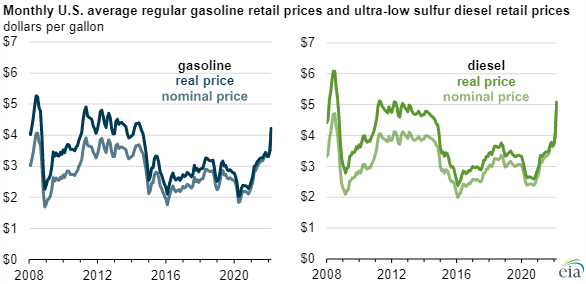

When gasoline prices rise, as they have since the winter of 2020, or spike dramatically, as they have with the war in Ukraine, people naturally want to know why it happened and what we should do about it.

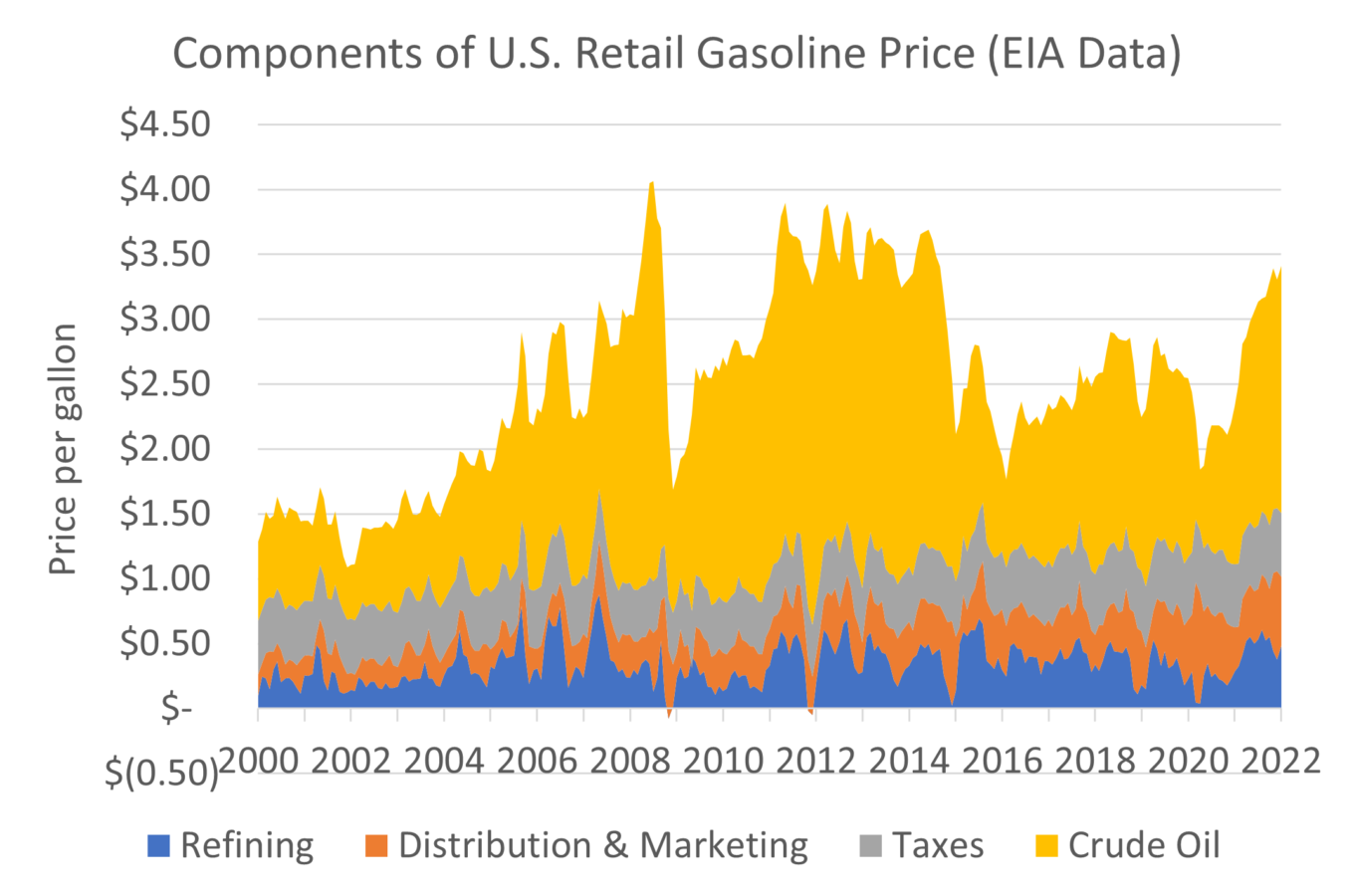

The basics of gasoline prices are no mystery, with lots of useful information available from the Energy Information Administration (EIA). The largest component of gasoline prices and the main source of price volatility is the cost of crude oil, which made up 55% of the cost of a gallon of gas over the last decade. Crude oil is what oil companies drill for and extract. Oil is then sent to oil refineries to make fuel and other products (like chemicals and asphalt). The other contributions to the cost of a gallon of gasoline are refining costs and profits (14%), gasoline distribution and marketing (14%), and federal and state taxes (17%). Looking at how these have changed over the last couple decades, it’s clear that the cost of crude oil is responsible for most of the volatility, although refining costs are also volatile, even occasionally dipping into negative values for brief periods.

