The 2021 hurricane season just started, and it’s predicted to be an active one. My colleague Dr Adrienne Hollis just wrote about the major risks to the population in hurricane-vulnerable Gulf Coast counties. In addition to existing threats from winds, extreme precipitation, flooding, and storm surges, people in the Gulf Coast are now facing an incomplete and inequitable COVID syndemic recovery, where unemployment and poverty are very high and large majorities of vaccine-eligible people have not yet received it, placing them at risk of COVID contagion in case of hurricane evacuations that can put people in close contact with each other.

But how is Puerto Rico faring? Puerto Rico is one among a few other unincorporated US island territories with climate, environmental, and socio-economic risks, that overlap those in the lower 48 states. Unincorporated island territories also face some unique vulnerabilities due to their geography and also because of lack of governance and political rights, and in the case of Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands, an incomplete recovery following the disastrous 2017 hurricane season.

Food insecurity in Puerto Rico has increased since the pandemic began

About 43.5% of Puerto Ricans and 57% of children in Puerto Rico lived in poverty in 2018. Since the start of the pandemic, it is estimated that 40% of Puerto Rican families experience food insecurity, an increase from about 30% reported in 2019. At the start of the pandemic, the previous administration distributed food to families in Puerto Rico under the USDA’s Farmers to Families Food Box Program. The Biden administration ended the program at the end of May citing improvements in the US economy since the start of the year, and expects to continue assisting hungry families through increased spending in federal programs like the Puerto Rico-specific Programa de Asistencia Nutricional (Nutrition Assistance Program, NAP, not the same as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program in the states) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). Unlike SNAP, however, NAP has a funding cap that does not meet the needs of Puerto Ricans who experience high rates of poverty. The Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA), which provided payments to many who were not otherwise eligible for unemployment benefits, was a temporary relief measure enacted by the CARES ACt, but that ended at the end of 2020. With high unemployment (see below) and a steady increase in the Consumer Price Index in Puerto Rico, many more families will continue to chronically experience food insecurity.

Recently I had a chance to talk to Sara López, foundress and Executive Director of Puerto Rico Rises, a non-profit that started in the US Puerto Rican diaspora and that delivers aid to Puerto Ricans in need in the island (to be fully transparent, I served as president of Puerto Rico Rises’ board for three years since its foundation, and I remain a volunteer). She had some good insights on the ground in Puerto Rico about the hunger situation:

I have spoken to [other] community leaders and unemployment is rampant. Many relied too much on the PUA (Pandemic Unemployment Assistance) payouts and now that those have ended, things have become difficult…high prices on everything…it’s disconcerting to look at supermarket shopping flyers because prices are highly inflated. People did not get ready, did not save, have not done prevention. Unemployment assistance and [USDA] food boxes were taken for granted. There was no guidance or planning for when those programs ended, and now the noose has tightened…It’s almost as if the population had been picked up and then dropped without a plan B. And there’s hunger…money is tight and at least the food box represented a savings of 30-40 dollars per week.

-Sara López, Puerto Rico Rises

Health care

An aging population, economic instability, and weakening of the public health infrastructure have plagued Puerto Rico for years. The Urban Institute reported in 2017 that health care payments in both private and public sectors depend heavily on Medicare and Medicaid, but Medicaid in Puerto Rico has federal funding caps and reduced beneficiary payments compared to the rest of the states. Mass migration of physicians and nurses to the US has led to a shortage of specialists.

There are many other problems that point to the degradation of the health care infrastructure. For example, the island town of Vieques (population approximately 9,000 – it’s the largest of the two islands off the Puerto Rican east coast) does not have a hospital since Hurricane María destroyed it in 2017. The lack of a hospital was blamed in part for the recent death of a small child while awaiting medical transport to the main island.

