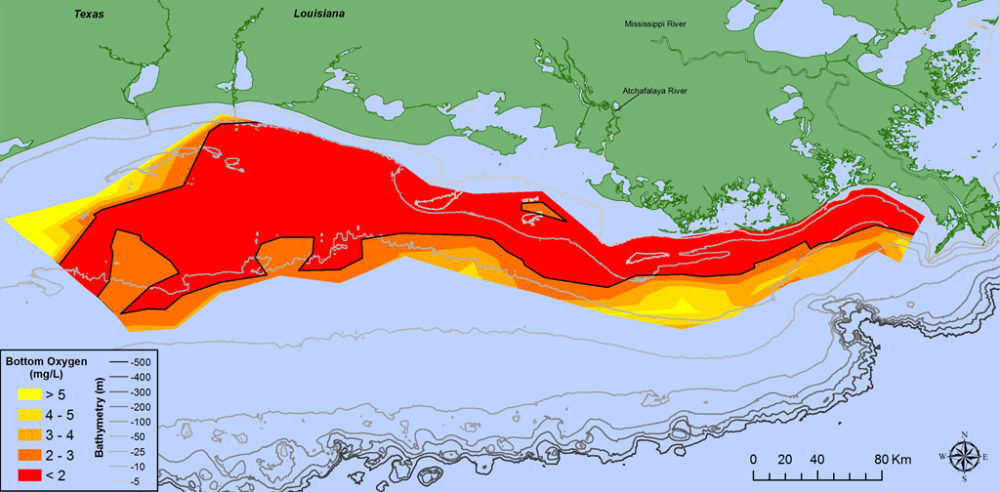

There’s more bad news for the Gulf of Mexico. A team led by researchers at Louisiana State University this week confirmed the largest Gulf dead zone since standardized measurement began in 1985. The lifeless area of low oxygen in the Gulf is now at least the size of New Jersey, the researchers say, noting in a press release that because they couldn’t map the entire affected area, their measurement is an understatement of the problem this year.

As I wrote when it was predicted in June, the dead zone arises each year due to a phenomenon called hypoxia—a state of low dissolved oxygen that occurs when excess pollutants, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, accumulate in bodies of water. These nutrients enter the Gulf largely as runoff from Midwestern farm fields carried by the Mississippi River and its tributaries. They feed blooms of algae that die and decompose, and the process depletes the oxygen in the surrounding water. Fish and other creatures must either flee or suffocate.

We need to reduce farm runoff…a LOT

This year’s dead zone confirmation comes on the heels of a new study last week by scientists at the University of Michigan and Louisiana State University, who looked at what would be needed to decrease the size of the annual Gulf dead zone. Note these researchers aren’t talking about eliminating the dead zone, just shrinking it down…to the size of Delaware. (Delaware! Still an entire state, and not even the smallest one.)

Accomplishing just that, they estimated, would require bold action—a 59-percent reduction in the amount of nitrogen runoff coming from farmland in the Midwestern Corn Belt. That’s a very large reduction, one that farmers almost certainly can’t achieve just through more careful applications of fertilizer. The study’s lead author, University of Michigan aquatic ecologist Don Scavia, was pretty clear about that:

“The bottom line is that we will never reach the Action Plan’s goal of 1,950 square miles until more serious actions are taken to reduce the loss of Midwest fertilizers into the Mississippi River system,” Scavia said.

Instead, the Midwest farming system—which today leaves soil bare and vulnerable to runoff for months out of every year—will need to change.

And speaking of change, our changing climate poses a further challenge to tackling dead zones and related water quality problems in the Gulf and elsewhere. Yet another new study published in Science last week linked toxic algae blooms—a problem also caused by excess nutrient runoff, in which algae by-products can make water unsafe to drink or swim in—to climate change. The authors warned that increased rainfall in future years may wash even more fertilizer into rivers and lakes (e.g., Lake Erie), worsening the problem.

Soil is the solution!

Okay, so we need dramatic reductions in current rates of fertilizer runoff in the Midwest. In recent months, UCS has documented innovative farming practices such as extended crop rotations and perennial prairie plantings that can substantially reduce fertilizer use and runoff. We’ve also shown that such practices and systems are also good for farmers’ bottom lines.

And the evidence that farming practices that keep soil covered year-round can solve multiple problems by reducing rainfall runoff keeps coming. Next week, we’ll release an exciting new report that shows how farmers can create healthier, “spongier” soils, and how Congress and the USDA can help. Stay tuned!