UPDATE: On August 1, scientists at NOAA, Louisiana State University, and the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium released their measurement of the 2024 Gulf of Mexico dead zone. Consistent with their prediction in June, reported in this blog, the dead zone was larger than its annual average, measuring approximately 6,705 square miles, an area roughly the size of New Jersey.

How big will the Gulf of Mexico’s “dead zone” be this summer? I don’t know the answer, but it’s a perennial question this time of year, after spring rains have flushed excess fertilizer from Midwestern farm fields downriver into a warming Gulf, which encourages algae to bloom and then die, sucking oxygen from the water. In June, scientists at the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predicted that this year’s resulting dead zone would be larger than average, covering an area roughly the size of the state of Connecticut. We’ll know in the next week or two if they were right.

In the meantime, I can think of three better questions: Why is there a dead zone in the Gulf anyway? What are policymakers doing about it? And what will it take to actually solve the problem?

Let’s tackle those questions one at a time.

Why is there a dead zone in the Gulf?

The scientific term for what’s going on in the Gulf this summer, and every summer, is eutrophication, a process in which too much nitrogen and phosphorus in a body of water set off a biological chain reaction. This results in hypoxia, a condition in which there is so little oxygen in the water that it can’t support aquatic life. In the Gulf, much of the problem stems from fertilizer runoff from upstream farmland.

A particularly large dead zone in 2024 could be the product of a perfect storm of three trends:

- Excessive fertilizer use – Fertilizer use on US farms tripled between 1960 and 1980 and has remained high ever since. According to the latest Census of Agriculture, commercial fertilizer products were applied on 236.8 million acres of farmland in 2022. But it’s not just that farmers are applying a lot of fertilizer—rather, it’s that they are applying far more than their crops can actually use. Globally, researchers have estimated that only around 35% of the nitrogen fertilizer applied to crops is taken up by the plants it is meant to feed, with the rest being “excess.” The United States is estimated to be responsible for nearly 11% of that excess nitrogen.

- Shortsighted farmland management practices – How crops and soil on farms are managed has a big impact on what happens to all that wasted fertilizer. The predominant practices across much of the US Midwest include growing just a few kinds of crops, with a heavy emphasis on a short-season annual crop (corn). Soil is left bare after the fall harvest, and many farmers, encouraged by Big Ag chemical sellers, apply fertilizer to those bare fields. To make matters worse, a system of underground drainage infrastructure known as “drainage tile,” used across the Mississippi River watershed to prevent waterlogged fields, has the additional effect of funneling unused fertilizer directly into waterways and down to the Gulf.

- Heavier rainfall patterns driven by climate change – Scientists began measuring the dead zone in 1985, and its size has varied with the weather conditions. Years that have featured particularly rainy spring and early summer weather along the Mississippi River have tended to produce the largest dead zones, while dry years see less fertilizer flushed downstream. 2024 has been particularly wet in the Midwest, but climate change is fueling both heavy rainfall and droughts, and we can expect more of this ping-ponging. A 2021 analysis on rainfall patterns and runoff in one Illinois county showed how climate-driven extreme rains wash ever more fertilizer into rivers and ultimately the Gulf.

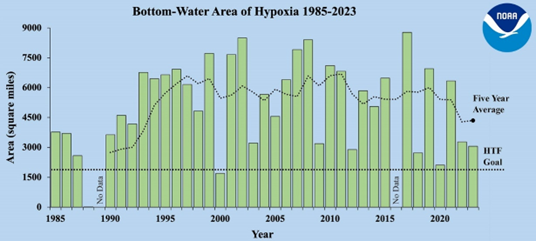

The dead zone in 2023 was smaller than average, but really, what does that even mean anymore? Even an average dead zone—a vast expanse of low-oxygen ocean water that annually reaches the size of a small US state such as Rhode Island (as in 2020), Delaware (2018) or New Jersey (the largest ever recorded in 2017)—is not okay. It’s damaging to the Gulf ecosystem and the people in the region who depend on fishing and seafood for their livelihoods. A 2021 UCS analysis put a price tag on that damage: up to $2.4 billion every year since 1980.

What are policymakers doing about the Gulf dead zone?

The simple answer to that question is: not nearly enough. Government agencies at the federal, state, and tribal levels, led by the US Environmental Protection Agency, came together in 1997 to establish the Mississippi River/Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia Task Force (HTF) with the mission of reducing the effects of hypoxia and the size, severity, and duration of the dead zone. The HTF has set a variety of pollution reduction and water quality goals over the years. But the persistent, infuriating truth is that the HTF and its member agencies are not meeting their own targets.

On the contrary, they are failing badly.

As shown in the graph below, only once in the last 39 years has the Gulf dead zone been measured and found to be smaller than the current goal.

The problem is, governments haven’t taken a level of policy action sufficient to achieve the target outcome. It’s a situation that reminds me of the classic Seinfeld car rental episode: It’s not enough to take the reservation set the pollution reduction goal, you have to hold the reservation meet the pollution reduction goal.

And it’s not just the Gulf that is feeling the effects of persistent fertilizer runoff. This pollution also places a heavy burden on upstream waterways and on drinking water systems across the Midwest, from rural communities in Iowa to cities like Toledo, Ohio.

