, making it harder for California to meet its methane pollution targets. Digesters would continue to operate to meet the LCMS standard unless the dairies found a more cost-effective way to mitigate methane. Digesters make the most sense economically at large dairies, and at these facilities digesters would likely remain a cost-effective way to meet LCMS obligations. They can even keep selling biomethane to displace fossil gas, but the biomethane would not be credited with avoided methane emissions within transportation fuel or other energy policies.

Regulating manure methane directly would save California drivers money

The California LCFS is designed to support the production of low carbon transportation fuel, and it applies the same lifecycle analysis methodology to all fuels, regardless of where they are produced, so long as they are used in California. As previously described, biomethane is allowed to use book and claim accounting. As a result, manure digesters at both dairies and swine concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) all over the country have been granted LCFS pathways to produce biomethane with large negative CI scores. This means that California drivers are being asked to bear the cost of large subsidies for milk and meat producers nationwide, even though any reductions in methane pollution will not reduce California’s emissions.

Regulating pollution from dairies through an LCMS or other regulation would shift the costs of reducing methane pollution to milk producers, and these costs will presumably be passed along to milk consumers. But these costs are likely to be quite a lot lower than current LCFS costs for three reasons. The LCFS is subsidizing manure digesters at dairy and swine CAFOs across the United States while the costs of a regulation would be limited to milk produced and/or sold in California, depending on the structure of the regulation. Second, a regulation developed for dairies should support a wider set of practices and technologies to mitigate pollution suitable for different types of dairies, which should bring down costs compared to limiting support to expensive digesters with gas cleanup and injection required to sell biomethane. And finally, a well-designed regulation should reduce the windfall profits that have accrued to biomethane developers selling credits into LCFS markets.

LCFS biomethane subsidies create a gold rush available only to very large farms, which encourages dairy (and meat) industry consolidation and distorts food markets

LCFS credits for avoided methane are one of several sources of support for digesters, with additional support coming from the Federal Renewable Fuels Standard Program (RFS) and grants from California’s Department of Food and Agriculture and programs from the US Department of Agriculture. Professor Smith has analyzed how profitable these subsidies are in detail in his recent post.

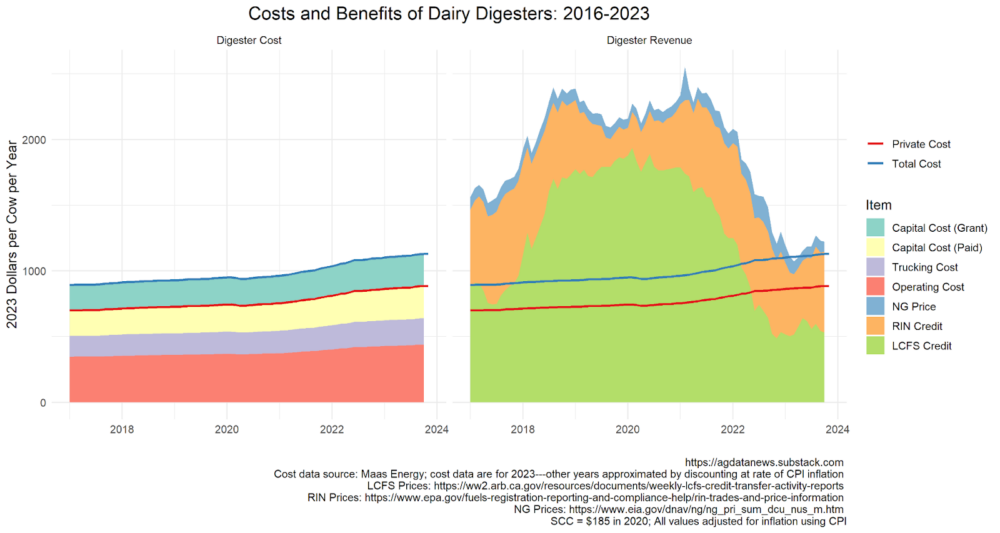

Between mid 2018 and the end of 2021, revenues from selling biogas and the associated [RFS credits, called RINs] and LCFS credits were approximately double the cost of installing and running a typical digester, as shown in the figure below. LCFS credit prices have declined in the last two years, making the typical digester closer to a break even proposition. If and when credit prices go back up, then the profits will return.

There has been an extensive coverage of the gold rush these generous subsidies started, in trade press and even the Wall Street Journal, which headlined its piece “California’s Green-Energy Subsidies Spur a Gold Rush in Cow Manure: A lucrative state incentive to make natural gas from dairy waste is attracting companies from Amazon to Chevron.”

