On Day One of his new administration, President Trump is expected to begin implementing a plan to round up and deport millions of undocumented immigrants. It’s not clear exactly what that will look like, though he has signaled his intent to declare a national emergency, build new detention centers, and use the military to assist deportations—and he has even hinted at deporting legal immigrants and denaturalizing US citizens.

We don’t know whether anyone or anything—the courts, Congress, principled federal employees, or public outcry—will be able to curb the worst of the intended cruelty. But many people will surely suffer, and the hardship likely won’t be limited to immigrants and their families. Because while undocumented (or unauthorized) immigrants work in many sectors in this country, they are especially overrepresented in jobs that are vital to keeping us all fed.

According to the most recent estimates by the Pew Research Center, some 11 million unauthorized immigrants lived in the United States in 2022. About three-quarters of those (8.3 million) were part of the nation’s labor force. The largest numbers of unauthorized immigrants resided in California, Florida, and Texas, where they made up 7%–8% of each state’s workforce. (It’s no coincidence that those three states are major agricultural states employing large numbers of farmworkers.)

Before I get into the ripple effects that mass deportation would have throughout our farm and food system, I must say this: Deporting millions of people for the crime of seeking a better life for themselves and their families in an increasingly dangerous world is morally abhorrent. The plan will likely split up families—after all, Trump aide Stephen Miller, the architect of the first Trump administration’s inhumane policy that separated thousands of children from their immigrant parents, will be at the center of the new deportation push. The administration will almost certainly return people to dangerous and desperate situations in their home countries, or even to countries where they have never lived. And deportations will have negative effects on whole communities.

In addition to being morally repugnant (and impossibly expensive), these plans would be extraordinarily damaging to a food system that relies heavily on immigrant workers, destabilizing local economies and driving up food prices for all of us.

