In April 2021, President Biden committed the United States to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions 50 to 52 percent below 2005 levels by 2030, in line with science-informed targets, in line with the collective hunt to keep global warming below 2 degrees C, in line with the fight, the fight, the global fight to beat back the worst of climate impacts we could see.

Ever since, the scramble has been on for our nation to advance the charge.

Because while President Biden’s commitment to robust climate action is critical to setting the forward course, words alone will not guarantee progress. Wish as we might, we will not whoopsie-pie our way into the Great Decarbonized Place.

We need actual action.

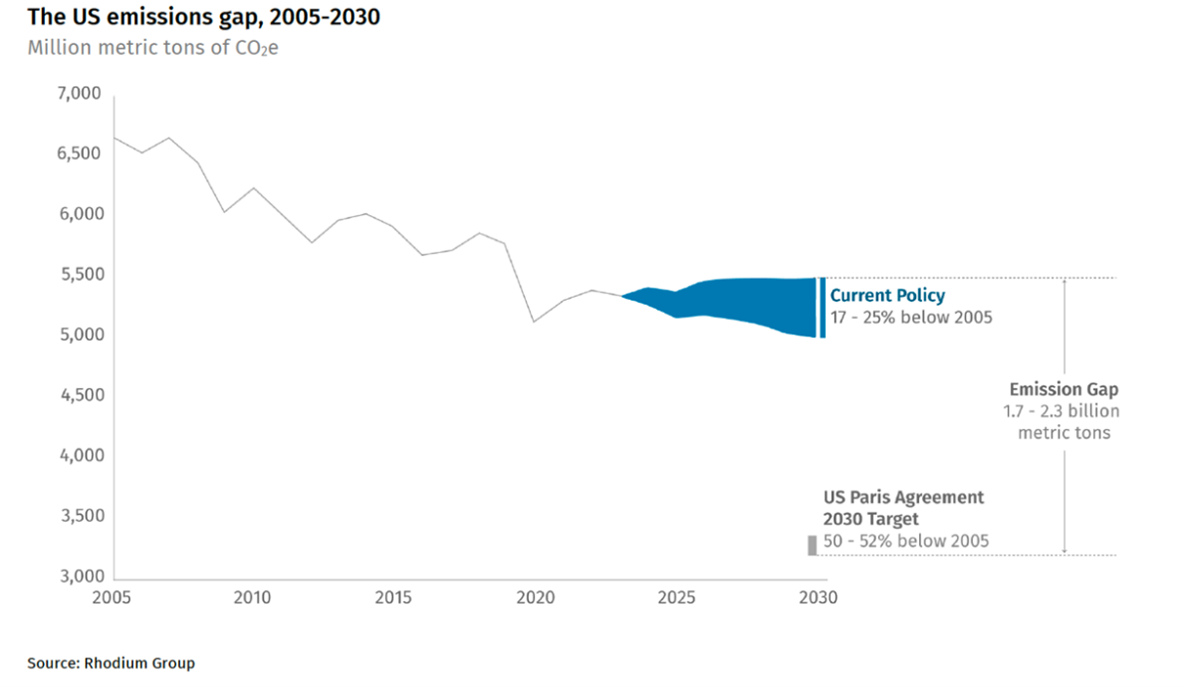

We need actual policy, actual progress, actual change, commensurate with the level of action these climate targets require. And they will require a lot, as new modeling makes clear:

Precisely because the present emissions gap is so great, we cannot solely lean on the incredible progress enabled by leading states, localities, businesses, and individuals. To truly bend the curve, we need federal action, too.

And that is what makes the repeated and escalating broadsides to the climate integrity of the Build Back Better Act—foremost among them attacks on the Clean Electricity Performance Program (CEPP)—so infuriating.

Because no matter what words are spun, what justifications are launched, we will still need to make up the gap. So for every measure of weakening Congress allows, for every degree of ambition our lawmakers abandon, it will simply make the hard task harder, placing a heavier burden on all the other efforts we need to make.

