The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) is the most important diplomatic effort to reduce the risk of nuclear war, prevent the spread of nuclear weapons, and achieve complete nuclear disarmament. Last month, its latest review conference ended in frustration and failure after Russia blocked consensus on a final outcome document – but that’s only part of the story.

Why is the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty so important?

The NPT was negotiated after the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 highlighted the existential dangers of nuclear war. The NPT is often called a “grand bargain” between the non-nuclear states and the five states recognized in the Treaty as nuclear-weapons states (these were all five states that possessed nuclear weapons at the time that the treaty was written). Non-nuclear states forswear any development or possession of nuclear weapons and verify that commitment through safeguards measures. In exchange they receive access to peaceful nuclear technologies and a commitment from the nuclear states that they will pursue nuclear disarmament in “good faith.”

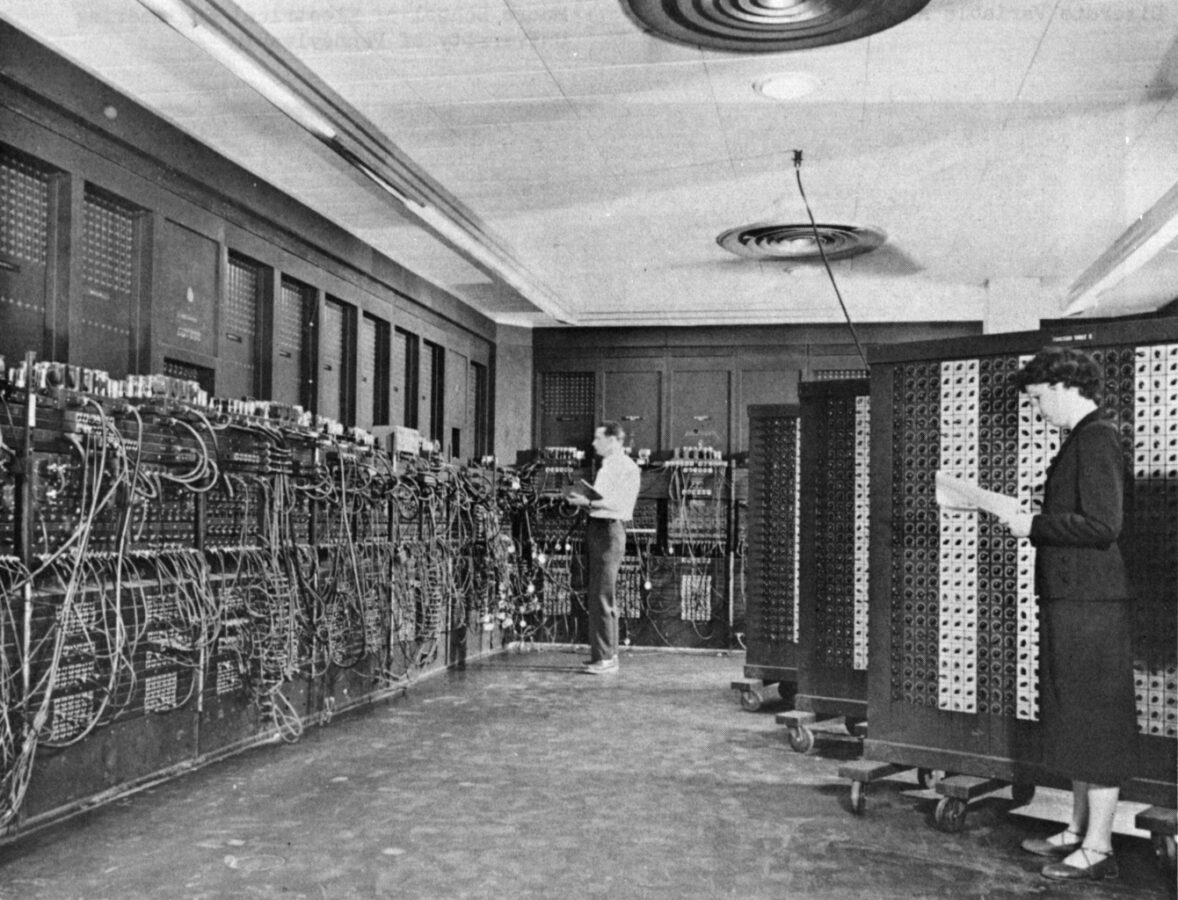

Though some still regard nuclear weapons as symbols of technical or military prestige, it is important to remember that, fundamentally, nuclear weapons are an old technology. ENIAC, the first programmable, electric digital computer, was completed at the same time as the Manhattan project. In the early years of the Cold War, it seemed inevitable that nuclear weapons would spread around the world, just like digital computing or any other technological innovation.