Oil production, consumption and distribution

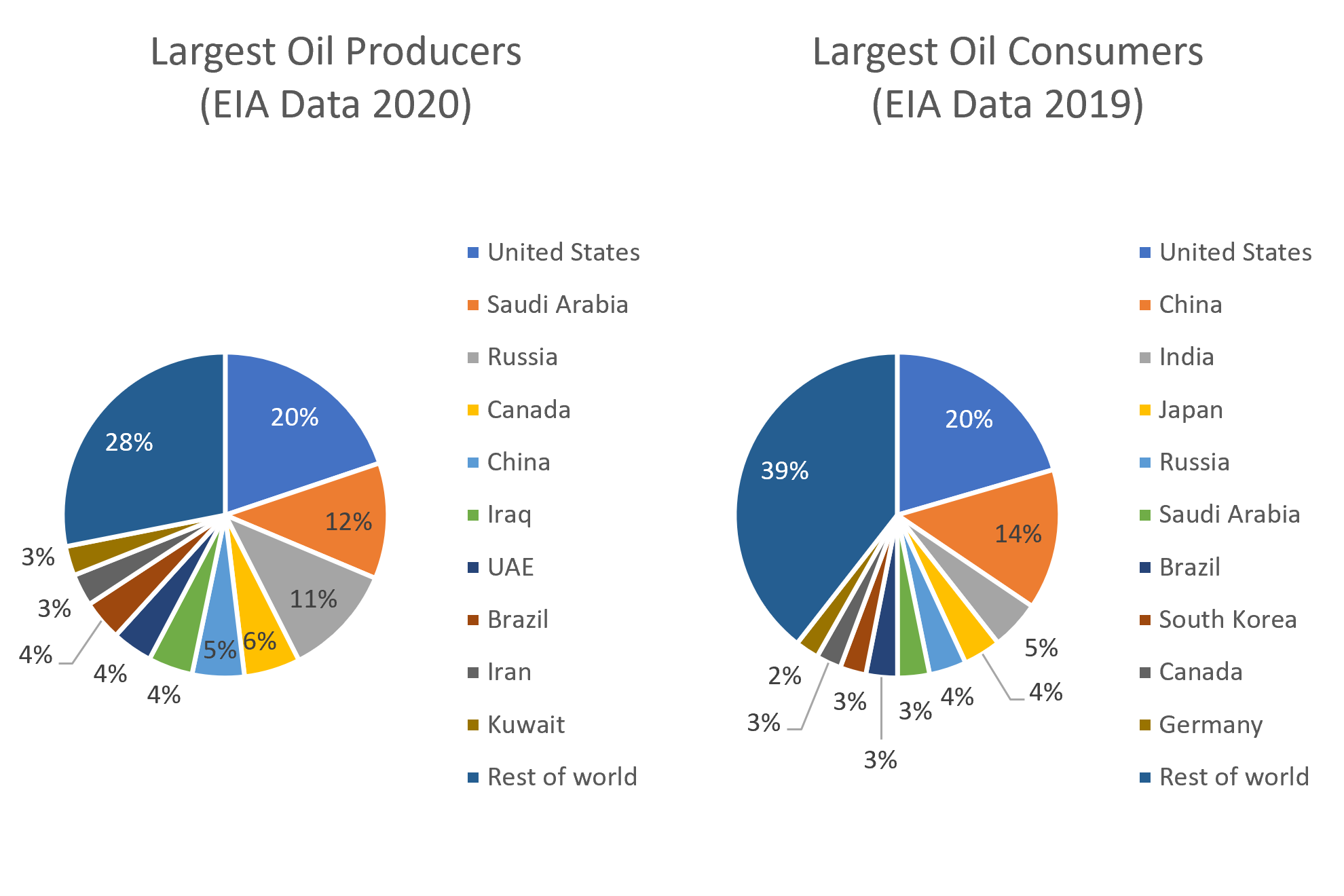

The US is the largest oil producer in the world, accounting for about a fifth of total global oil production, but it is also the largest consumer of petroleum products and consumes about the same amount it produces. Despite being “energy independent” on a net basis, the US imported about 40% of the crude and petroleum products it consumed in 2021 and exported a similar amount. It might seem strange that the US would import and export the same product, but different kinds of oil have very different properties, and different refineries are set up to process certain types of crude. This, plus the configuration of pipelines and other infrastructure, lead to lots of imports and exports of what is a very global commodity. This global nature of oil markets also means that US consumers remain vulnerable to changes in oil prices across the globe.

Many of the large oil producing countries are part of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) which describes itself as “a permanent intergovernmental organization of 13 oil-exporting developing nations that coordinates and unifies the petroleum policies of its Member Countries.” These include Saudi Arabia, Iraq, United Arab Emirates, Iran, Kuwait, Nigeria and Venezuela. According to EIA, OPEC members produce about 40 percent of global crude oil, and about 60 percent of total petroleum traded internationally. OPEC seeks to influence global oil prices by setting production targets, although member countries do not always comply with the targets adopted by the organization. Geopolitical conflicts and internal political turmoil within OPEC member nations and other oil producing countries can all end up affecting the global supply and price of crude oil.

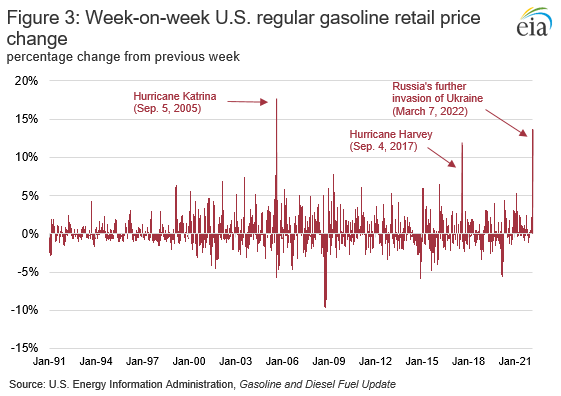

At the other end of the supply chain, disruptions at refineries, from explosions to hurricanes, can also have a major impact on short term gasoline prices, interrupting oil refining and distribution of the transportation fuels consumers buy. This is illustrated in the chart below from EIA which shows hurricanes that interrupted oil refining in the Gulf of Mexico having a short-term impact on retail gasoline prices comparable to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The reason for volatile prices, inflexible supply and demand