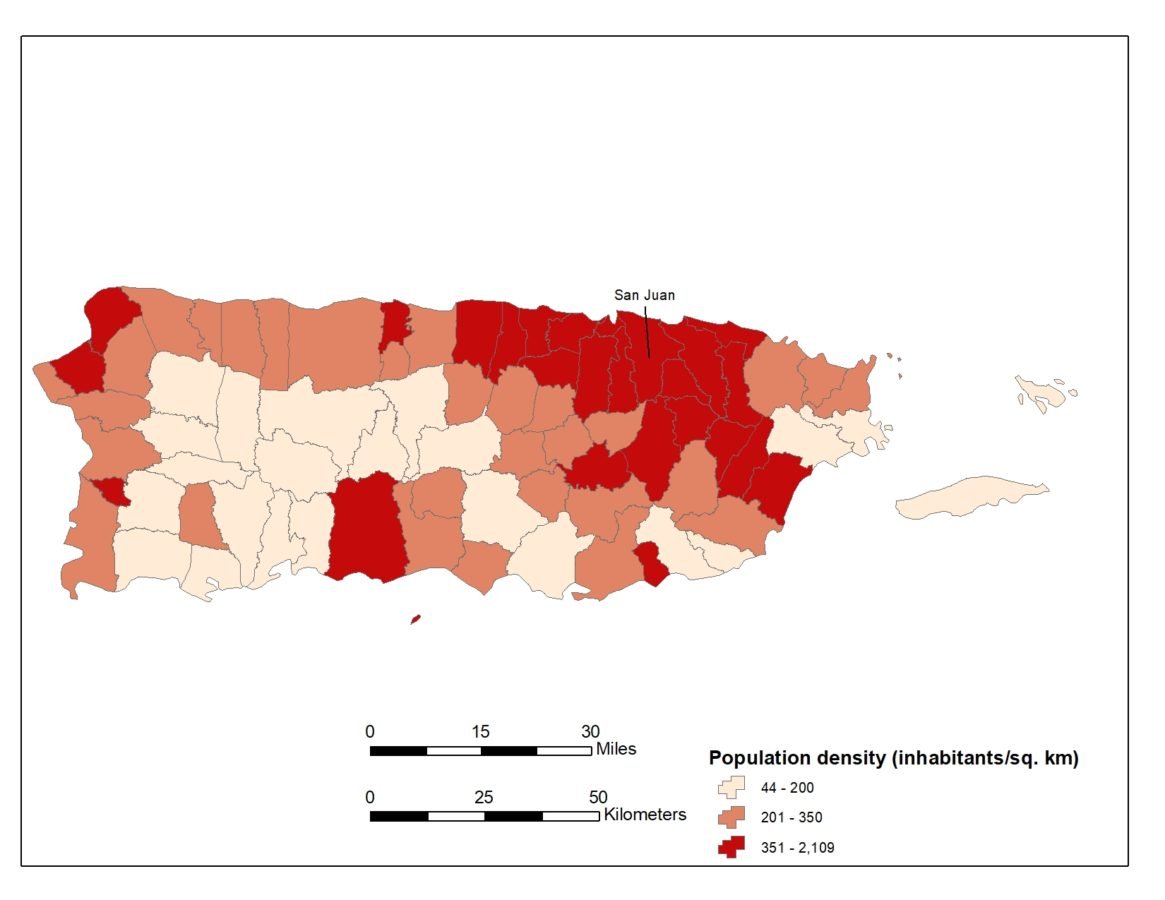

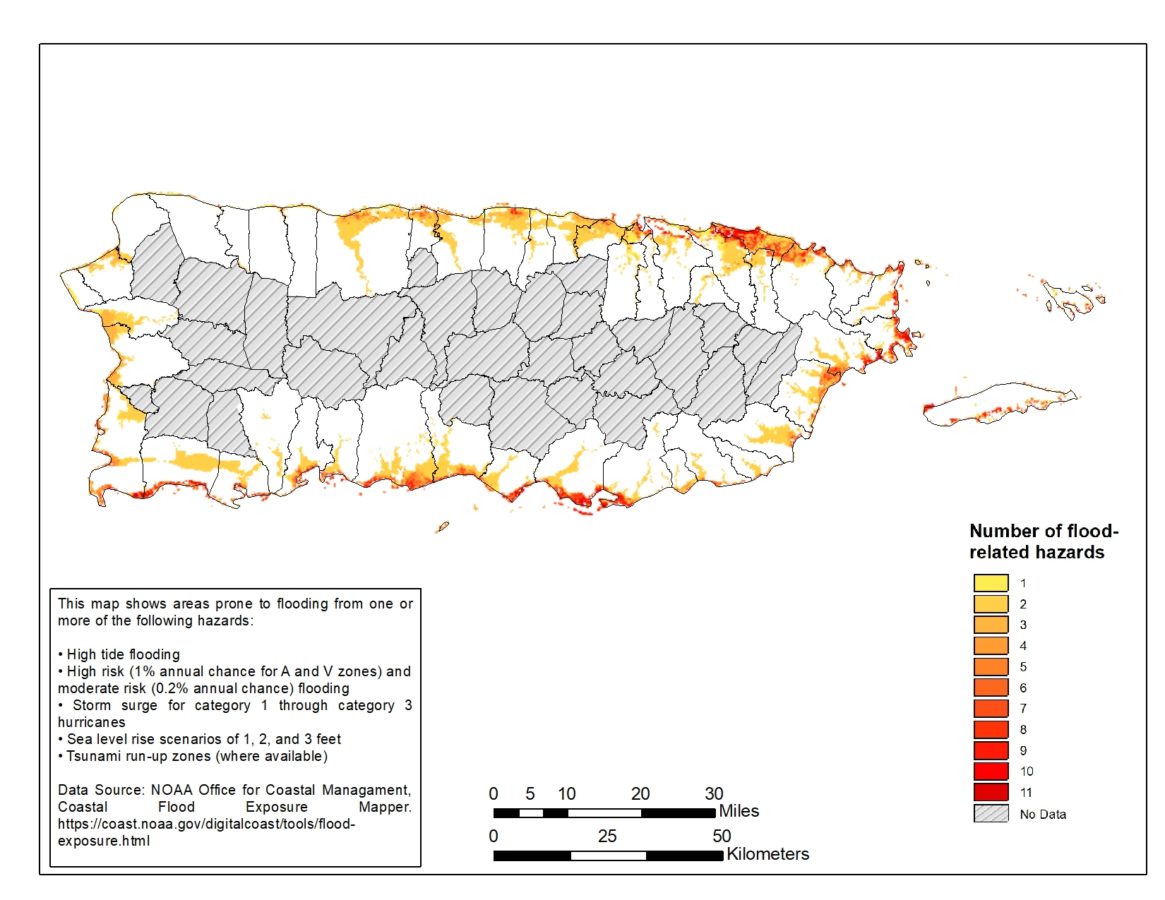

Densely-populated areas are facing multiple flood-related coastal hazards

Puerto Rico has a high population density – roughly 1,000 persons per square mile (about 350 per square kilometer), and it’s generally higher in the northern coastal plain and near San Juan. Many of these coastal areas are facing multiple, simultaneous hazards that increase flooding risks, including 100- and 500-year floods, storm surge from Category 1 through Category 3 hurricanes, sea level rise, and even tsunami risks.