These extremely profitable subsidies also contribute to consolidation. Building and operating a digester and the equipment required for gas cleanup and pipeline injection is very expensive, and even with large subsidies is generally only economic at very large dairy and swine CAFOs. At the largest CAFOs, the payments a farmer receives from a digester operator can be a significant portion of their income. But digesters generally don’t make sense on smaller farms, because without thousands of cows or pigs, there is just not enough poop to make a digester and gas collection cost effective.

Smaller facilities can use other manure management strategies that reduce methane production in the first place or capture and flare methane, but since these strategies don’t result in methane to sell to energy markets, they are excluded from LCFS biomethane subsidies. If digesters really were efficient producers of transportation fuel, LCFS support would make sense. But in reality, 85 percent of the LCFS subsidy is based on claims of avoided methane pollution, so excluding other strategies that can also avoid methane pollution distorts the lucrative market for avoided methane pollution by disguising it is a market for transportation fuel. This means that the largest dairies have preferential access to a lucrative revenue stream that is decoupled from the low margin high risk business of selling milk.

A 2020 report from the US Department of Agriculture on Consolidation in U.S. Dairy Farming highlights that “[t]he number of licensed U.S. dairy herds fell by more than half between 2002 and 2019, with an accelerating rate of decline in 2018 and 2019, even as milk production continued to grow.” Several factors contribute to consolidation, and there is a heated argument over the evidence that LCFS subsidies have played a significant role. The basic economic arguments are clear enough. While key details are contested and not all the relevant data is publicly available, there is no real dispute that the LCFS biomethane subsidies have been a boon to large CAFO dairies and exclude smaller farms. This insight is not limited to opponents of the digesters and can also be found in the dairy trade press. A 2021 article explains the unintended consequences as follows:

The net effect will be that dairy farms with methane digesters and other green energy technologies will make decisions based more on returns from energy than returns from milk. It fundamentally changes dairy farm economics as well as milk and dairy product prices. If this comes to fruition, dairy market signals to raise or reduce milk production will be less effective. This could lead to a structural oversupply of milk in the domestic market[…].

Michael McCully. Hoard’s Dairyman. 2021

Structural oversupply in the milk market would certainly be hard for dairies without digesters whose business is limited to selling milk and are excluded from the LCFS biomethane gold rush.

The dispute is over the evidence that LCFS biomethane subsidies have already caused consolidation and how the role of the LCFS can be disentangled from other factors. The data question is complicated by the fact that key statistics are published only every 5 years. Until this week, the most recent data was from 2017, and comparing 2012 to 2017 does not say much about LCFS supported digester boom, which mostly happened after 2017. The data from the 2022 USDA Agriculture Census was released on February 13th and it confirms that dairy consolidation in California is continuing. The share of dairy cows in California on farms of 2500 cows or more grew from 46 percent in 2017 to 61 percent in 2022. Disentangling the role of the LCFS from other factors is beyond my expertise, so I am looking forward to reading what the experts have to say about it.

California’s bad biomethane policy is causing problems across the United States

I work on transportation fuel policies across the United States. For several years I have been part of a Midwestern Clean Fuels Policy Initiative, and I have been working with Minnesota-based non-profits to develop a clean fuel policy for Minnesota. I was recently part of a Clean Transportation Standard Work Group run by the Minnesota Department of Transportation. The members of the work group have diverse perspectives on many things but agree that Minnesota should not copy California’s LCFS but learn from it and create a policy that makes sense for Minnesota. Several Minnesota groups I have spoken with have major concerns that California LCFS subsidies for digesters are driving small dairies out of business. This is a very real concern in Minnesota, which ended in 2023 with 146 fewer dairy farms than it had at the beginning of the year. But a major challenge to crafting a Minnesota specific policy is that the largest dairies in Minnesota, run by a company called Riverview Farms, are already enrolled in the California LCFS. The result is that California drivers are spending increasing amounts of money to subsidize digesters in Minnesota in a manner that distorts dairy markets in Minnesota and is largely outside the control of Minnesota voters or policymakers.

The problem arises from treating manure digesters as a source of magic negative carbon energy instead of recognizing that their primary climate benefit is pollution mitigation from manure lagoons. Digesters do not pull methane out of the atmosphere; they capture methane that was created by the deliberate choice to collect and store manure in anaerobic conditions in huge lagoons. The idea that manure methane is uniquely valuable is leading to proposals from the biogas developers to truck manure from smaller farms to a central digester so that they too can participate in the digester gold rush, or to figure out how to install digesters at beef cattle feedlots that currently use dry manure management.

