Faithful readers will have seen my data-based analysis of the US mandates for biofuels under the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) big choices on how to administer the program looking ahead. These choices highlight how the “food versus fuel” debate extends far beyond corn. The bottom line is that if the agency expands the RFS advanced mandate to make up for the slow commercialization of non-food “cellulosic” fuels, it will undermine the environmental and fuel security goals of the fuel standard, and contribute to food supply problems worldwide.

This post is part of a series on The Future of Biofuels.

This post is part of a series on The Future of Biofuels.

There are two potential sources of biofuel large enough to fill the cellulosic shortfall, sugarcane ethanol from Brazil, and biodiesel made from vegetable oil or animal fats. On Tuesday I analyzed what it would mean to have sugarcane ethanol fill the void, and today I will cover biodiesel.

Biodiesel: fuel from fat

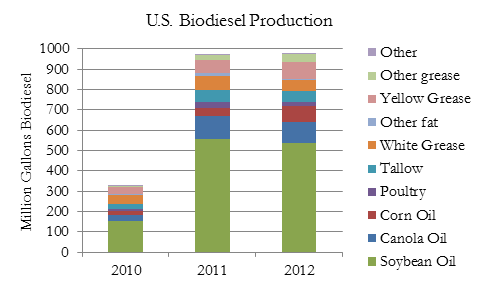

Biodiesel is produced from a variety of sources of fats and oils, and production has expanded rapidly over the past few years. When made from your local McDonald’s waste French fry oil, biodiesel is a low impact, low-carbon fuel. However, when demand for biodiesel production exceeds the low impact sources of fats and oils, serious problems can arise.

EPA has already expanded the biodiesel mandate for this year, from 1 billion gallons in 2012 to 1.28 billion gallons for 2013. But it looks increasingly likely that biodiesel could exceed the biodiesel mandate to also fill the cellulosic shortfall for the year, primarily because Congress included an extension of the $1/gallon biodiesel tax credit as part of the fiscal cliff tax changes.

Where does the vegetable oil come from?

As the biodiesel mandate has grown, so has the use of food grade vegetable oils such as soybean oil. When added up, food grade vegetable oils account for about two thirds of biodiesel production, with various other fats and oils making up the remainder. According to the projections from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the use of vegetable oil to make biodiesel in the U.S. over the last few years nearly matches an expanding gap between imports and exports, and this is a trend expected to continue (note that 2 million metric tons of vegetable oil is about enough to make about 550 million gallons of biodiesel).

So if increased biodiesel use is leading to increased reliance on imported vegetable oil, we need to look overseas to see where the real impact lies. And the largest and fastest growing source of global vegetable oil exports is palm oil from Southeast Asia.

The long winding road to Southeast Asia

Palm oil is also the cheapest, which makes it highly likely that whether or not it is directly imported into the U.S., palm oil will ultimately make up for the oils and fats used to make biodiesel.

Peat forest cleared or oil Palm, Sarawak Malaysia Flickr/Wakx

The area used for palm oil production has doubled in just a decade. Since palm oil will ultimately be the source of oil that indirectly replaces the oils and fats required to fill an expanded biodiesel mandate, it is likely that expanding the advanced mandate will not meet the 50% GHG emissions reductions requires of advanced biofuels, and may not reduce emissions at all. Palm oil is associated with a host of disquieting problems, mostly about draining peat swamps and cutting down forests to expand plantations, at great cost to orangutans, local people, and the global climate. EPA also assessed the impact of palm oil biodiesel last year, and EPA’s preliminary finding was that the lifecycle impacts of palm oil based biofuels do not even meet the minimum 20% threshold (greenhouse gas reductions compared to gasoline) required for biofuels under the RFS, although I think EPA actually underestimated the impact. In other words, this stuff is worse than corn ethanol.

Before I close I want to reiterate that there are low carbon sources of biodiesel. Displacing fossil fuels with oils and fats recovered from our waste stream is clearly a smart move. At an appropriate scale there may be oil crops that make sense as well. But even the lower mandate levels EPA is considering (what I called the 20BG + RFS in my earlier post) draw considerably against these resources. The low carbon oils and fats are simply not available at a quantity consist with the larger 36BG RFS, and if we ramp up demand too fast, we will draw in damaging resources like palm oil that will undermine the long terms goals of the RFS.

Make your voice heard

Overall, these past couple posts illustrate that EPA faces a critical decision in administering our nation’s biofuel policy. EPA can focus on the 36BG target, regardless of the consequences, or allow the advanced mandate to grow in a manner that adheres to the original goals of the RFS, promoting clean, sustainable biofuel. These three blogs cover much of the substance of comments UCS will be filing with EPA.

You can also help EPA make a smart choice by submitting comments to the rule by going to regulations.gov and submitting comments on Docket ID No. EPA–HQ–OAR–2012–0546 before the comment period closes on April 7th. Together, we can make sure EPA gets the picture. Thanks for your help.

Learn more about the future of biofuels

- The Future of Biofuels in 10 Charts and Maps

- Great Scott! The Consequences of Accelerating the Mandate for Food-Based Advanced Biofuels

- The Food Versus Fuel Fight Is About Much More Than Corn

- The Coming Fork in the Road for Biofuels