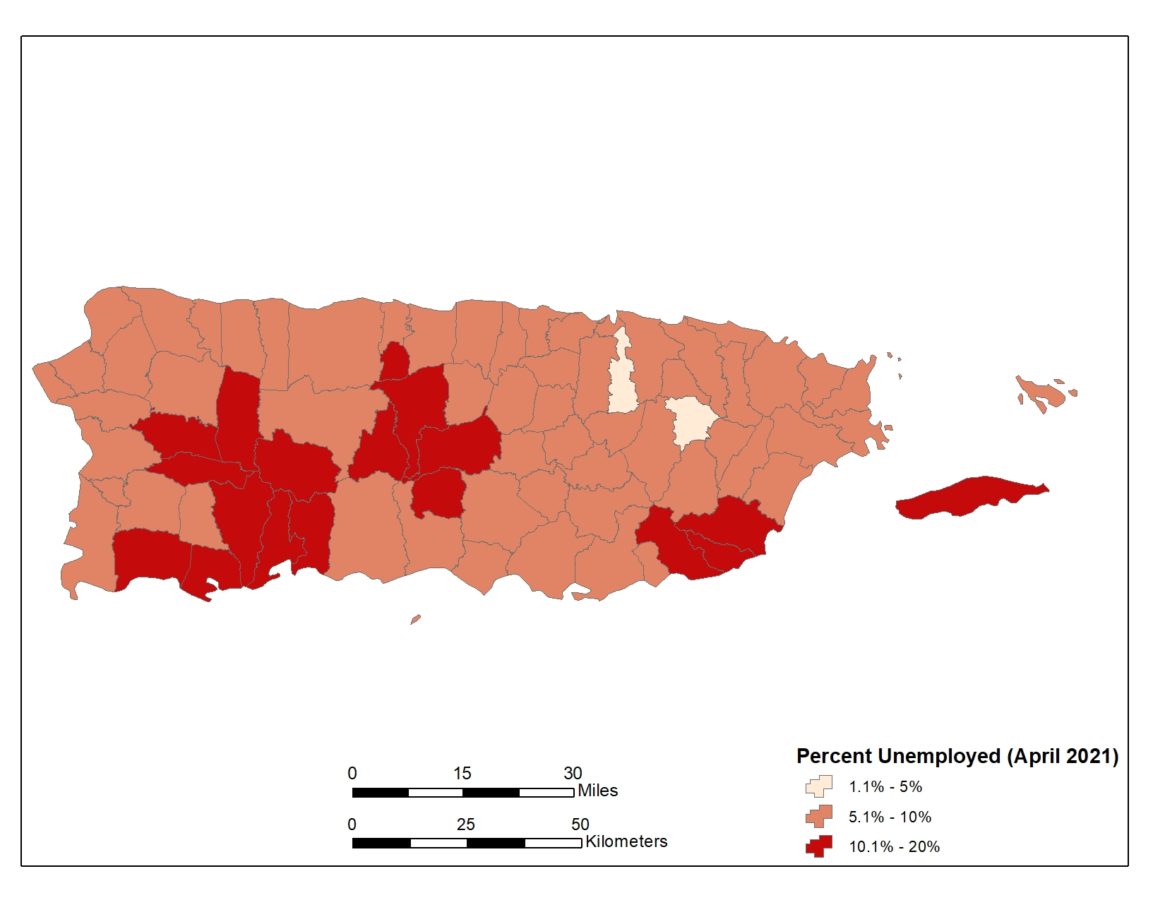

Unemployment remains high in Puerto Rico

The overall unemployment rate in Puerto Rico in April 2021 was 8.4 percent, and since May 2020 has ranged between 8.3 – 9.3 percent of the labor force. In most municipios it has remained at or below 10 percent, but in many interior mountain areas it is a whopping 10-20 percent.

The power company just switched to private hands, and there are many concerns about its reliability and resilience when a hurricane hits

Just in time for the start of the hurricane season, operations other than power generation of the public Autoridad de Energía Eléctrica (Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority, PREPA) have been privatized in a transfer to LUMA Energy, a US-Canada consortium. The terms of the contract that formalized the privatization raise numerous concerns about LUMA’s ability to operate the power grid reliably, safely, and economically. Since the contract does not provide for the transfer of current PREPA workers to LUMA, in early May the company made job offers to about 900 PREPA workers out of the 3,800 who work in transmission, distribution, and administration. That means that as the hurricane season starts, the electrical system does not have the skilled and experienced personnel that will be critical to keep the lights on when hurricanes, storm surge, and flooding threaten the system. Inexplicably, a clause in the contract allows LUMA to cancel the contract if a major disaster prevents operations for a period of 18 months. Finally, the contract requires the Puerto Rican government to finance the privatization by taking out a loan for $894 million to fund the agreement. This is a clear signal that LUMA does not have the means to acquire PREPA’s assets, and it’s hard to understand why the Puerto Rican people should foot the bill for a private company to enter the archipelago’s market.

There’s good news though – diminishing COVID cases, vaccination rates are increasing, and a White House sympathetic to the plight of Puerto Ricans