The US food and farm system relies heavily on immigrants

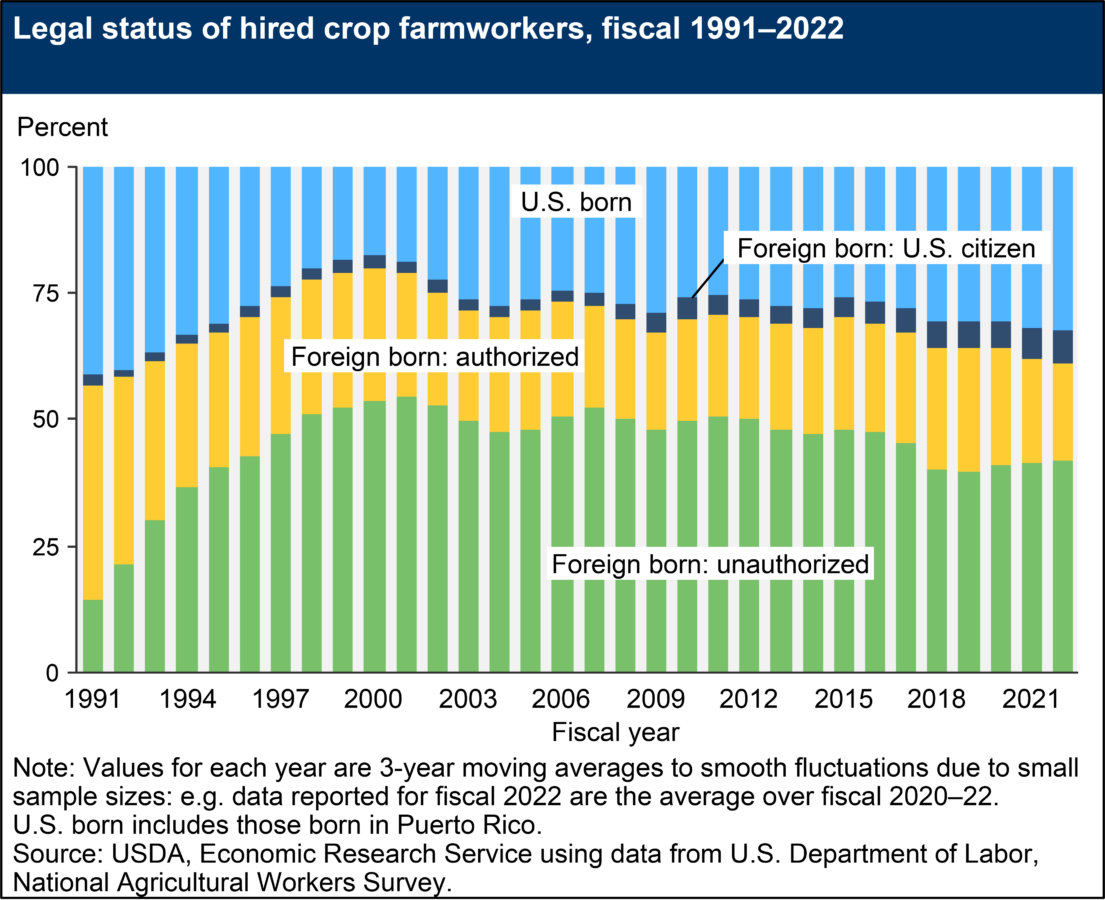

Precise estimates and characterizations of the undocumented population are tricky, for obvious reasons, but we know they make up an outsize share of the food and farm workforce. In 2017, the Pew Research Center estimated that 9% of workers across the US food system, including food production and food processing, were undocumented immigrants. A 2019–2020 Department of Labor survey narrowed in on crop farmworkers and found that nearly half (44%) of the workers interviewed did not have work authorization.

While there are certainly some migrant farmworkers who travel from one location to another following the cycles of various crops, the majority of undocumented workers in the food system are “settled” workers, consistently employed at a single location. This means that in many communities, undocumented workers are neighbors, customers, and important contributors to local economies. But they are rarely treated as such, and in recent months, the Trump campaign ratcheted up anti-immigrant sentiment with its demonizing rhetoric.

Food system workers already face many dangers and injustices

By and large, unauthorized workers in the food system are filling dangerous, dirty jobs that US citizens do not want. Whether documented or not, workers across the US food and farming system are routinely subjected to a litany of hazards. Workers who plant and pick fruits and vegetables face extreme heat—which kills farmworkers every year in Danger Season—coupled with toxic pesticide exposures and wildfire smoke. Dairy workers are at risk of injury from contact with large animals, slipping on wet surfaces in milking parlors, falling into manure pits, and infection with H5N1 avian flu. Workers in large poultry-growing operations similarly face a growing risk of bird flu infection. And workers in meat and poultry processing plants have some of the highest risks of severe occupational injury, including repetitive motion and ergonomic injuries, cuts from knives wielded in close quarters, and exposures to hazardous chemicals.

Communities in which food and farm workers live often have unsafe drinking water polluted with pesticides, nitrogen fertilizer, and manure, as well as other hazards. These workers also perversely face high rates of hunger and food insecurity.

Low wages are the norm for workers in today’s highly consolidated food system, which was built on a long history of exploitation. But for undocumented workers in this system, there is an additional element of fear every day on the job. Because of their tenuous legal status, they are more vulnerable to exploitation and abuse in the form of wage and safety violations, sexual harassment and violence, and more.

Farmworkers and their organizations have been building collective power to expose these injustices and advocate for solutions, and in the last Congress workers and their allies identified 10 bills that would lead to greater dignity and safety. But the incoming Trump administration promises a different future, beginning with the threat of mass deportation. Even if they are not deported, increasing fear in response to violent anti-immigrant rhetoric from Trump and his allies may drive undocumented food system workers underground.

And then what?

The terrifying early days of the COVID-19 pandemic provide the answer to this question.

When food workers are harmed, we all lose

In the spring of 2020, many food workers were deemed essential. While others of us stayed home, supermarket employees, food delivery workers, and food processing workers put themselves at risk of infection, grave illness, and death, every day. In a way, the pandemic merely exposed and exacerbated the hazards and injustices many of these workers already faced. And when these workers got sick with COVID, we saw immediate impacts, especially in meat and poultry plants, which struggled to operate without enough healthy workers.

In 2020, changes in food demand, as restaurants and schools shut down, caused crops to rot in the fields and farmers to dump milk and eggs they couldn’t sell. In 2025, a lack of workers due to actual or threatened deportation could produce eerily similar results. Without enough people to milk the nation’s cows, pick its fruit and vegetables, and process and deliver food, supply chains could break again, wages could spike, and increased costs would almost certainly be passed along to consumers in the form of higher supermarket prices.

It is ironic that a candidate whose team campaigned (albeit fraudulently) on the price of eggs may, in his hateful zeal to rid the country of immigrants, cause a spike in the price of milk. But here we are.