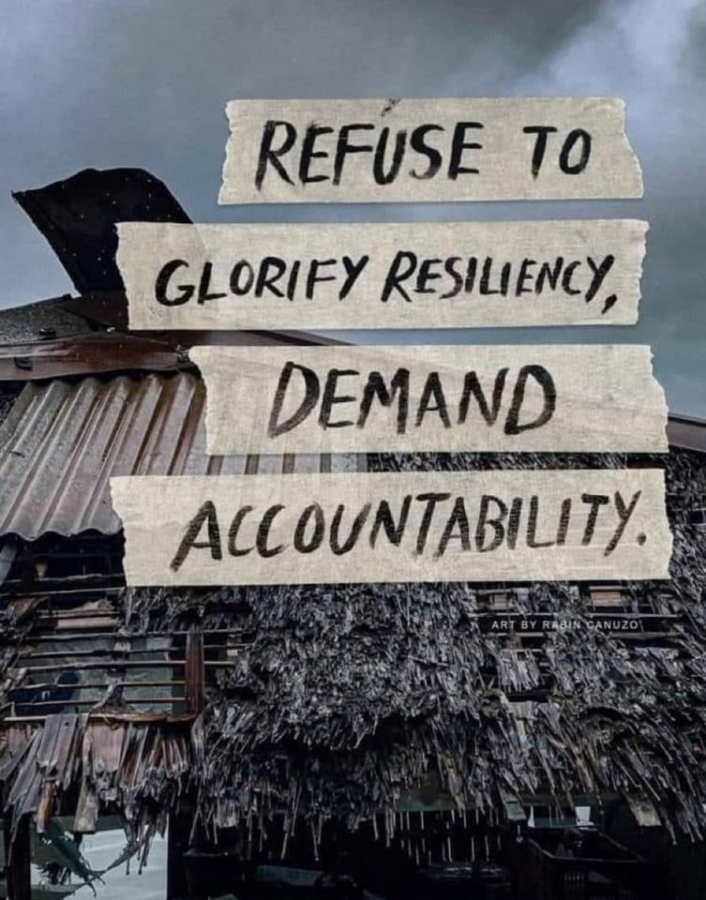

“Refuse to glorify resilience; demand accountability.” Thus reads a meme on Puerto Rican social media, the background image a house with a wind-battered roof, a combination of rusted tin and ragged palm tree leaves. It is illustrative of the growing discontent of Puerto Ricans at being called resilient in the face of Hurricanes Maria and Fiona. But wait…aren’t Puerto Ricans resilient to the torrential rains, flooding, and winds that hurricane season brings year after year? Aren’t they (shouldn’t they!) be used to, adapted to, resilient to, the undeniable climate and extreme weather realities that are part of living in the Caribbean? Before answering the question, let’s unpack these assumptions first.

The idea that populations facing climate and other social, economic, or environmental disasters are innately resilient to climate and other environmental impacts is long-standing and incorrect. It is a harmful framing that romanticizes the conditions of duress under which impacted populations attempt to survive disasters when they already live, day in, day out, in precarious circumstances. It is also a convenient framing that leaves governments off the hook and unaccountable for their own unwillingness to prioritize the wellbeing of vulnerable populations and adequately respond to risks to which scientists have provided plenty of warning and solutions.

And the etymology of resilience contributes to the problem as well. It evokes elasticity—of a rubber band or a NERF ball, for example—that allows something that becomes deformed or bent out of shape by an external force to return to its original form or condition. But people and the social, technological, economic, and political systems upon which they rely to live their lives are not rubber bands or foam balls. Even if people and the things they require had such elasticity, in the face of climate upheavals spiraling out of control, it is not desirable to return to the original form.

What is desirable and needed is to reshape into a form that can prevent or minimize the deformation in the first place, especially when the strength of the force is increasing under a changing climate. Case in point: Hurricanes are increasing in frequency and severity due to climate change, and climate change can also cause them to rapidly intensify and slow down as they approach land, releasing more rain. To be fair, the concept of resilience has evolved to recognize that achieving resilience means augmenting or creating the capacity of people and the infrastructure they rely upon to withstand not only current, but projected and very likely unavoidable climate impacts even with rapid emissions reductions.

But the consequences of framing resiliency as innate to certain populations are unfolding right now in the insufficient response to the crisis after Hurricane Fiona in Puerto Rico, which has worsened due to the terrible decisions that were made in the five years since Hurricane Maria.

