Burning coal to produce electricity leaves behind coal ash, one of the largest industrial waste streams in the United States. Coal ash contains more than a dozen toxic substances that threaten public health and the environment, and weak regulations and lack of enforcement have allowed the ash to pollute our air, soil, and waterways.

But there is good news. Comprehensively cleaning up coal ash waste would ensure long-lasting environmental benefits and address environmental justice issues as well as generate new jobs in communities where coal-fired power plants have closed and expand opportunities for community redevelopment.

A new report by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) and the Ohio River Valley Institute, Repairing the Damage: Cleaning Up Hazardous Coal Ash Can Create Jobs and Improve the Environment, highlighting the environmental and economic benefits of cleaning up coal ash at sites in Ohio and Kentucky, shows how these benefits could be achieved.

Coal ash cleanup is a national problem

Local communities—often low-income communities and communities of color—have for decades borne the brunt of the impact of coal ash, including polluted air and water and workplace illnesses and deaths. Research by Earthjustice has documented the extent of coal ash pollution. And our new work builds on previous work by the Northern Plains Resource Council, the Environmental Integrity Project, and Earthjustice that quantified the benefits of coal ash cleanup at three other sites nationwide.

Coal ash—or coal combustion residuals—is made up of a variety of waste streams, including fly ash, bottom ash, boiler slag, and material from flue gas desulfurization. While coal ash can be reused in such products as concrete, power plant owners responsible for the waste typically dispose of it on site, and often mix it with water to create a slurry and then pipe it to a nearby coal ash pond. Coal ash ponds, which are designed to contain many decades’ worth of waste, average more than 50 acres in size and more than 20 feet deep. Owners also store coal ash in dry form in landfills or reuse it for other industrial applications.

The new UCS-Ohio River Valley Institute report evaluates the cleanup costs and job-creation potential at two coal ash sites, the first case studies of their kind for the Ohio River Valley. One site, the J. M. Stuart coal-fired power plant in Adams County, Ohio, closed in 2018 along with another nearby coal plant, dealing a significant blow to the local economy. The other site, the Sebree Generating Station, consists of three coal-fired power plants (one still in operation but slated for retirement) in Webster County in western Kentucky. Our analysis evaluates the two sites owners’ plans for cleanup activities (both of which are violating federal regulations) and proposes a more complete “clean closure” plan for both. We conducted an engineering analysis to estimate the costs and direct job creation from the cleanup proposals for each site and used those results to perform an economic analysis of the impacts of the projects on each state’s economy.

Proposed cleanup plans are inadequate

Our team’s engineering analysis revealed problems at both sites. At Sebree, the utility plans to close its disposal sites between 2022 and 2024 by covering them and leaving the coal ash in place. This would likely be ineffective in preventing ongoing pollution. Its plan to cover the two coal ash ponds would not address known groundwater contamination issues and would violate the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) 2015 Coal Combustion Residuals Rule, which prohibits capping an impoundment in place when ash is in contact with groundwater. If left in place, the contamination from the coal ash ponds would continue indefinitely.

Meanwhile, three of the ponds at J.M. Stuart violate location restrictions because of their proximity to a local aquifer and are contaminating groundwater, according to the owner’s own reporting. Failure to comply with federal groundwater monitoring requirements also has resulted in critical gaps in data for the rate and direction of groundwater flow and uncertainty regarding the nature and extent of the contamination both onsite and offsite.

