It’s almost the end of California’s wet season. California is in a Mediterranean climate zone, characterized by long, dry summers and short, wet winters. Snow is a crucial part of our year-round water supply, serving as a natural reservoir and providing up to a third of our water supply. Today, the California Department of Water Resources conducted a snow survey to determine how much snow we have stockpiled to date. Today’s survey shows we are at 85% of average levels, statewide. That could spell trouble given above average temperatures that the state is currently experiencing. In addition, significant regional differences reveal some of the ways climate change is shifting our water supplies.

| Statewide | North | Central | South | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent of normal to date | 85% | 104% | 80% | 70% |

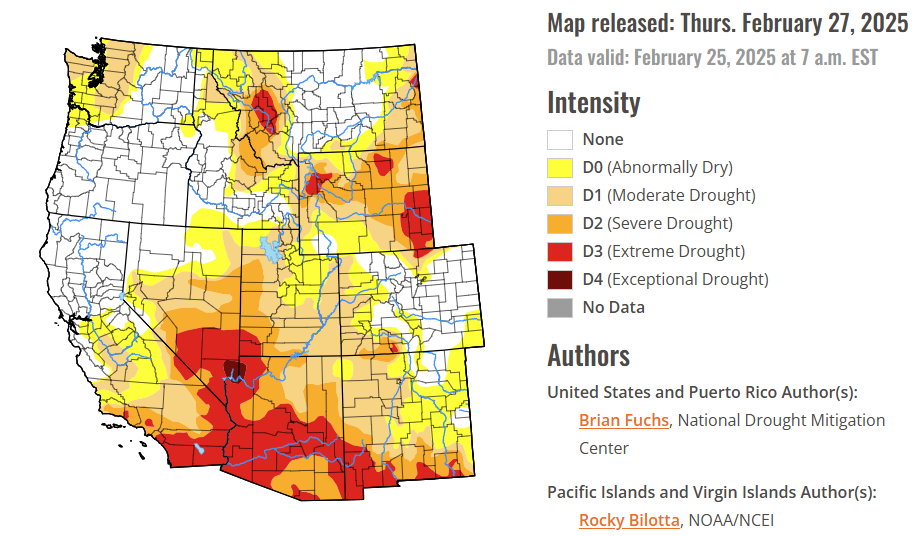

While February saw a set of strong atmospheric rivers bring snow to Northern California, Southern California is still well below average for yearly precipitation. Indeed, drought conditions are present across Southern California and much of the American West. In addition, 2024 was the world’s warmest on record globally, and the first calendar year in which global temperatures exceeded 1.5°C above its pre-industrial levels. Recent wildfires in the Los Angeles (LA) region highlighted the sometimes-disastrous consequences of this combination of hot and dry conditions. Scientists have found that climate change made the conditions that drove the devastating fires some 35 percent more likely than they would have been had the fires occurred before humans began burning fossil fuels on a large scale.

Climate change is increasing the gap between water supply and water demand

Climate change is increasing the misalignment between when we get water from our snowpack and when we need it in our streams, fields, and cities. As climate change accelerates snowmelt and heats up spring temperatures, springtime runoff is projected to peak between 25 and 50 days earlier than it does now. That’s around a month added to California’s dry season when other stored water resources will need to meet demand. The Department of Water Resources noted that current above average temperatures mean snowpack is melting quickly.

Warming temperatures also amplify the risk of the water stored in snowpack coming down in massive, damaging, and hard-to-capture flood events rather than a more gradual steady stream. This can happen when lots of rain falls on top of snowpack, washing both the rainfall and the snowmelt into streams all at once—as in Oregon’s 1996 Willamette River flood, one of the worst natural disasters in that state’s history. The state of flooding emergency called for LA in 2017 and the devastating flooding in the US Midwest in 2019 was a similar situation.

Political stunts aren’t helping

What all this means is that there is more of a need to conserve our dwindling winter water supplies for the long, dry summer season. Despite this, President Trump unexpectedly ordered the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to release water from dams into the federal water supply system known as the Central Valley Project last month. This political stunt not only did not help anyone in Southern California fight fires but also wasted water that could have been stored for the summer. The sudden water release came without local and state coordination, threatening to undermine earthen levies that protect many farms and cities in the Central Valley. No one benefited— not farmers, not fish, not cities.

The political theater didn’t stop there. A related Executive Order directed federal water projects to ignore legal protections like the endangered species act and water quality standards in order to pump more water South. Unfortunately, the reality is that exporting significantly more water out of the Delta actually threatens Southern California’s water supply. The Public Policy Institute of California explains: “If the Central Valley Project takes more water out of the Delta, the burden to meet water quality standards would fall on the State Water Project. This would likely lead to less water available for Southern California, not more.”

Currently, the federal Central Valley Project and the State Water Project share the burden of meeting state and federal water quality standards in the Bay Delta. These standards protect drinking water quality, requiring enough water to flow out through the Bay Delta and into San Francisco Bay to hold back seawater that would otherwise intrude and make the water too salty for human consumption.

Real solutions to climate-proof water supplies are available

Indeed, LA’s largest wholesale water provider, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, has shifted from an historic focus on increasing water imports to maximizing local water supplies, like water recycling, given climate impacts. That’s why the Metropolitan Water District, along with many other water agencies, supported the recent climate bond to invest in a range of smart water solutions.

These include climate-proof strategies, such as:

- increasing groundwater recharge and storage,

- modernizing water rights,

- strategically repurposing land to maximize water savings and community well-being,

- and conserving and reusing whenever possible.

Californians resoundingly support these solutions, as shown by the passage of the climate bond in November 2024. While we expect the federal political stunts to continue, states can chart their own path to real solutions. In red and blue states alike, people expect government to continue to provide essential services like safe and affordable drinking water. Now, more than ever, states must step up.