Both the supply of crude oil and demand for petroleum products like gasoline, diesel and jet fuel, are relatively inelastic, meaning that a relatively large change in price leads to a relatively small change in supply and demand, especially in the short term. In simple economic terms, we expect prices to provide a key connection between supply and demand. So if there is suddenly an interruption in the supply chain that reduces supplies of oil or gasoline, prices rise until demand drops as much as supply. But it takes a relatively large increase in prices to reduce demand. The same is true of supply, with large changes in price leading to relatively small changes in supply, especially in the short term. Small disruptions in supply can be covered by selling oil that is stored by private companies or held by the government in the strategic petroleum reserve. But the scale of oil exports from Russia is much larger than can be covered by oil in storage, so the price is surging.

On the supply side, you would expect oil companies to respond to higher prices by extracting more oil. Some increases in production are already happening, but it takes months to years for actions oil companies take today in response to higher prices to result in increased production. And the companies know that by the time the increased production comes to market, prices may have fallen again, especially if they dramatically increase production. The main reason oil company executives currently say they are hesitant to increase production is “investor pressure to maintain capital discipline,” which means avoiding another boom-and-bust cycle like the many that have come before. So, the actions (or inaction) of oil companies are based on their medium to long term expectations about oil prices rather than today’s prices. This is why petroleum supply is considered relatively inelastic in the short term.

Similarly, on the demand side, we’d expect fuel consumers to use less gasoline when prices rise, and they do. But it is hard for consumers to quickly make big changes in their behavior to reduce fuel demand. People can reduce their driving by combining trips, walking, biking or exploring transit options they might have overlooked when fuel prices were low , and those are very good ideas. They might also think twice about taking a long road trip. People might think about trading in that gas-guzzling SUV for a fuel-efficient hybrid or an electric vehicle. That’s a great medium to long-term fix, but it is not a short-term solution to a gasoline price spike, especially with COVID supply chain issues reducing the supply of new and used cars of all kinds and increasing prices. In the short term, the choices people have to reduce gasoline consumption depend on where they live, what kind of car or cars they own, if any, whether they have access to transit or safe places to ride a bike, and it’s hard to make dramatic changes quickly. Thus, petroleum demand is relatively inelastic in the short term.