The Build Back Better Act as a chance for change

There was never going to be one legislative package to resolve the path to 2030 and beyond—not least because action will be required across all facets of government, not just Congress. But the Build Back Better Act (also referred to as the budget reconciliation package) was set up to advance climate action—along with so much else—at a level of ambition not previously seen, finally showing Congress going beyond its long-favored realm of tinkering at the edges to enact climate policies that would actually drive path-shifting, curve-bending change.

This is the type of ambition we’ve been waiting for; this is the type of ambition we need.

And this is the type of ambition that fossil fuel interests cannot abide.

So here we are now, staring down significant and multifaceted attacks to the very heart of that ambition, primarily through threats to the CEPP—which would spur the power sector to swiftly transition to clean sources—but also from additional threats to broader programmatic budgets and ambitions.

While compromise is par for the course, legislators cannot capitulate when it comes to including policies that enable major change. So for every cut, for every slash, they must answer: If not this, then what? Because we need major change.

Meeting 2030 targets hinges on power sector transition

To get climate action on track, emissions reductions will need to be drawn from all parts of the economy, all the way from cars on the road to buildings and homes. The Build Back Better Act includes multiple major policies to advance these efforts.

But for the race to 2030 targets, foremost among all the rest is achieving swift, deep reductions from the nation’s electric power sector. This is the foundation upon which so much else of our climate progress will be built, because the end goal for much of what runs on fossil fuels in our economy today is for it to run on electricity tomorrow—and that electricity must be clean.

We need policy interventions to support that.

Because while the nation’s power sector has been undergoing a significant transition away from heavily polluting coal, progress has been uneven and far too much of what has come online to fill the gaps has been still-polluting gas. The country is still hovering at 60 percent fossil fuels in its electricity mix, and coal generation is projected to increase, not decrease, this year.

To address this, policies can do two things: boost the good, and limit the bad.

We need both. We need both because while the former is vital to clean energy deployment, it studiously avoids antagonizing the fossil fuel-fired status quo, and history makes clear that fossil fuel interests will not voluntarily undertake this mission on their own.

This is the reason that the threat of the CEPP falling out of the Build Back Better Act is so significant. It’s not that there aren’t multiple additional policies that will help to spur clean electricity deployment in the bill—there are, and they are incredible, from updated and broadened tax incentives to support for transitioning fossil fuel assets—it’s that the CEPP includes targets, and the CEPP includes sticks.

Without the CEPP, renewables would still be cheap, but they might not be evenly—or sufficiently—deployed, and too many utilities are at risk of sticking too tightly to coal and gas. And that could lead to a non-trivial erosion of the emissions reduction potential of the legislation, as estimated by multiple recent analyses.

So if the CEPP falls out, what comes next?

Within the Build Back Better Act, Congress can approximate the same power sector intent from other types of programs that similarly support both sides of this transition, i.e., toward renewables and away from polluting fossil fuels. It can also look elsewhere to achieve deeper cuts in other sectors.

But it would be a heavy lift. And all the more so if other major initiatives in the Build Back Better Act fall out, from critical environmental justice initiatives to the robust clean energy tax incentives to the methane fee, which the fossil fuel industry is doing everything in its power to unwind.

And otherwise? It’s on to other actors, and a heavier burden for each.

If not this, then what?

No matter what happens with the Build Back Better Act, to reach the 2030 climate targets set by President Biden, the country will need to bring every lever to bear, from states, localities, and businesses to the federal government, Congress and the administration both, and the country will need to look to every economic sector for gains, and the country will need to sustain these efforts throughout the years to come. Any less in one area means more required by the rest.

Recent modeling by Rhodium Group supports this finding, making clear that a forward path exists even if the CEPP falls out. But it would require even more progress by leading states, and rapid action by the Environmental Protection Agency and other federal agencies across multiple sectors, from standards limiting new, unmitigated gas-fired power plants to near-term coverage of refineries and other major emitters.

Much as fossil fuel interests might wish it, undermining one major tool for climate action doesn’t make the problem go away—it just forces taking other, often more difficult, ways.

We do not have time for craven capitulation to inaction. It’s time to make the leap.