A new study about declining aquifers in the Great Plains focuses on the agricultural sector’s water use, as it should. But water-smart power choices can help, too, by cutting electric-sector pressure on precious groundwater resources.

The study, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, looked at the status and future of the High Plains Aquifer that lies under portions of eight Great Plains states, given its big role in supplying water for irrigation. As one story put it:

Across the high plains, many farmers depend on underground stores of water, and they worry about wells going dry. A new scientific study of western Kansas lays out a predicted timeline for those fears to become reality. But it also shows an alternative path for farming in Kansas: The moment of reckoning can be delayed, and the impact softened, if farmers start conserving water now.

The power plant-aquifer nexus

The PNAS study got me thinking about power plant cooling water needs, and how they figure in to discussions about groundwater use.

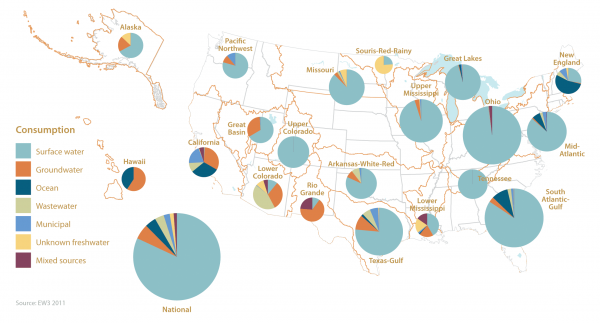

When it comes to power plants’ cooling water needs, aquifers are only one of the sources that get drawn on. The analysis we presented in our 2011 report, Freshwater Use By U.S. Power Plants, showed, not surprisingly, that lakes, rivers, and oceans accounted for almost all power plant withdrawals and consumption. Groundwater was the source for only around 6 percent of water consumed by power plants for cooling, and an even smaller slice of power plant water withdrawals.

But that analysis also found that groundwater is an important piece of the pie(s) in parts of the U.S. where surface water is hard to come by, such as in Texas and in the Great Basin in California/Nevada/Utah. There, groundwater supplied more than half of power plant water needs.

While turning to underground water is a potential approach to addressing a lack of surface water sources, we also pointed out problems with it, the fact that “[i]n many areas, power plant use combined with other water demands are draining aquifers at an unsustainable rate.”

Where power plants get their cooling water from (Source: Averyt et al. 2011, www.ucsusa.org/electricity-water-use)

And the flip side…

That brings up the other side of the power plant-aquifer nexus, the role plants play in groundwater use. When it comes to aquifer drawdowns, power plants and their water habits are also only a small piece of the equation, on average and in many places. In Kansas, for example, the focus of the PNAS report, power plants draw only 0.5 percent as much groundwater as farmers do for irrigation, according to the USGS.

But, as we talk about in Freshwater Use, in many places the story is different:

Power plants are major consumers of groundwater in several regions where such withdrawals have increased sharply in recent years, including the Las Vegas and Tucson areas.

We point to counties where power plants account for one-quarter to two-thirds of groundwater withdrawals.

Of course, even where they’re only a small piece of direct impact on groundwater levels, power plants are a big piece of the carbon emissions >> climate change >> hydrologic impacts equation, with its own impacts on how quickly aquifers get recharged.

What that all means is that our power choices matter in multiple ways when it comes to protecting groundwater resources.

Smart Options All Around

The great news is that states in the Great Plains, like the rest of the country, have plenty of choices when it comes to making the power sector fit better with our future.

Many of the states sitting above the High Plains aquifer that the PNAS study focused on are also out in front when it comes to one water-smart power option, wind. Those include South Dakota, which got 23.9 percent of its electricity from wind in 2012, Kansas (11.4%), Colorado (11.3%), and Oklahoma (10.5%). And Texas alone has a fifth of the country’s installed wind capacity.

But, our more recent research found, there are lots of opportunities for improvement, to cut the power sector’s use of water — from groundwater or surface water sources — in the near term (see chart).

Water-smart power choices could mean steep drops in power plant water consumption across the High Plains region. Every bit helps. (Source: Rogers et al. 2013, www.ucsusa.org/watersmartpower)

“Future sustainability and livability”

As the quote at the beginning of this blogpost suggests, the new Kansas study, like our Freshwater Use and new Water-Smart Power reports, is about water and choices — helping people understand the consequences of the paths we’re on and our options for improving outcomes.

When it comes to water resources, groundwater is special: a potential, valuable resource for generations to come, but one that can be jeopardized by unsustainable use. Ensuring that we use groundwater wisely now and that it’s there for the future is all the more essential in a climate change world. Whether you’re focused on agriculture, electricity, water, or other dimensions, keeping climate change manageable by aggressively cutting carbon just makes sense.

The conclusion of the Kansas study could just as easily apply to power plant choices:

Society has an opportunity now to make changes with tremendous implications for future sustainability and livability. The time to act will soon be past.

Hear, hear.