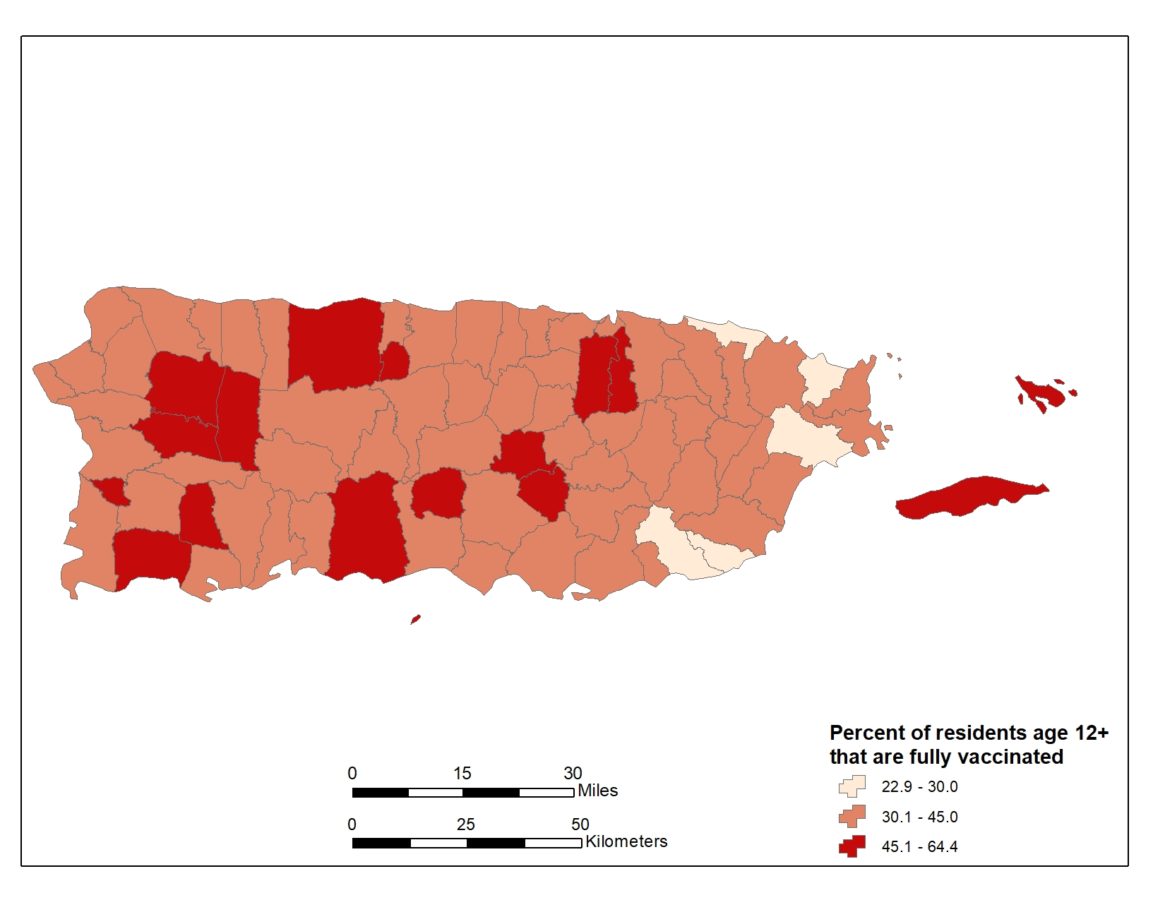

As of June 2, 2021, a little over half of Puerto Rico’s population (51.1%) had received at least one dose of the COVID vaccine (matching the US overall rate), and the rate is steadily increasing. This is in stark contrast with many southern states such as Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Georgia where only about one-third of the population of each of those states had received at least one dose.

A strict nightly curfew in effect since March of last year and prioritizing vaccinations earlier this year to persons 60 or older, or with chronic conditions or immunocompromised are some of the measures credited to contributing to a steady drop in cases since mid/late April 2021.

Also, at the federal level there are promising developments that contrast with the scorn with which the previous administration treated my people. President Biden recently lifted Department of Housing and recovery fund restrictions that the previous administration created for Puerto Rico and prevented disbursement for three years after Congress appropriated the funds. President Biden’s proposed budget includes elimination of the Medicaid funding cap and also parity in beneficiary payments for the island. The proposed Insular Areas Climate Change bill in the US House of Representatives seeks the creation of federal programs and mechanisms to strengthen all US territories’ capacity to respond to climate impacts.

The Center for American Progress has outlined a series of executive actions that President Biden can take to aid Puerto Rico, including waiving of the Jones Act, extending relief to the island towns of Vieques and Culebra, and boosting federal support for agriculture, among others. On the congressional side, reducing Puerto Rico’s gargantuan 72-billion dollar debt (which is slated to go up by 894 million dollars as part of the LUMA contract!), and reducing the absolute powers of the Fiscal Oversight Management Board (FOMB) that have directed and approved changes to Puerto Rico’s economy and finances that prioritize bondholders and private corporations, and drafting an immediate aid package for the territory are some of the measures that Congress should take now.

These are steps in the right direction to redress the callousness of the previous administration towards the people of Puerto Rico, but Puerto Rico’s problems are structural and rooted in the lack of governance and political rights from its 123-year old colonial relationship with the United States. The Puerto Rico Self-Determination Act seeks to redress this by creating a process for decolonization that binds Congress to act on the will of the Puerto Rican people regarding their political status.

An active hurricane season, coastal hazards, high unemployment, battered energy and public health infrastructures, disparities in federal funding, lack of political rights, and COVID will mean more suffering for Puerto Ricans when the next storm threatens the island.