For the US federal and Puerto Rico governments, this convenient narrative of Puerto Rican resilience rests on the supposition that the population can and will put up with any and all impositions and humiliations that are enabled by the fact that Puerto Rico remains a colony of the US: the austerity in social services dictated by the federally-appointed Fiscal Oversight Management Board, continued failings by power company LUMA, and the dismantlement of UTIER—the union covering those working at Puerto Rico’s electric power authority PREPA—are but a few recent examples.

But that is flat wrong. Puerto Ricans are demanding that the federal and local governments provide the resources and infrastructure to build the resilience needed for thriving in a warmer world as well as take action to limit how bad climate change will get. Puerto Ricans don’t want their suffering to be cast aside and romanticized as resilient; they demand an adequate recovery.

And achieving an equitable and resilient recovery depends in turn on practices that are abundant among the Puerto Rican people: solidarity, generosity, empathy (as the political comedian and commentator Silverio Pérez recently wrote). Just turn to social media to look at the network of Centros de Apoyo Mutuo (Mutual Aid Centers) and other collectives that are pooling resources to provide food, power, coffee, kitchens, even a solar-powered community movie theater, to Puerto Ricans in need.

This takes me back to the effect of labeling impoverished, marginalized populations resilient, as if resiliency were an essential characteristic that defines them. To restore, to rebuild in order to withstand current and future climate impacts requires, in the words of food systems and global health expert Dr. Abrania Marrero, that we “recognize that [Puerto Rican] individuals and communities, in their collective power, are not helpless victims.” It also requires admitting that “’resilience’ was a word reserved for populations marginalized by centuries of disinvestment and manipulation—which distracts us from making the changes needed to never experience disaster again.”

And it is precisely both long-standing marginalization and disinvestment that have created the conditions that make Puerto Ricans so vulnerable to climate change. Precariousness and vulnerability to climate change—let’s call it lack of resilience to stay on topic—have worsened gradually in Puerto Rico and left the territory without adequate resources to handle Maria and now Fiona.

Historically, the US government has treated Puerto Ricans as ignorant and unfit to make decisions that affect their lives (this very offensive and racist newspaper cartoon from more than a century ago is a reminder of how the people of the US territories have been regarded).

So, no. Puerto Ricans are not inherently resilient. Some are surviving on the island, some have fled (more aggravatingly and unwittingly, towards the misery that Hurricane Ian is projected to bring to Florida); thousands died in the Hurricane Maria aftermath.

What they are is fed up with an incompetent and callous Puerto Rican government that continuously fails to heed the expertise of climate, renewable energy, infrastructure, and community experts, instead being obsessed only with the optics of how their narrow partisan goals are perceived in Washington, DC. They are fed up with a federally imposed colonial junta that has dictated nothing but austerity in order to pay Wall Street. They are fed up with LUMA, an absurd energy grid privatization deal that can’t keep the lights on and creates even larger fiscal and energy burdens for Puerto Ricans. They are fed up with the increasing unaffordability of homes enabled by tax haven laws adopted by the Puerto Rican government. So, don’t call our people resilient, because Puerto Ricans will not be resilient until that resilience is built and until:

- A distributed, modular, affordable energy grid is built according to demonstrated renewable energy practices that are also mandated by Puerto Rican law;

- The LUMA contract is canceled;

- Substantial local knowledge of Puerto Rican credentialed and community experts is incorporated in the search for solutions;

- Construction and reconstruction projects, including homes, comply with existing environmental protections and are built to climate-informed flood standards;

- The anti-democratic Fiscal Oversight Management Board ends its reign of austerity;

- The Jones Act no longer stands as an impediment to importing consumer goods and other prime materials;

- Tax havens created by Puerto Rico’s Act 20 and Act 22 stop enabling a massive land grab and gentrification of prime coastal and interior real estate by disaster capitalist investors;

- PREPA is adequately funded and managed to once again be a public entity that serves the energy needs of the people of Puerto Rico;

- The thousands of experienced, former PREPA workers are allowed to return to serve Puerto Rico enjoying the benefits of the workers’ union UTIER,

Until these things happen and Puerto Rico is on its way to a just and equitable recovery, our people won’t become resilient. I have one final thought in the words of Don’t Call Me Resilient podcast host Vinita Srivastava: “Instead of calling people resilient, let’s instead look at solutions for those things we should not have to be resilient for.”