Crediting methane collected from these projects as if it is an inevitable consequence of manure management and assuming it would otherwise be vented into the atmosphere is clearly wrong from a technical perspective. It also sends a signal to farmers that they should get into the energy business and “get big or get out,” in the infamous words of Nixon’s Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz. Most policymakers now recognize the harmful consequences of this attitude, so they should make sure their policies support their stated goals.

Decisions about the most suitable strategy for manure management are complex and depend on many local factors that affect not only the farm’s profitability but also the local environment and community. These decisions should not be dominated by the results of a lifecycle analysis spreadsheet developed for a California transportation fuel regulation that only values “avoided methane pollution” when it is associated with transportation fuel production. If policymakers want to provide support to help farmers reduce methane pollution, they should provide at least equivalent support for methane pollution that is actually avoided because it was never created. When energy policy and agricultural policy intersect, we should make sure the results are supporting good outcomes in both spheres, and the California LCFS credits for avoided methane pollution are clearly failing that test.

What started as a clever way for California regulators to indirectly support expensive dairy digester projects in California is putting smaller farms across the United States at a disadvantage, especially those that use more sustainable manure management strategies, and potentially pushing them out of the business entirely. The problem is not limited to transportation fuel policy, it is also setting a damaging precedent that threatens to undermine the integrity of numerous new lifecycle-based tax credits, including the federal clean hydrogen production tax credit .

Agricultural methane policy should help food producers reduce pollution rather than paying for poop

Real harm results from disguising manure digesters as a magic negative carbon energy technology. Reducing pollution from food production is important, and so is scaling up renewable energy production to replace fossil fuels. Connecting these goals with a de facto offset regime is creating a lot of problems, and we need a better approach.

Policy makers must ensure that regulations and incentives shaping our food system not only address methane pollution from sources like manure lagoons but build a better food system—one that provides healthy, sustainably produced food for all and treats everyone at every stage of the system fairly. This is a big task, which can seem daunting and unrealistic. The magnitude of the challenge leads some to argue digester subsidies, by whatever means they can be financed, are a justifiable short-term expedient to address an urgent problem. But California’s de facto offset regime is doing more harm than good, undermining California’s transportation fuel policy, distorting milk and meat markets across the country in favor of the largest producers of manure and setting a damaging precedent that could undermine federal support for hydrogen or any other policy based on lifecycle analysis.

Negative carbon intensity scores have no place in transportation fuel policies. These policies should support the transition away from fossil fuels and hold all fuel producers accountable for pollution in their supply chains. The California Legislature gave regulators authority to start regulating dairy pollution in 2024, and they should start developing these regulations. My hypothetical Low Carbon Milk Standard illustrates the major structural problem with the LCFS biomethane offset program that is fixed by refocusing dairy methane policy on the primary polluter. But real policies that affect agriculture should be designed to meet the needs of farmers, farm communities and the environment, and not copied directly from the energy or transportation fuel sector.

Policymakers outside of California should understand that supporting methane pollution reduction using lifecycle analysis accounting gimmicks can seriously backfire and hurt small farms. Any policy that aims to reduce pollution from milk (or meat) production, whether as part of a regulation or an incentive, must be designed to reduce methane pollution, rather than to increase biomethane use. Fixing our broken food system requires a more thoughtful approach that grapples with the realities of the system, rather than just throwing money at the largest polluters.

- For more on the carbon intensity of transportation fuels, see my 2016 report, Fueling a Clean Transportation Future. For more technical discussion on lifecycle methodology issues, see the report of a 2022 National Academies committee on which I served, Current Methods for Life-Cycle Analyses of Low-Carbon Transportation Fuels in the United States. ↩︎

- O’Malley, J., N. Pavlenko, Y.H. Kim. 2023. 2030 California Renewable Natural Gas Outlook: Resource Assessment, Market Opportunities, And Environmental Performance. ↩︎

- This calculation is based on average carbon intensity of a dairy digester of -269, as reported in Aaron Smith’s January 2024 post, the 2024 LCFS standard for diesel of 87.89 g /MJ and a carbon intensity of 36.4 g/MJ for dairy biomethane without avoided methane credits, per O’Malley, J., N. Pavlenko, Y.H. Kim. ↩︎