Clean closure is better for the environment and the economy

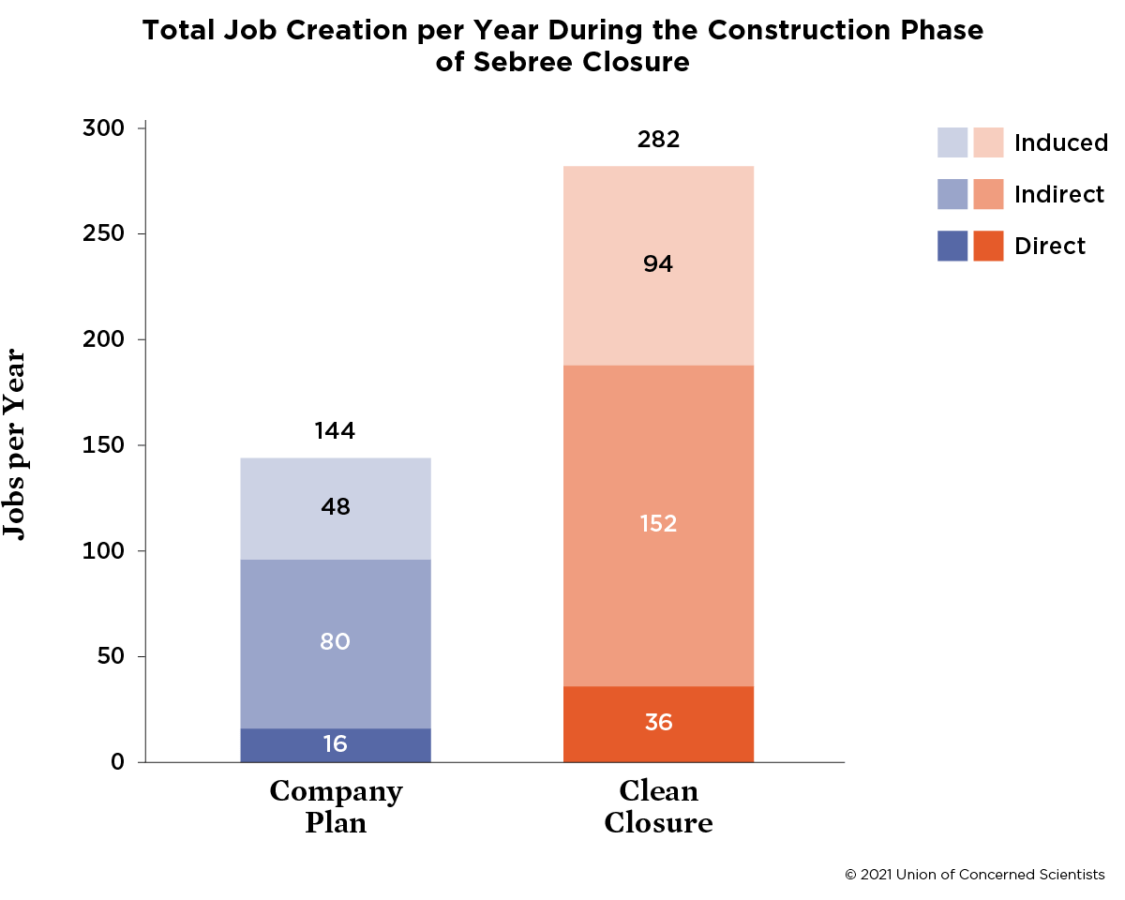

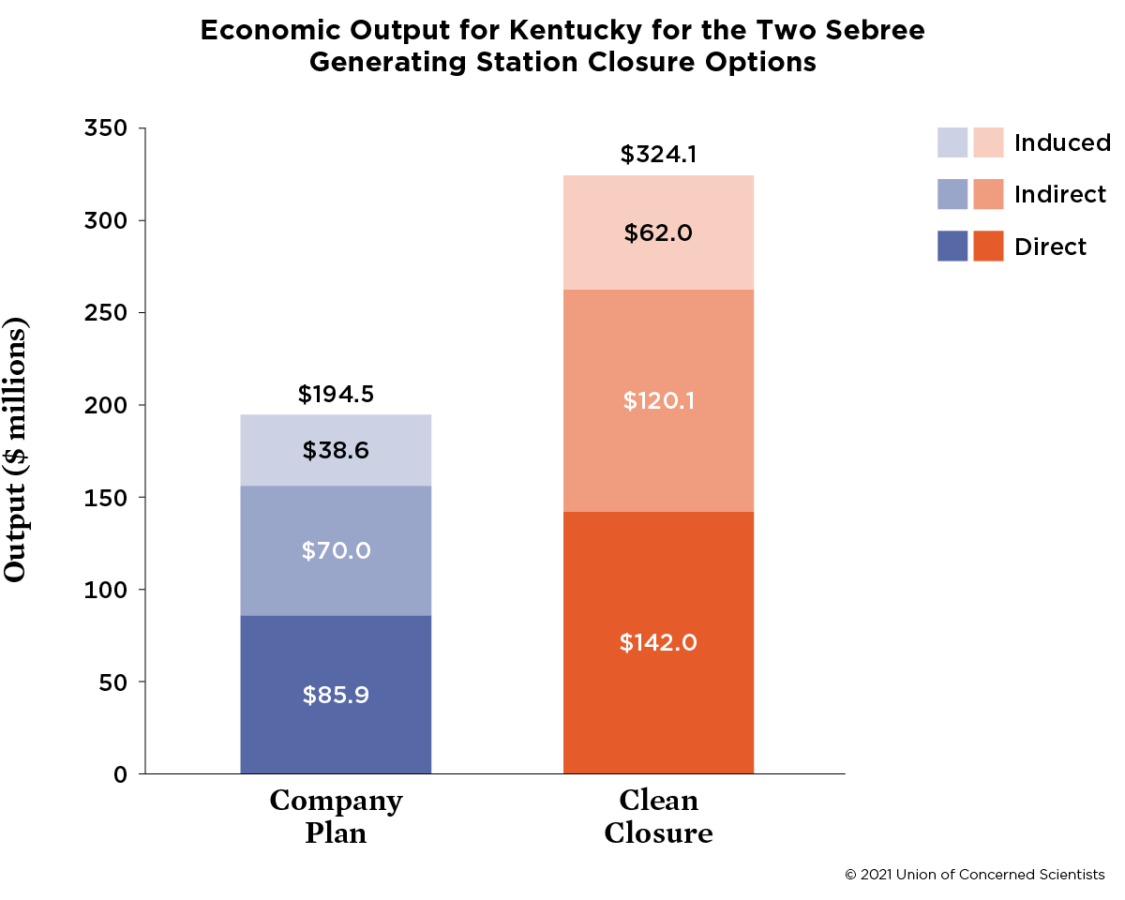

Our proposed clean closure options for both sites include excavating and properly disposing of all accessible coal ash waste. We found that clean closure would provide superior protection for public health and the environment and create better opportunities for local jobs and associated economic activity, which is consistent with previous analyses conclusions. The additional costs of clean closure are justified by the higher number of jobs, broader economic benefits, and potential for redevelopment for nearby communities. These benefits would be especially significant for the Sebree plant, where the clean closure plan would generate nearly twice as many jobs as the utility’s proposal during the project’s construction phase, which refers to initial investments in infrastructure needed to excavate and safely store the coal ash waste. Clean closure would create 282 jobs during the four-year construction phase, while the utility’s plan would create 144. The clean closure option also would generate $130 million more than the owner’s plan in economic activity over 34 years (four years of construction plus 30 years of monitoring).

