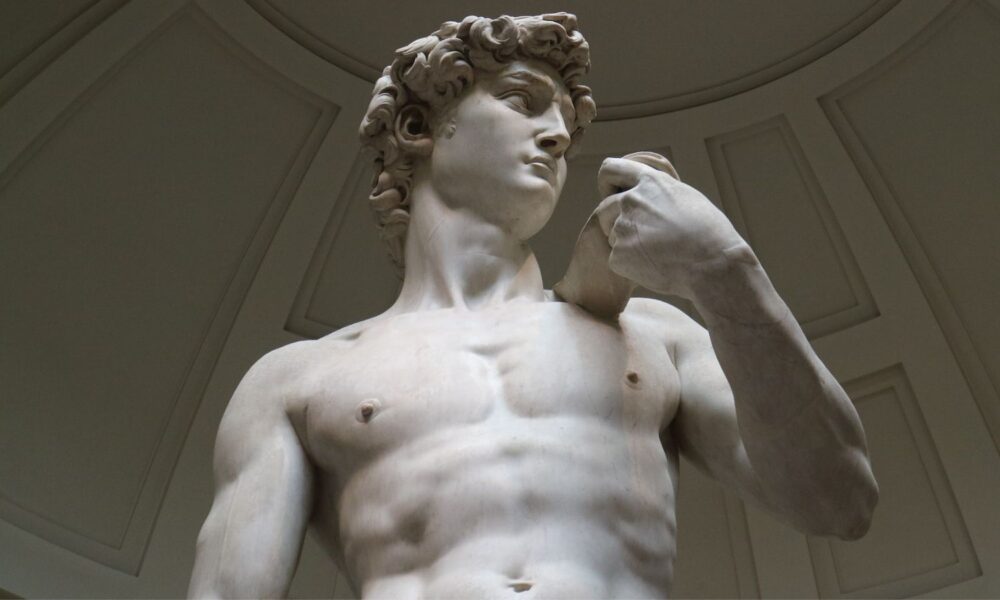

Picture the small shepherd boy, David, pitted against the enormous warrior, Goliath. This is how it can feel when I step up to the microphone in the Capitol in Sacramento, California, to discuss some science-based analysis with policy makers. There is usually a line of lobbyists waiting to dispute any and all facts I, and other scientists like me, present. These, often well-heeled, Sacramento insiders represent oil companies, irrigation districts, and water agencies. They tend to have a similar set of talking points, written well in advance of the discussion, which they read off their cell phones before ducking out to do the same at another hearing in a different room.

In such moments, it can be easy to feel overwhelmed, unheard, even helpless. Whenever I feel this way, I stop and remind myself that, sometimes, the little guy wins.

Indeed, that is the story I would like to tell you: a true tale of the trials, tribulations, and eventual triumph of the underdog.

Trials

I recently returned to the Union of Concerned Scientists as the Western States Regional Director. Previously, I was a Senior Climate Scientist, and as such I was part of an effort to address unregulated groundwater mining in California through the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (or SGMA). Back in 2014, California was the very last Western state to realize that everyone pumping as much groundwater as they could wasn’t a great long-term strategy to meet our collective water needs.

At the time, UCS was laser focused on ensuring that the act included requirements to consider climate change in the planning process. This was still considered a rather wonky and niche interest; recall this was long before the terms “atmospheric river” or “weather whiplash” were on everyone’s minds, before the youth climate strike of 2019, raging fires in Australia, the Amazon, Europe, and the Western United States, or the increasing attention on 2030 as a key year for the global community to reach its climate goals.

While we were able to successfully include climate change impacts in the bill, two major concessions were made that created significant obstacles for implementation: 1) groundwater basins were allowed to subdivide into many smaller sub-units, and 2) we lost the battle to require transparent, open-source groundwater models.

Open-source simply means that the data and assumptions used to model how groundwater works would be accessible to anyone and that you wouldn’t need to purchase special software to run the model. This was already a requirement in Texas’ groundwater law, and it seemed like a no-brainer to me. Importantly, it was one of the only ways to ensure that everyone was using the same assumptions and it was also the best way to ensure a rigorous review process that didn’t waste hundreds of hours of time trying to recreate black-box models.

In the end, the water industry and the Department of Water Resources helped strip this requirement from the bill.

Goliath won round 1.

Tribulations

Fast forward several years: groundwater agencies are formed, groundwater plans are developed, and those plans are submitted to the Department of Water Resources for review. Now, we have hundreds of plans, each comprised of hundreds of pages, and each using different models to estimate how groundwater works in their region (sometimes contradicting the models of overlapping and neighboring areas!).

What a mess!

Unfazed by the daunting project ahead, my UCS colleague, Dr. Pablo Ortiz, teamed up with others in the Groundwater Leadership Forum and got to work.

Led by Clean Water Action, this group reviewed 95 groundwater plans, combing through thousands of pages (of mostly unhelpful information) to try to find these key components: 1) the agency’s understanding of the impact of groundwater management on drinking water, 2) the incorporation of climate change scenarios in their plan, 3) an understanding of their impacts on the environment, and 4) the level of engagement of diverse stakeholders.

The final verdict? Most plans fell woefully short of the requirements of California’s new groundwater management law.

When it came to the impact on drinking water, the results were striking. The San Joaquin Valley’s groundwater plans, as initially submitted – plans that were supposed to help improve our groundwater management – would result in:

- Between roughly 4,000 and 12,000 partially or completely dry drinking water wells by 2040

- Between roughly 46,000 and 127,000 people who lose some or all of their primary water supply by 2040

- Between $88 million to $359 million in costs to replace drinking water in communities that would lose their drinking water supply due to groundwater management proposed by the plan.

Triumphs

Despite the well-documented problems with many of these plans, it remained unclear whether the California Department of Water Resources would pay attention to the red flags raised through the public review process.

Over a year passed.

Then, 12 plans were found to have significant problems and were sent back for improvements.

Many more months passed.

Finally, just this month, the Department officially rejected six plans that failed to address over pumping, stating that the failed plans, “did not analyze and justify continued groundwater level declines and land subsidence…[and] lacked a clear understanding of how the management criteria may cause undesired effects on groundwater users in the basins or critical infrastructure.”

These groundwater agencies are now subject to enforcement actions. David wins a round!

For years residents, communities, and scientists have been routinely shut out of groundwater governance, while millions of dollars have been spent on private consultants to prepare a byzantine set of plans using opaque groundwater models with largely unclear outcomes. Yet, in the end, a scrappy group of scientists and advocates at non-profit organizations were able to triumph against these odds, find the gaps and flaws in the analyses, explain what they meant for the future of drinking water and the environment, and push the state to take decisive action.

Epilogue

Of course, this isn’t quite the end. Indeed, work continues as too many awful plans are being given a barely passing mark by the Department of Water Resources. UCS and our partners, continue to press for better oversight of groundwater management plans that have unacceptable impacts on communities.

A new era is also dawning, one where the State Water Board steps in with the authority and the responsibility to ensure that the wild West of groundwater pumping finally comes to an end. Only when this happens will this truly be a David and Goliath tale.