To be fair, policymakers at the state and federal level have tried some things:

- USDA conservation incentives – My colleagues and I have written for years on this blog about a handful of conservation programs run by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), which offer financial incentives and support for farmers to adopt practices shown to improve soil health, reducing fertilizer use and runoff and generating other benefits. The Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP), for example, is a highly effective program that delivers $4 in returns (including the value of cleaner water) for every dollar invested, according to 2018 UCS analysis. But CSP and other programs aren’t reaching enough farmers to make a dent in the problem, even with the additional dollars Congress invested in these programs in 2022.

- Fertilizer regulations in Minnesota – Minnesota is the rare state that has tried to adopt tough fertilizer regulations to protect water resources, specifically the groundwater that provides drinking water for tens of thousands of Minnesotans. The long and winding road of the state’s Groundwater Protection Rule is chronicled here, but suffice to say that the initial proposal in 2017 ran headlong into opposition by farmers and the collection of agribusiness interests I think of as “Big Ag.” The upshot is that the final rule, which took effect in September 2020, prohibits application of nitrogen fertilizer in the fall and on frozen soils in areas vulnerable to groundwater contamination. But it was watered down and hasn’t been enough to solve the problem that communities are calling a public health crisis. The US Environmental Protection Agency notified Minnesota state agencies in November 2023 that it will intervene if the state doesn’t take stronger action. A few months later, a new bill to tax fertilizer was proposed in the state legislature, but its future is uncertain.

- Crop insurance discounts in Iowa – As a major contributor of nitrogen to the Gulf, Iowa has taken a different tack, encouraging its farmers to take a very specific step—planting cover crops in the off season between crops—to reduce water-polluting runoff. Starting with a pilot program in 2017 and continuing through this year, the state has offered a $5 per acre crop insurance discount to farmers who adopt this soil-covering strategy. The program may well have boosted the use of cover crops in the state: according to the USDA 2022 Census of Agriculture, Iowa farmers reported planting nearly 1.3 million acres of cover crops in 2022, a 33% increase over reported planting in five years earlier. But in a state with nearly 30 million total farm acres, it’s just a drop in the bucket.

At the end of the day, all these interventions haven’t been enoughto solve the problem in the Gulf and other fertilizer pollution hotspots, which we’re reminded of with every summer dead zone measurement.

What will it take to finally solve agriculture’s pollution problem?

After nearly four decades of experience with the Gulf dead zone, it should be clear that we can’t continue to rely on the same policy tools to manage fertilizer pollution and expect a different result. Instead, we should demand a new approach, one that not only helps farmers to shift their practices but also insists that they do so. This could start with addressing the ways that much of the nation’s farm policy, particularly its biggest taxpayer-funded subsidies, actually incentivize pollution.

Take the Federal Crop Insurance Program (FCIP): This program provides taxpayer-subsidized insurance, primarily for large-scale commodity growers, that protects farm income against everything from weather and disaster-related crop losses to crop price fluctuations. But unintentionally, the program also undercuts conservation and soil health by encouraging farmers to plant and produce as much as possible, with little regard for sustainability and resilience. UCS made a case back in 2016 that this perverse incentive is a major driver of fertilizer overuse and other polluting practices. Even the free market advocates at the R Street Institute agree, and their new explainer makes a direct connection between the FCIP—which paid nearly $12 billion in premium subsidies for farmers in 2022—and eutrophication and dead zones.

But what if we could harness the need to insure farms against uncertainty, to both help and push them to farm more sustainably and resiliently?

There’s new support for that idea in one of the unlikeliest of places, the heart of the Corn Belt. In a surprising move in October 2023, the editorial board at the Des Moines Register made a compelling case. Citing the state’s heavily eroded soils and fertilizer-fouled waterways, the editorial board concluded:

Payment of insurance and other subsidies must be connected to farmers doing their work in a way that respects soil and water instead of treating it as a resource to be pillaged.

Whoa.

But the Register wasn’t finished. In June, noting the fact that congressional progress on a new food and farm bill was stalling, the paper issued another editorial under this head-turning banner: “Farm bill needs to be radical, demand more from farmers on conservation.” In it, the paper again pressed the case that farm policy business-as-usual, which it characterized as “ask[ing] for cooperation while dangling cash,” is woefully insufficient. The piece ends with this mic drop:

Taxpayers shell out billions to farmers in the form of crop insurance, which has become so lucrative that it incentivizes bad behavior, such as planting corn on steep slopes. So, granted, crop insurance is far from a perfect vehicle for transforming farm policy to both support farmers and safeguard our soil, water and planet. But the size of the checks issued to farmers makes it an obvious place to start. Plus, tying conservation standards to crop insurance subsidies could serve as both a carrot (paying ultra-generous subsidies to farmers who measurably reduce erosion, as an example) and a stick (making the insurance subsidy awarded for meeting conservation standards so lavish that farmers can’t afford not to reach them).

Drafting precise ways to demand more of the agriculture industry will be exacting and politically difficult work. Democrats and Republicans should get started on it now.

I wholeheartedly agree. Though it might seem radical (to use the Register’s word), it’s not far-fetched to think that with smarter policies, we could have much smaller dead zones to measure in future summers.