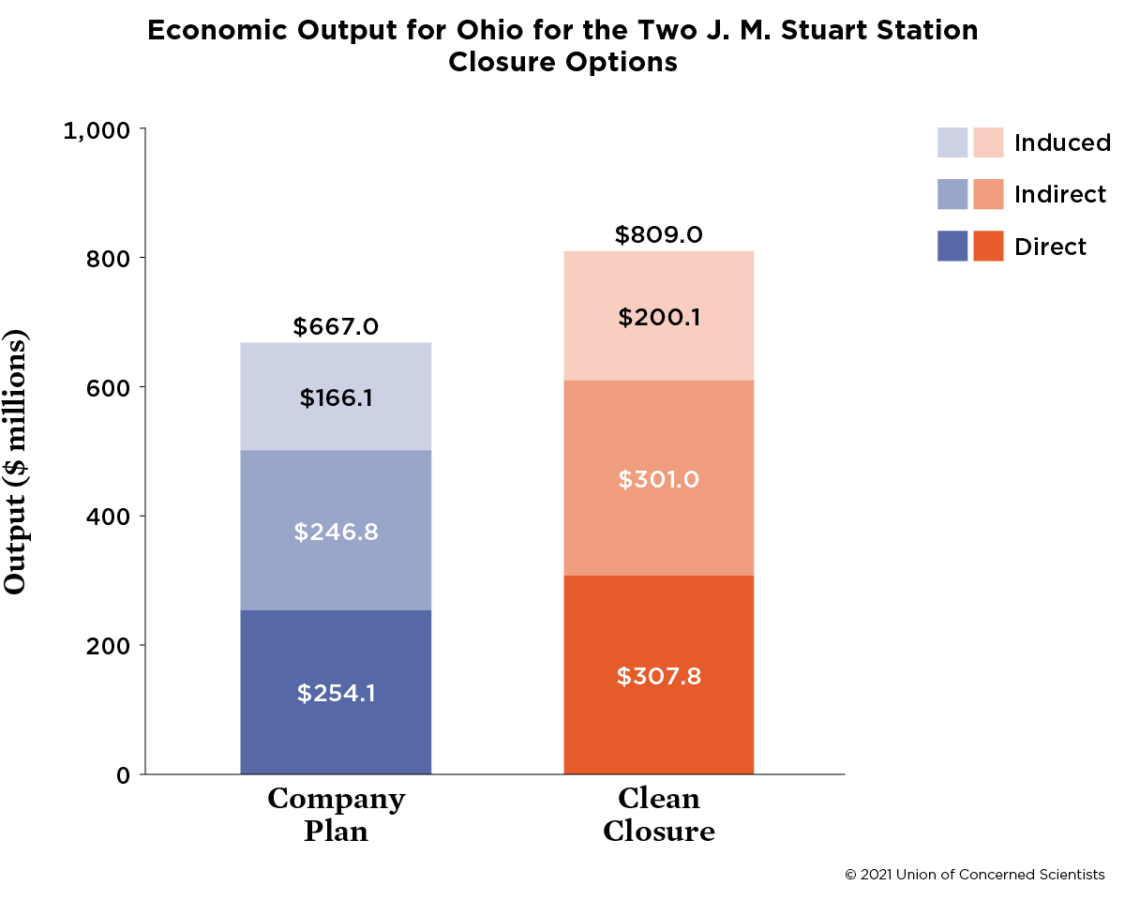

The clean closure scenario would also have considerably more impact on the local economy and job growth at the J.M. Stuart site. We estimate that the owner’s plan for construction would cost $224 million over nine years, while our clean closure plan would cost $279 million. As shown in the figures below, however, during the nine-year construction phase, our closure plan would create an estimated 314 jobs per year, while the owner’s plan would only create 252 jobs per year. The clean closure plan also would lead to $809 million in additional economic output in the state over 39 years (nine years of construction plus 30 years of monitoring), significantly more than the $667 million the owner’s plan would generate.

What to do

Fortunately, there are things that federal and state policymakers can do to ensure clean closure.

- First and foremost, the Biden administration must strictly enforce existing regulations that prohibit cap-in-place closure. The EPA’s 2015 Coal Combustion Residuals Rule already requires excavation when coal ash is in contact with groundwater if left in place. Congress should approve additional funding for EPA enforcement actions and for grants that empower fenceline communities to participate in discussions about closure options.

- Regulators must hold utilities and site owners accountable for comprehensive cleanup. Environmental regulators and utility commissions often have authority to ensure that coal ash sites are fully remediated.

- Ensure strong labor standards and safety protections for cleanup workers and prioritize dislocated workers in hiring. States should implement local hiring requirements to ensure that dislocated workers have priority access to cleanup jobs and require coal ash owners to pay prevailing wages to ensure that workers are paid fairly for their work. Most important, site owners responsible for cleanup must protect workers during operations because coal ash is extremely toxic.

(See the report for the full list of recommendations.)

Why comprehensive cleanup is essential

When coal plants close, nearby communities face fallout from lost jobs, lost local tax revenue, and an economic downturn. Many of these communities, which are disproportionately low-income or communities of color—or both, have suffered from the health impacts of coal-fired electricity generation for decades. When utilities do not sufficiently and safely clean up their coal ash sites, these communities continue to bear ongoing costs—lower property values, persistent water pollution, and the risk of catastrophic failures of inadequate containment structures—and receive no economic benefits. Remediating coal ash ponds and landfills is an essential component of any fair transition to a clean energy economy.

Ensuring that the disposal of coal ash is complete and as safe as possible would not only protect public health and the environment but would also create jobs in the very places where jobs are becoming scarce as coal mines and plants continue to close. Comprehensive cleanup would boost property values, eliminate pollution, and help communities diversify their economies, enabling them to attract new industries that will not inherit the cleanup liability, and make these communities places where more people want to live and work.