The only sure solution to the many other problems caused by oil is to stop using so much oil

While it’s hard to dramatically reduce petroleum fuel consumption in the short term, either as an individual or a nation, there are lots of great oil saving solutions in the medium and long term, and the time to get started is now! While most people can’t replace a gas guzzler in response to a short-term price spike, buying an EV or more efficient car the next time you are in the market can help insulate you from future price shocks. EV’s cost less to operate, and electricity prices are far less volatile than gasoline. EVs are already cleaner than gasoline vehicles, and as the grid gets cleaner the pollution associated with charging an EV will continue to fall.

And the pain in the pocketbook imposed by high has prices is just the tip of the iceberg of harm caused by oil. Petroleum is the largest source of global warming pollution in the United States, and harms people and communities exposed to pollution from oil extraction, from oil refineries or from tailpipe pollution from burning gasoline and diesel in cars and trucks. Further from home, the trillions spent on oil each year prop up autocrats across the world. Steadily phasing out our use of oil will not only free us from price volatility and pollution but cut off the flow of funds to these bad actors.

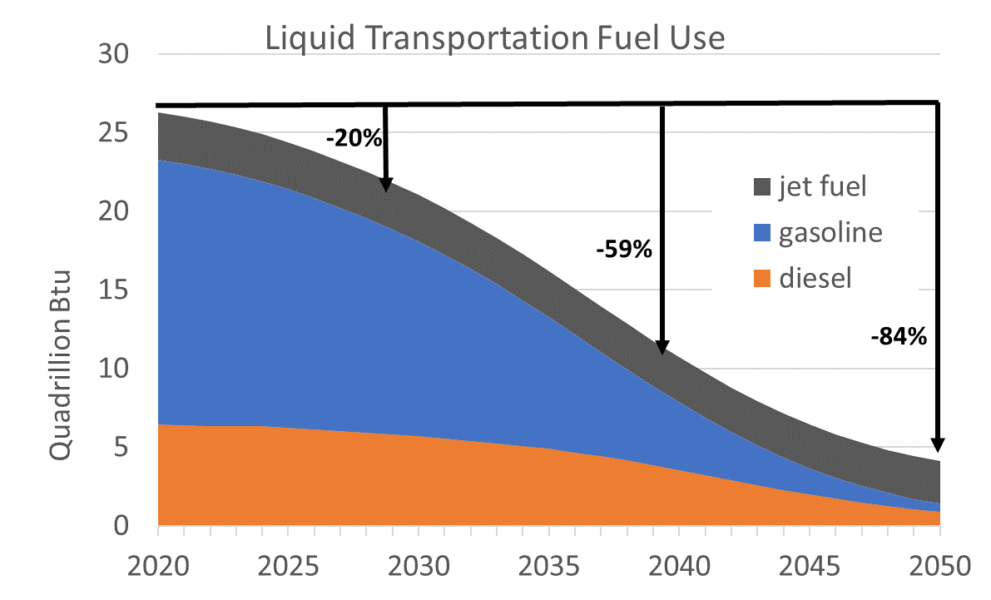

A recent UCS analysis examined pathways for meeting carbon reduction requirements in line with the Paris Agreement through 2050. A big piece of that is replacing petroleum with renewable electricity as the main source of transportation energy. Our analysis looked at one ambitious but feasible scenario where the transition from petroleum involved getting to 100% electric vehicle sales by 2035 for cars and by 2040 for trucks, which would reduce the combined use of gasoline, diesel and jet fuel by 20% by 2030, 59% by 2040 and by 84% by 2050. By then, jet fuel rather than gasoline will be the primary source of liquid transportation fuel demand and meeting it with low carbon alternative fuels will be far more manageable than replacing all current uses of petroleum fuel.

Replacing gasoline-powered cars and diesel trucks with battery electric and hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles is core to phasing out petroleum, but it is far from the only way we can and should cut oil use. Investing in public transit and walking and bike infrastructure, building our communities so that people can get around without getting in a car, making sure that the remaining internal combustion vehicles are as efficient as possible and developing low carbon alternative fuels are all important to fully phasing out oil as quickly as possible. And every step of the way means less oil use, less pollution, and less harm to our economy from oil price volatility.