US Army / Wikimedia

In 1963, US President Kennedy said that he was “haunted by the feeling that by 1970 … there may be 10 nuclear powers instead of four, and by 1975, 15 or 20.” Despite several early attempts to control the spread of nuclear technologies, including the Atoms for Peace program, it was clear in Kennedy’s time that dozens of states either had ongoing nuclear weapons programs or were actively considering them.

Fortunately, Kennedy’s grim forecast was not fulfilled. Today only nine states possess nuclear weapons. Every country in the world is a member of the NPT excerpt five (India, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan and South Sudan). Most other states had quietly ended their nuclear weapons programs by the 1970s. The overwhelming majority of countries have decided against pursuing their own nuclear weapons capabilities, not because the technology is unreachable but because it is dangerous and undesirable. The world we live in, which was almost unimaginable at the beginning of the nuclear age, is thanks in large part to the NPT.

The NPT was extended indefinitely in 1995, but every five years, the members of the NPT hold a review conference to evaluate the health of the treaty and identify further actions to advance the treaty’s aims of nuclear nonproliferation and disarmament. The conference itself is a critical forum for the international community to convene regularly to work on these issues. Further, it provides an opportunity for states to issue a consensus statement in which NPT members express their collective values, identify concerns, and commit to action.

New wounds vs. chronic illness

The Tenth NPT Review Conference, initially scheduled for 2020 but delayed because of the pandemic, was finally held August 1-26, 2022. The two-year delay affected not only the timing but also the outcome of the conference; Russia’s war against Ukraine hung like a thunderstorm over the conference proceedings. Ultimately, Russia was the only state that voted against the adoption of a final document, objecting to language that acknowledged the radiological risk of military actions around Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant, which is currently occupied by Russian forces.

There is no question that Russia’s actions in the last year undermined the Tenth Review Conference. Worse, by using the threat of nuclear war to shield its aggression against a non-nuclear state, Russia has shaken norms that underpin the entire nuclear non-proliferation regime.

Yet the acute crisis of Russia’s war in Ukraine should not overshadow the chronic weaknesses of the NPT. The draft outcome document contained no innovation, no commitments, and no concrete actions towards nuclear disarmament – these had all been stripped away by the five nuclear powers and their allies, not just Russia, during the drafting process. A statement by 65 non-nuclear state parties expressed their frustration and disappointment with the final document as an effort that “[fell] dramatically short of advancing nuclear disarmament… or even concretely addressing the serious risks inherent in nuclear weapons.”

Would the draft outcome document have been better than nothing? Yes – but not by much. While undeniably harmful, Russia’s obstructionism became a convenient distraction for the other nuclear powers, one that allowed them to deflect from a second, unspoken consensus: not one step forward on nuclear disarmament.

Failure is not new at NPT review conferences, but now we are at risk of failure becoming a habit. In 2010, NPT members adopted an action plan for the first time, a major milestone. But five years later, the Ninth Review Conference fell apart over the failure of states to fulfill those commitments. Divisions between the “haves” – the five nuclear powers – and the “have-nots” – the non-nuclear states, have intensified over the last decade. More attention has also been directed to the “need-nots” – states, like those in NATO, which do not have their own nuclear weapons, but who nevertheless center nuclear weapons within their national security strategies.

As nuclear powers double down on expanding and modernizing their nuclear arsenals, the credibility and the relevance of the NPT will continue to fade. These states – and US allies – must realize that the NPT is not the foundation of the global nonproliferation regime: it is the heart. Unless it is active, it will die.

The nuclear powers cannot expect to continue enjoying the benefits of nuclear nonproliferation if they are unwilling to fulfill their own obligations to pursue nuclear disarmament. US President Kennedy once described his fear of a world with 20 nuclear powers. That world is still possible. A world without nuclear weapons is also possible, but only if we pursue it with courage and conviction.